L.L. Madrid

Gerald Murnane

“I can say in all honesty and sincerity that I can’t tell the difference between my fiction, my thinking about my fiction, and my life.” Gerald Murnane, who writes his books on typewriters, talks to Ivor Indyk about writing at home in the small town of Goroke in rural southeast Australia. Murnane’s books Border Districts and Stream System: The Collected Short Fiction of Gerald Murnane are both forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux in April.

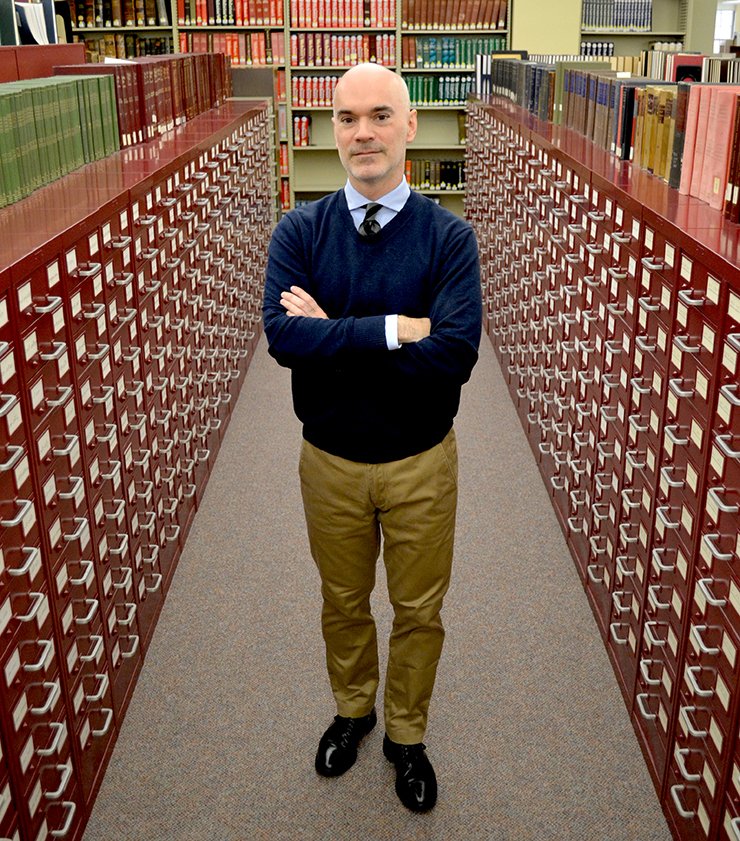

Raymond McDaniel

“If I am too in sync with the present, I can’t write. Or I can write, but I don’t want to, because too great an affinity with the present, of events currently happening, makes me queasy. This isn’t to valorize the past in any way; it’s just an objection to belonging too much to the assumptions of the now. I try to remedy this with strategic alienation. Physical exhaustion helps; I’ll walk twenty miles just to feel a different sort of rhythm, or clean something obsessively. Anything that changes my sense of scale helps: taking macro photos, looking at artifacts that are thousands of years old, thinking about continental drift. Weirdly, this induced estrangement is exactly what I feel when I am compelled by good writing. Recently, it’s what I feel when reading A Separation (Riverhead Books, 2017) by Katie Kitamura, or play dead (Alice James Books, 2016) by francine j. harris, or In the Distance (Coffee House Press, 2017) by Hernan Diaz: the sense that everything but this has fallen away. But I can’t write from the estrangement good writing elicits. I need something material, corporeal, something that either has no mind or has a mind unlike the minds that clutter my daily apprehension of news or media. That difference reminds me that all of this is temporary, and in order to write anything close to what I want to achieve, I need to inhabit that truth.”

—Raymond McDaniel, author of The Cataracts (Coffee House Press, 2018)

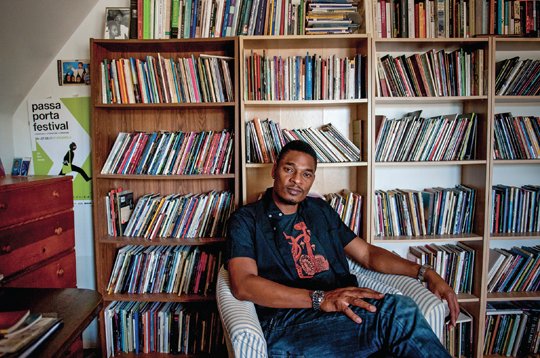

Rudy Francisco

“Most people have no idea that tragedy and silence have the exact same address.” In this video, Rudy Francisco reads his poem “Complainers” from his debut poetry collection, Helium (Button Poetry, 2017), on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon.

Siri Hustvedt on Art and Science

“I think physicists and poets are not as different as we like to think. The same unconscious processes are at work in both.” In this interview from the 2017 Louisiana Literature festival in Denmark, Siri Hustvedt talks about her background in neuroscience, the experiences of writing both nonfiction and fiction, and the value of approaching questions from different interdisciplinary perspectives.

Short Story Essentials: Tapping Into the Power of Scene

Allison Alsup’s short fiction has been published in multiple journals and won multiple awards including those from A Room of Her Own Foundation, New Millennium Writings, Philadelphia Stories, and most recently, the Dana Awards. Her short story “Old Houses” appears in the 2014 O’Henry Prize Stories and has since been included in two textbooks from Bedford/St. Martin’s: Arguing About Literature: A Guide and Reader and Making Literature Matter: An Anthology for Readers and Writers. Alsup received an MFA in Creative Writing from Emerson College, and is the recipient of artist residencies from the Aspen Writers Foundation and the Jentel Foundation. In 2017, she and several colleagues launched the New Orleans Writers Workshop, through which she currently teaches community-based creative writing workshops.

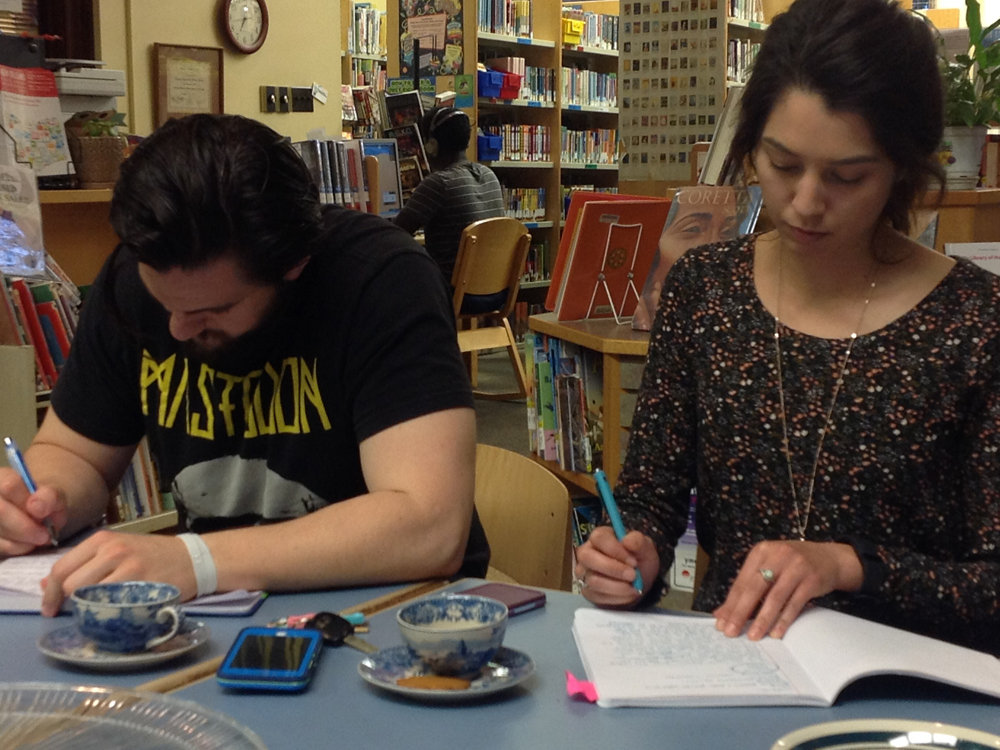

I’ve taught writing for most of my adult life, but community classes, particularly fiction workshops, occupy a special place in my heart. Unlike college classrooms or graduate programs, community classes cast a wide net, attracting a spectrum of writers of all ages, diverse backgrounds and experience. Suddenly a cross section of people that might not otherwise connect gather around a table with a single common purpose: to transform seething, raw images and words into comprehensible, moving stories. Here the CPA rubs shoulders with the waitress, the civil servant with the entrepreneur, only to find that when it comes to the vagaries of the human heart, they have more in common with one another than they might have otherwise thought.

I’ve taught writing for most of my adult life, but community classes, particularly fiction workshops, occupy a special place in my heart. Unlike college classrooms or graduate programs, community classes cast a wide net, attracting a spectrum of writers of all ages, diverse backgrounds and experience. Suddenly a cross section of people that might not otherwise connect gather around a table with a single common purpose: to transform seething, raw images and words into comprehensible, moving stories. Here the CPA rubs shoulders with the waitress, the civil servant with the entrepreneur, only to find that when it comes to the vagaries of the human heart, they have more in common with one another than they might have otherwise thought.

Thanks to a recent grant from Poets & Writers’ Readings & Workshops program, I had the chance to witness firsthand the tremendous material such community classes can generate, even in a limited amount of time. Short Story Essentials met for three Monday evenings at a local public library in New Orleans. Though the class was aimed at adults, the library was designed for children. Despite low tables and tiny chairs, and thanks to a steady supply of ginger snaps and tea from head librarian Linda Gielac, we managed to tackle a pretty big idea when it comes to crafting story: how to write compelling scenes.

Each week, we talked a bit of shop and about technique, but the bulk of our time was spent in heavily guided exercises that began with pre-writing, specifically with take no prisoner questions centering on character, motivation, conflict, and stakes. Together these answers helped to clarify what can stymy even the most advanced of writers: a scene’s given function in the story’s overall arc. What followed was a sustained writing period that alternated between gentle nudging on my part about juggling details around setting, movement, interiority, backstory, and dialogue, and brief periods of silence during which participants scribbled at record speed.

Each week, we talked a bit of shop and about technique, but the bulk of our time was spent in heavily guided exercises that began with pre-writing, specifically with take no prisoner questions centering on character, motivation, conflict, and stakes. Together these answers helped to clarify what can stymy even the most advanced of writers: a scene’s given function in the story’s overall arc. What followed was a sustained writing period that alternated between gentle nudging on my part about juggling details around setting, movement, interiority, backstory, and dialogue, and brief periods of silence during which participants scribbled at record speed.

Great scenes require both conceptual understanding as well as gusto. Between meetings, many writers used their time to their advantage, typing up rough drafts and revising with an eye towards clarifying choices on the page. Sessions were designed to be sequential with each week’s scene building upon the last. As a result, every writer left with a substantial chunk of story, and in some cases, a complete work.

It would be hard for me to exaggerate the importance such a series has on my own writing. I can think of little else that hones my own understanding of scene more than creating, from scratch, an exercise that leads writers from a given premise through its complication to its apex. Nor can I imagine greater inspiration than listening to the plethora of rich storylines that result: a hitherto loyal employee who, due to a chance mistake, ponders a life of embezzlement; a mother who must shatter her teenage daughter’s naïveté about a nefarious uncle; an immigrant cab driver who must confront his past war crimes. Thanks to Poets & Writers, these stories and more are well on their way.

Support for Readings & Workshops in New Orleans is provided by an endowment established with generous contributions from the Poets & Writers Board of Directors and others. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

Photos: (top) Allison Alsup (Credit: Allison Alsup). (bottom) Sean Gremillion and Asha Buehler (Credit: Allison Aslup).How to Write an Autobiographical Novel

“Literature is more of a community effort than most people realize.” Alexander Chee talks about how the essays came together for his first collection, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel: Essays (Mariner Books, 2018), with Rich Fahle of PBS Books at the 2018 AWP Annual Conference & Book Fair in Tampa.

Phenomenal Woman

“Pretty women wonder where my secret lies.” In this SuperSoul Sunday video from 2013, poet, teacher, and activist Maya Angelou recites her inspirational and engaging poem “Phenomenal Woman.”

Samanta Schweblin

Argentinian author Samanta Schweblin talks about living in Berlin and reads from her debut novel, Fever Dream (Riverhead Books, 2017), translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell. Fever Dream, which was shortlisted for the 2017 Man Booker International Prize, was the winner of the 2018 Tournament of Books beating out George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo (Random House, 2017) in the final round.

Diana Arterian

“Like for so many, what otherwise inspired activities that challenge and nourish me have been disrupted by the flood of chaotic daily news. Previously I might lift a volume from my pile of unread poetry, chat to friends about a manuscript, attend a reading—and be revived. While these engagements do inspire, they often don’t provide the same charge. What does revitalize me most, now, is the solitude of a natural space (a garden or trail). When considering why, I think of bell hooks’s ‘Earthbound: On Solid Ground’ in which she writes, ‘Humankind no matter how powerful cannot take away the rights of the earth. Ultimately nature rules.’ And while hooks is making an argument regarding black folks returning to rural spaces to gain experiential recognition that white oppressors have little power in comparison to the earth, while the stakes are different for this reader, while I have always lived in cities—her essay speaks to me. That which provokes my pain or worry is fleeting (as is my life on earth’s timeline), and perhaps I shouldn’t give myself over to suffering’s power as its source has little claim to what sustains us, what will take us. Moving in nature invites me to recognize my smallness in earth’s vast purpose—while simultaneously experiencing wonder in a vine’s reach and twist and leafing. In short: I gain perspective, and tap into feeling. Words often move into the space made there.”

—Diana Arterian, author of Playing Monster :: Seiche (1913 Press, 2017)

Jenny Sadre-Orafai

The Final Portrait

In 1964, the memoirist, novelist, and biographer James Lord sat for a portrait for the artist Alberto Giacometti. The painting session was intended to take only a few hours, but lasted weeks and became the inspiration for Lord’s book A Giacometti Portrait (Doubleday, 1965). In this film adaptation of the book, The Final Portrait, written and directed by Stanley Tucci, Armie Hammer stars as Lord with Geoffrey Rush as Giacometti.

Ramón García

Ramón García, author of the poetry collections The Chronicles (Red Hen Press, 2015) and Other Countries (What Books Press, 2010), reads his poems and speaks with Mariano Zaro for the Poetry.LA series about how his suburban childhood in Modesto, California has influenced his writing.

Between the Starshine and the Clay: Kamilah Aisha Moon at Spelman College

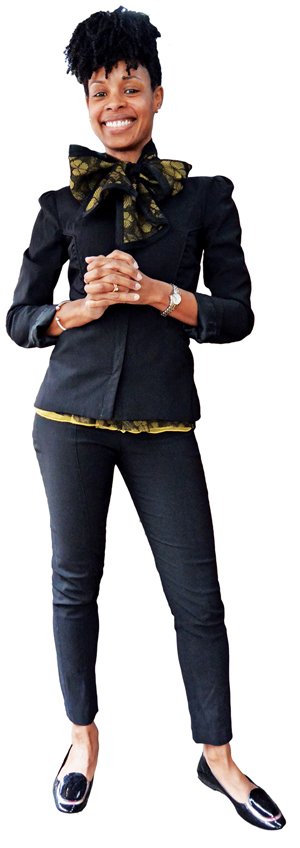

Sarah RudeWalker is a poet and an assistant professor of English at Spelman College specializing in Rhetoric and Composition. Her scholarship focuses on the literature of African American social movements, and she is currently finishing a book manuscript on the rhetoric and poetics of the Black Arts Movement during the 1960s and 1970s. Her creative and scholarly work has appeared in Pluck! The Affrilachian Journal of Arts & Culture, Callaloo, and Composition Studies.

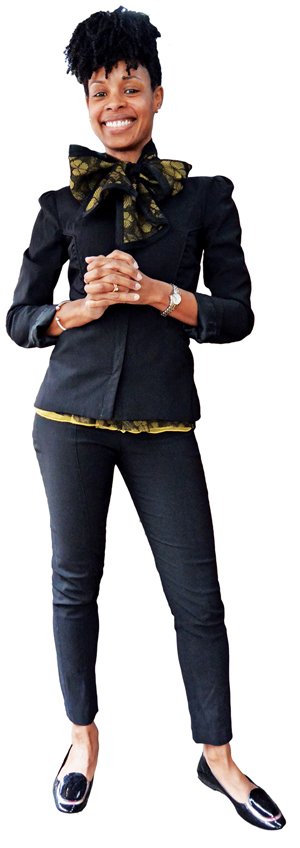

With the renewed support of Poets & Writers this school year, the Department of English at Spelman College has been able to deepen our offerings to the Atlanta University Center (AUC) and West End communities in Atlanta by featuring readings and workshops with brilliant African American women poets. This March, poet Kamilah Aisha Moon kicked off what we call “Lit Week,” a week of events coordinated by Spelman College faculty member and noted poet Sharan Strange and Spelman literary scholar Dr. Michelle Hite. The events aim to highlight the possibilities for art and activism that spin out from the dedicated study of English.

Moon, currently an assistant professor of poetry and creative writing at Agnes Scott College, is a Pushcart Prize winner, Lambda Award finalist, and Cave Canem fellow with two published books of poetry: She Has a Name (Four Way Books, 2013) and Starshine & Clay (Four Way Books, 2017). The Poets & Writers–sponsored events with Moon on March 26 included a craft talk and workshop for student writers, and an evening reading for the community.

Moon, currently an assistant professor of poetry and creative writing at Agnes Scott College, is a Pushcart Prize winner, Lambda Award finalist, and Cave Canem fellow with two published books of poetry: She Has a Name (Four Way Books, 2013) and Starshine & Clay (Four Way Books, 2017). The Poets & Writers–sponsored events with Moon on March 26 included a craft talk and workshop for student writers, and an evening reading for the community.

Moon spent the afternoon talking about craft, inviting students to consider the power of their creative work to “bear witness.” This power, she observed, depends on the writer’s ability to practice craft with attention and empathy. One of the worst things we can do to each other, she observed, is to render someone invisible, and writers, who purposely aim to be “mirrors of treachery and glory,” have the power to do just the opposite: to help us see each other, and especially to see the familiar in a very different way. Moon invited students to interrogate this potential in their own work by presenting her work with disarming vulnerability, sharing early drafts and asking students to critique the choices that led to the final versions of her poems.

The reading that evening was lovingly intimate and set up in Spelman style: Audience members entered to find Moon seated at a candlelit table and listened to a recording of the a capella ensemble Sweet Honey in the Rock as they waited for the reading to begin. Moon opened the reading by noting that although she was never a student at Spelman herself, she fondly remembers the AUC as social stomping grounds for her and her friends. The reading that followed was exemplary of what can happen when the work of a black woman poet is honored within a black women-centered space.

Moon read from Starshine & Clay, whose Lucille Clifton-honoring title is meant to cover a lot of ground—the world of the personal and the public, of the grief and love and joy that exists between the starshine and the clay. Reading her poem “The Emperor’s Deer,” which she first wrote for Michael Brown, she asked the audience to hear it as mourning for the recently murdered Stephon Clark. Reading from the book’s third section, the author asked the audience to acknowledge the ways that personal traumas and historical traumas are intricately connected, to recognize that both the joy and pain of the personal persist while a public trauma blazes and burns. “I never read these,” she admitted, smiling.

We at Spelman commit to continuing to make spaces like these that invite this kind of intimacy between author and audience, especially in ways that honor the work of black women writers. We hope that Kamilah Aisha Moon knows that she has a home here, “on this bridge between / starshine and clay.”

Support for Readings & Workshops in Atlanta is provided by an endowment established with generous contributions from the Poets & Writers Board of Directors and others. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

Photos: (top) Kamilah Aisha Moon (Credit: Sarah RudeWalker). (bottom) Spelman College students with Moon (Credit: Sarah RudeWalker).Anthony Ray Hinton

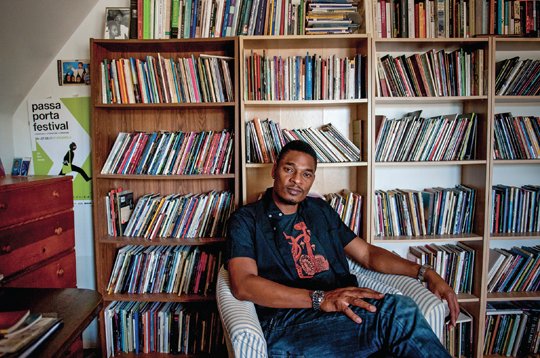

“Reading really saved my life in a way that people probably will never be able to understand.” Anthony Ray Hinton, author of the memoir, The Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row (St. Martin’s Press, 2018), speaks about starting the only known book club on death row and the power of reading.

Two More Weeks to Submit! The Question of Extended Deadlines

You’ve just finished polishing your story, essay, or poem. The contest deadline is just a few days away. You’ve reread the guidelines and double-checked your manuscript to make sure you’ve followed them perfectly. After paying the twenty-five-dollar entry fee, you click Submit and feel the familiar rush of accomplishment, nervousness, and hope. The long submission period will close; the even longer wait for results will begin.

But no sooner have you joined the magazine’s mailing list than you receive an e-mail from the editors: “Good news!” the message begins, followed by a gleeful announcement that the deadline has been extended. “Two more weeks to submit! So get those submissions in!” Perhaps you don’t share the editors’ enthusiasm. Maybe you even feel a little burned. You begin to second-guess your decision to not work on that other, longer story, the one you were excited about but likely would have taken until midnight of the (original) deadline day to get into shape. You followed every guideline; you played by the rules, as you always do. You did the work, submitted your best writing, and were prepared to accept your losses. In a moment of cynicism you wonder if the deadline was extended for that extra few hundred dollars in entry fees the magazine will surely receive, widening the applicant pool and, as a result, making it harder for you to win. “If the contest itself doesn’t stick to its own assigned deadline,” you think, “why should I?”

Admittedly, the above scenario had never occurred to me, a writer who oscillates between abject inattention and extension zeal. An extra week, you say? Great! Now I can definitely submit! Sometimes I’ll capitalize on the almost-missed opportunity. Most times, as the extended deadline comes and goes without my submission, I gather those ribbonless poems to submit to an open reading period instead. But to writer and visual artist David Colosi, the practice of deadline extensions is a thorny issue. In a letter to the editor, printed in the January/February 2018 issue of this magazine and appropriately titled “Rejecting Extensions,” Colosi asked a simple question: “Why do writing contests extend their deadlines?” Were too few submissions received? Was the quality or diversity of the submissions subpar? Did the publication fall short of its financial goals? Did the editors just want to make more money? With seemingly more and more contests extending deadlines, typically without explanation, writers like Colosi are left to speculate.

Whatever the reason a sponsor might extend a deadline—whether for a contest, a reading period, or a fellowship—one can hardly imagine a room full of suited, greedy editors or administrators laughing raucously as the twenty-five-dollar fees roll in. The reality is that no one in their right mind goes into small-press publishing or nonprofit administration for financial gain; most publications operate on budgets incommensurate with the vital work they do to support writers, and nonprofits are, well, not profiting by serving a mission rather than a bottom line. Still, the lack of transparency that often accompanies deadline extensions can leave the motivations of a contest sponsor up to the writer’s imagination. “They wrote the rules, so they should stick to them,” wrote Colosi in his letter. “If I had any power in saying so, I would reject their extensions. If a publication fails to get enough submissions, money, or variety, it should accept its own failures.”

To better understand the rationale behind deadline extensions, I contacted more than a dozen editors and prize administrators whose contest deadlines were recently extended. My inbox was not exactly flooded with responses. After my initial requests, and a round of follow-up e-mails, I began to feel like a literary Typhoid Mary, deliberately ignored or politely turned away because of what I was told were busy editorial schedules. “I think from our perspective, a little mystery is not a bad thing,” added one editor who declined an interview.

“There are two sides to it,” says Ander Monson, editor and publisher of DIAGRAM, which sponsors a yearly chapbook contest. “One wants the contest to be robust so it makes sense financially for the press, which also makes it feasible to run and award the prize to the winner, and extending a deadline occasionally may help with that. The flip side is that it might be read by some as not fair to those who did the work to get their manuscripts in by the original deadline, at the expense of whatever other obligations in their lives. This is why DIAGRAM won’t accept late entries, for instance.”

Jen Benka, executive director of the Academy of American Poets, similarly remarks on the possible benefits and drawbacks of extensions and how better administrative practices might produce better outcomes. “In the past the Academy of American Poets has extended the submission deadlines of some of our prizes to ensure that as healthy a number of applications as possible were received,” she says. “We’ve stopped doing that, though, in fairness to the poets who worked hard to meet the original deadline posted. Instead we’ve learned to pay closer attention to the pace at which submissions come in—knowing that the vast majority almost always arrive on the last day—and to work harder to promote the upcoming deadline.”

In responding to Colosi’s letter, Poets & Writers Magazine editor in chief Kevin Larimer reminded readers that not all presses and magazines make money on contests (see “101 Free Contests” on page 48), and indeed, the cost of running a contest often extends far beyond paying winners to include the judges’ fees, readers’ fees, advertising, marketing and promotion, and so on.

Poets & Writers, Inc., the nonprofit organization that publishes this magazine, sponsors two annual writing contests that invite submissions: the Amy Award, for women poets under the age of thirty, and the Writers Exchange (WEX) Award, which offers emerging poets and fiction writers a trip to New York City to meet with publishing professionals and to give a reading. The deadlines for both contests, neither of which charges an entry fee, have been extended in the past. “When we’ve done this, it has been based on only the number of submissions received, not their quality,” says Poets & Writers executive director Elliot Figman, noting that submissions are not read until the application window is closed. “Particularly with the WEX Award, which each year invites writers from a different state to apply, reaching interested writers can sometimes be challenging. We may have to get more familiar with the chosen state’s literary community in order to identify which organizations or platforms can help us get the word out to eligible writers. Moreover, because most submissions come in really close to the deadline, it can be hard to gauge whether or not our outreach was effective until just before the announced deadline. If the number of applications is significantly lower than in prior years, we have sometimes wanted to do another round of outreach. We don’t have anything to gain by extending a deadline; rather, we want to be sure that as many eligible writers as possible have an opportunity to participate.”

Similarly, contests that attract a large international audience can face unexpected delays that require short deadline extensions. Donald Singer, cofounder of the U.K.–based Hippocrates Initiative for Poetry and Medicine (which sponsors a £1,000 poetry prize with a £7 entry fee) explains the challenges of managing an international competition. “We have entries from around the world—from thirty-seven countries this year alone—and from over sixty countries since the prize was launched. We have often extended our deadline for a few days. Our preferred method of submission is online, and many participants enter very close to the deadline; a short extension allows the minority of entrants who may have technical problems to resolve such issues. It also allows entrants from less developed countries—where infrastructure problems may lead to delays in making a planned entry—more opportunity to enter.”

Late last year the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Massachusetts, for the first time in the history of its residency program, extended the deadline for its fellowship competition, which has a $50 application fee, by two days. “Traditionally our deadline for writing fellowship applications is December 1,” says Sophia Starmack, the program’s writing coordinator. “This year December 1 fell on a Friday. We thought that it would help our applicants to have the cushion of the weekend to finish preparing their samples. Most emerging writers are juggling day jobs, gigging, classes, and multiple projects. We [thought we] could offer a few extra days when writers might have a little more breathing room to prepare or finalize their applications.”

Meanwhile, Ricardo Maldonado, a poet and translator and the managing director of the 92nd Street Y’s Unterberg Poetry Center in Manhattan, which sponsors the annual Discovery/Boston Review Poetry Contest (a prize that includes $500, publication, and a two-night residency at the Ace Hotel in New York City and has a $15 entry fee), will consider an extension of a day or two for writers who encounter a problem meeting the deadline and request extra time. Rather than extend the deadline, he instead allows for a small window of leniency at the end of each entry period. “I frequently juggle deadlines and other commitments,” Maldonado says. “I have to administer prizes with the understanding that applicants might seek an extension after having tried to meet requirements by a set time and are unable to because of extenuating circumstances. In general a deadline of Friday at 5 PM perhaps means Saturday evening or Monday.”

“As for my own experience as a writer,” he adds, “an extension means an extra chance to dot the i’s, an extra hour or so to think about what I want to say.”

The vast majority of writers will likely agree that the occasional extension is understandable, and excusable—and, indeed, most of the writers I spoke with while writing this story had, like me, never really considered the issue and had little or no problem with it; several assumed that writers who do take issue are, simply put, those who might be looking for someone to blame when they don’t win. But once extensions become a regular occurrence, a certain degree of skepticism is only natural. “The occasional deadline extension can be beneficial to all parties,” Monson says, “but it can also be an indication of an underlying issue. It’s okay to extend a deadline one year, but if you do it the next year, too, then something [may be] wrong structurally with your contest or the way it’s managed or publicized.”

Hunger Mountain, which like many publications relies on revenue from contests to cover operating expenses (paying writers, printing costs, and so on), extended the most recent deadline for its contest series in poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and young adult and children’s writing, each charging a twenty-dollar entry fee—from March 1 to March 15. “We are a very small, dedicated staff,” says editor Miciah Gault. “We were late announcing our judges for the contest this year, so we thought it was only fair to extend the contest deadline once we’d finally announced those names. We have to leave enough time after announcing the judges to get a ton of entrants, so we know—and our readers know—that the winners really deserve that honor. This year, since the AWP conference fell in early March, we also felt that a March 1 deadline would be a missed opportunity for broadening our range of submissions.” Last year Hunger Mountain extended its contest deadline for the same reason, a late judges announcement, but only by one week. In both years the contest opened for entries on October 1 of the previous year, allowing for a five-month window for submissions.

“It’s not that we’re looking for any particular number of entries,” Gault says, “but if we see that the number is significantly lower than in previous years, we assume that we’ve done a poor job of promoting the prize, and we extend the deadline to redouble our efforts to promote.”

While it’s true that deadline extensions may benefit writers who missed the original entry period, for Colosi, who holds an MFA from the California Institute of the Arts and has received awards for his visual artwork, the contest sponsors are ultimately the ones who win. “A deadline sets the terms that everyone agrees to play by,” he says. “When editors extend it, the advantage is only theirs and, I suppose, that of the late submitters. The punctual submitters lose. Just as my overlooking a typo or forgetting the word count or using Arial instead of Times New Roman would be a sign that I wasn’t organized or didn’t read the directions, so too does the sponsor appear disorganized when they extend the deadline. They can disqualify me for my error, but I can’t disqualify them for changing the terms.”

Jeffrey Lependorf, executive director of the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses (CLMP), the organization responsible for creating the CLMP Code of Ethics in 2005, defends the practice of extending deadlines. “Deadlines are extended routinely to allow greater participation,” he says. “I don’t think it’s unethical. If a deadline was extended many times over a long period, then one might question the ethics. I think writers should see this as a benefit. If it seems unfair, then I have to question the writer. Why is it unfair? Because the pool is larger? One has to believe in one’s own work. Whoever else applied doesn’t matter. As long as a work is awarded, and as long as guidelines are held to, then there’s nothing unethical about extending a deadline. I would see it as a gift to those who missed the deadline.”

The question then is whether contest sponsors have an obligation to be more transparent about the possibility that a deadline may be extended. After all, CLMP’s Code of Ethics states, in part, “We believe that intent to act ethically, clarity of guidelines, and transparency of process form the foundation of an ethical contest.” Disclaimers of the sponsors’ right to extend deadlines, however, are notably absent from the majority of contests’ fine print. “Ideally a publisher might state as part of their guidelines that they reserve the right to extend the deadline,” says Lependorf. “Greater transparency should always be a goal of contest guidelines. Ultimately the greatest beneficiaries of a contest should be writers, and writers should be provided with clear and appropriate information to allow them to make a reasoned, informed decision about participating or not.”

In the end it’s unlikely such measures would change the minds of writers like Colosi. “The bottom line is that when a deadline is extended, it increases my chances of losing,” he says. “And my goal in following all of the requirements is to increase my chances of winning.” To contest sponsors considering a deadline extension, Colosi offers this advice: “Take what you have and find the magic in it. Fix the problem next year. Until then, embrace a new winner that you probably never would have seen in a bigger crowd.”

Editor’s note: Let us know what you think. Are deadline extensions just a natural part of writing contests and this issue much ado about nothing? Or should sponsors stick to the deadline, just as they ask entrants to do? At the very least, should sponsors be more transparent about their reasons for extending a deadline? Send an e-mail to editor@pw.org and share your opinion.

Maya Popa is a writer and teacher living in New York City. She is the author of the poetry chapbooks The Bees Have Been Canceled (New Michigan Press, 2017) and You Always Wished the Animals Would Leave (New Michigan Press, 2018). Her website is www.mayacpopa.com.

Anatomy of Awards: March/April 2018

This issue’s Deadlines section lists a total of 118 contests sponsored by 78 organizations, offering a total of 130 opportunities for writers and translators to win an estimated $617,810 in prize money. This is roughly 26 percent more money than was offered a year ago, in the March/April 2017 issue, when this section listed 121 contests sponsored by 81 organizations, offering a total of 135 opportunities to win an estimated $489,910.

Tracking Submission Managers

While writers once spent precious time and effort at the post office mailing poems and stories to journals and presses, over the past decade submission managers have helped make the process faster and easier. Nearly gone are the days of the SASE, of sorting through dozens of publishers’ submission guidelines and enduring long periods of radio silence; instead, writers can now simply log in to a submission manager and instantly check the status of their submissions and learn of upcoming deadlines. And the landscape continues to change: Stalwarts like Submittable and the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses’ Submission Manager—both designed to help publishers and organizations manage the submissions they receive—have been running strong for years, while new platforms continue to emerge, shifting their models to focus more specifically on the needs of the modern writer.

One such platform is Literistic, a service launched last June that helps writers manage their submissions by identifying opportunities that match their publishing goals. Subscribers indicate their preferences—what genre they write, if compensation is a priority, whether they’re willing to pay reading fees—and receive a monthly e-mail that lists upcoming deadlines for literary journals, contests, grants, and fellowships tailored to those preferences. Literistic’s cofounders, Liam Sarsfield and Jessie Jones, both writers in Vancouver, hope to help fellow writers face what can seem like an intimidating number of opportunities. “In my own experience, just getting my head around the work I have to do is often difficult,” says Sarsfield. “Something as simple as being gently reminded to do it regularly is hugely valuable.”

Literistic is ad-free, but charges subscribers a few dollars per month or about forty dollars a year. Sarsfield hopes to make the customized monthly e-mail writers receive even more specific in the coming months. The service also offers a free “shortlist,” which provides forty to seventy non-customized monthly deadlines, each vetted by Sarsfield and Jones. Literistic follows the lead of Duotrope, which since 2005 has also helped writers find and keep track of places to submit, with a curated database of contests and journals, a calendar of upcoming deadlines, and a built-in submission tracker.

While Literistic is just getting started in the submission management market, one of the first such platforms, Tell It Slant, folded in August of last year. Established in 2009 by writer Jenn Scheck-Kahn, her husband, and a few friends, Tell It Slant managed the logistical and technical side of submissions for a variety of literary journals. One popular feature allowed writers to submit simultaneously; if one journal accepted a piece, that submission disappeared from the queues of other journals. A few years after the site’s launch, Scheck-Kahn and partners also launched Journal of the Month, a service that regularly mails out a different journal to subscribers throughout the year. The time commitment necessary to manage both projects, however, became too much. “We were managing two different businesses, and started to have children and families,” says Scheck-Kahn. At the same time, Submittable—founded in 2009 by three developers in Montana—started to take off, providing some of the same services to writers as Tell It Slant. Scheck-Kahn and crew reevaluated their priorities as literary advocates and decided to concentrate their energies on Journal of the Month. Since then, Submittable has gone on to become one of the leading submission managers, having been adopted by roughly nine thousand journals, presses, and organizations.

While submission managers and services like Literistic are certainly appealing, Scheck-Kahn is concerned that their growing ubiquity may risk excluding writers who lack access to the Internet, such as prison inmates, writers who live in remote regions, or those who simply choose not to use it. “I wonder if there’s a natural filter in place because we allow electronic submissions,” she says, noting that she encourages magazine editors to accept paper submissions in addition to electronic ones. (A few holdouts, such as the Paris Review and Zoetrope, still only accept submissions by postal mail.) In the end, though, Scheck-Kahn believes that facilitating the submission process for writers is ultimately a positive thing. “It’s great having better accountability,” she says. “Writers are able to get their work out there with fewer barriers.”

Rachael Hanel is the author of We’ll Be the Last Ones to Let You Down: Memoir of a Gravedigger’s Daughter (University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

Reviewers & Critics: Laila Lalami of the Nation

Laila Lalami is well known for her extraordinary fiction; she is the author of the novels Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits (Algonquin Books, 2005), Secret Son (Algonquin Books, 2009), and The Moor’s Account (Pantheon, 2014), the most recent of which appeared on the longlist for the 2015 Man Booker Prize and was named a finalist for that year’s Pulitzer Prize. But she is equally well known for her sagacious literary criticism and writings on politics and culture. Over the past thirteen years she has written book reviews for a wide array of outlets, including the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, and the Boston Globe. Lalami reviewed fiction and nonfiction for the Nation from 2005 to 2016, at which point she started writing the Between the Lines column for the magazine. Since 2016 she’s also been a critic-at-large—along with nine other writers, including Alexander Chee, Marlon James, and Viet Thanh Nguyen—for the Los Angeles Times, where she writes mostly about the literary life. Lalami, who was born in Rabat, Morocco, and educated there as well as in Great Britain and the United States, is likewise highly regarded because of her popular literary blog, Moorish Girl, which she launched in 2001 and, after the publication of Secret Son, folded into her website, lailalalami.com. She currently teaches creative writing at the University of California in Riverside. You can follow her on Twitter, @LailaLalami.

You got your start writing for the Oregonian in 2005, reviewing books by Reza Aslan, Luis Alberto Urrea, Salman Rushdie, and Zadie Smith. What path led you to literary criticism, and how did that relationship with the Oregonian begin?

At the time I had just moved to Portland from Los Angeles and was working on my first collection of short stories. It was a lonely time in my life—I knew perhaps two or three people in the entire city—so the book section of the Oregonian became a kind of conversation I missed having about books. I also had a literary blog where I wrote about stories or novels I was reading, and that helped me broaden my reading interests. I think I was drawn to criticism because it gave me an opportunity to articulate what I thought about a piece of writing—what it tried to do, whether it succeeded, and, if so, how it succeeded. But the only way to find out if I could do it was to give it a try. So I wrote to Jeff Baker, who was the book review editor for the Oregonian, and asked if he might be interested in having me write about a book I’d just finished. It was slated to be published the following month, so it was already assigned, but he looked up some of my writing on the blog and asked me if I was interested in Luis Alberto Urrea’s The Hummingbird’s Daughter. Before that review came out we were already talking about doing a piece on Reza Aslan’s No god but God. Some weeks later Adam Shatz, who at that time was the literary editor of the Nation, asked me if I would be interested in reviewing for the magazine. This gave me the opportunity to write longer pieces on the work of Tahar Ben Jelloun, J. M. Coetzee, Joan Scott, and Percival Everett, among many others.

You’ve also published many essays and opinion pieces over the years—including multiple pieces for the New York Times Magazine, the Nation, and the Los Angeles Times. How does your literary criticism inform your political and cultural analysis, and vice versa?

When I write literary criticism, I try to be open to the premise of the work, to discover what the intention was, and whether that intention was fulfilled in the text. I examine the choices that have been made, in terms of characterization or point of view or tone, and whether these choices were effective. I think of it as a journey of exploration into another writer’s mind. But the essays I’ve been writing for the New York Times Magazine involve turning the appraising gaze inward. Often I use my own experiences to explain or inform how I view a particular subject, whether it be the building of a wall along the border with Mexico or the Trump administration’s executive order on immigration. I’m also now a columnist for the Nation, and that of course means building an argument while also advocating for a particular position or a given policy. But what all these forms of writing have in common, for me, is the imperative to place the subject within a very clear context for the reader and to be intellectually honest about it.

What sorts of things influence you when deciding whether or not to review a book?

Three things: time, contribution, ethics. I have to balance my writing and my teaching with all of my other commitments, so typically the first question for me is whether I have the time to read and think about the book thoroughly. The second question I ask myself is whether I have anything useful to contribute to the conversation about it. Would I be a good reader for this particular book? And the third question is: Can I be fair about it? I don’t do reviews if there’s an ethical conflict with the author, if we’re friends or colleagues.

You review both fiction and nonfiction. Do you have a preference for one over the other?

No. I really enjoy doing both because they’re so different and make me grow as a reader and as a person. When I review nonfiction I tend to do a lot of background research, which takes up a lot of time. With fiction I don’t need to do much research for the review, but I usually end up reading related things, like other books by the same writer.

Do you have a favorite book review you’ve written?

That is a tough question! I enjoyed writing about Salman Rushie’s memoir Joseph Anton for the Nation. The review I heard the most about from readers—and still do, ten years later!—was a piece I did on Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Irshad Manji’s books, also for the Nation.

When you’re reviewing a new book from an author with previous books to his or her name, do you read the author’s backlist as well?

Oh yes. This is what I meant earlier when I said that I try to place the book in a clear context. I take note of the book’s literary antecedents, by which I mean works that might have informed it or influenced it. I also read the author’s previous books, to see how they might relate to the one under consideration.

You’ve reviewed graphic memoirs by Alison Bechdel, Marjane Satrapi, and Riad Sattouf. Can you reflect on the differences between reviewing this increasingly popular literary genre—work that is just as much visual as textual—and work that is entirely textual?

Comic books and graphic novels were a huge part of my life when I was growing up, so I’ve always had a soft spot for them. My husband has a significant comic book collection, so they’re always around the house. Still, I fear I am more limited in this genre because I don’t have visual arts training, and I try not to take on an assignment unless I’m really drawn to the subject matter.

Having published three works of fiction, you must know well the hopes and anxieties authors have about book reviews. How does it feel to be operating from the other side, as a critic?

It’s not easy. But I also know that the act of reading is by its nature biased: Each reader brings his or her own literary background and personal experiences to the act of interpretation. When I work on a review I try to keep in mind that my first responsibility is to readers: It’s my job to tell them about the book, what it has to say about the world, and how well I think it does this.

The literary industry and the literary media landscape have changed considerably since you began publishing. The detrimental effects are well chronicled; are there any changes you’ve noticed that you find positive?

It seems to me the entire landscape changes every five years. But I think one positive development is that the barriers for entry are a lot smaller now than they used to be. The literary conversation takes place mostly online, but anyone can set up social media accounts and instantly connect to other readers, writers, and critics. It’s never been easier to research agents or literary magazines or story contests than at the present moment. Unfortunately this hasn’t had much of an impact yet on the well-documented inequities in the publishing business. We need change there, too.

If you could change one thing about the book-reviewing process or the world of book criticism, what would it be?

I would love to see more effort and rigor in criticism of books by writers of color. There is a tendency, among certain critics, to treat writing by white writers as literature and writing by writers of color as ethnology. A lot of space is devoted to the scrupulous tallying of cultural detail and relatively little to literary choices made by the writer. I also wish that American critics would try to read a bit more world literature and literature in translation.

You’re active and quite popular on social media. How useful do you find it as a critic and as a writer?

As a writer I’ve found it to be a disturbingly effective procrastination tool. Never is the temptation to tweet stronger for me than when I’m on my second cup of coffee and it’s time to start working on my manuscript. A few years ago I bought software that blocks the Internet for up to eight hours, and I really don’t know what I would do without it. As a critic, though, I think social media can be quite dangerous. A place with so many opinions makes it hard to maintain independent thinking.

Which book critics, past or present, do you particularly admire?

So many. I came across the work of Edward Said and Chinua Achebe when I was in graduate school, and their criticism was at once a revelation and an inspiration for me. I’ve also learned a lot from Ngugı wa Thiong’o and James Baldwin. I still return to Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark because she’s so incredibly perceptive. Among the younger critics, I often read Parul Sehgal, Michael Gorra, and Pankaj Mishra.

What books that you aren’t reviewing are you most looking forward to reading in the near future?

I’m really excited about Zadie Smith’s new collection of essays, Feel Free. I really loved her previous book of essays. In fiction I’m looking forward to Denis Johnson’s The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, Tayari Jones’s An American Marriage, and Lauren Groff’s Florida.

Michael Taeckens has worked in the publishing business since 1995. He is a cofounder of Broadside: Expert Literary PR (broadsidepr.com).

Reviewers & Critics: Leigh Haber of O, the Oprah Magazine

Leigh Haber is the books editor at O, the Oprah Magazine, a position she has held for more than five years. She graduated from George Washington University with a degree in international affairs, and after getting a job as a copy aide at the Washington Post Book World, she worked for many years in book publishing, first in publicity and later as an editor—at Jeremy Tarcher, Ballantine Books, Avon, Bantam Books, Berkley Books, Harcourt Brace, Scribner, Hyperion, and Rodale—before turning to work as a freelance editor and start-up consultant. At O, the Oprah Magazine, Haber is responsible for putting together the Reading Room section of the magazine, and is always on the lookout for books to feature or excerpt elsewhere in the magazine. She also works with Oprah Winfrey and the rest of the staff to identify new candidates for Oprah’s Book Club. She can be followed on Twitter, @leighhaber.

You got your start in the literary world as a copy aide at the Washington Post Book World in the late 1970s. What was it like working there? Did it make you want to forge a path within the publishing world?

I arrived there not realizing there was an industry behind the books I loved reading—I’d never thought about it before. It was soon after Watergate, so the Post was a glamorous and iconic place, filled with characters. My first boss there was William McPherson, who’d just won the Pulitzer for criticism. He passed away last year, sadly, but that was a universe I am lucky to have glimpsed up close, and, yes, it did lead me to publishing.

You later worked in publicity for several years at Ballantine and Avon, and after that, in editorial for many years at Scribner, Hyperion, and Rodale and as a freelancer. How does your former experience as a publicist and editor inform your role today?

I am so steeped in the book world—it helps me stay on top of what’s coming out when, especially given that we work so far in advance, when there are no indicators of the reception a book will receive. Many of my book publishing colleagues—authors, editors, publishers, agents, publicists, media colleagues—I’ve known them for decades, which helps inform everything I do at O. But I like to try to approach the job itself as a reader, plain and simple. Do I love the book? Will our readers? And are we helping them to discover new talent or writers they’ve never read before, especially women writers? Are we finding books that will challenge or delight them? That’s our mission.

Who are some of the notable authors you worked with—and what are some notable projects you worked on—before you started at O?

When I was a publicity director I flew all over the place with a range of authors I now realize is absolutely astonishing, though at the time, being a mother of two boys, I was just trying to keep it all together. I worked with Alice Walker, Gloria Naylor, Umberto Eco, Charles Simic—and also Jimmy Buffett and Helen Hayes, to name a few who really stand out. I also worked on a tour with Mickey Mantle, which thrilled my dad. At Avon Books they were publishing lots of writers who were just gaining a literary reputation, including James Ellroy, Elmore Leonard, and John Edgar Wideman. But there I also worked with Rosemary Rogers. Those were incredibly fun days.

As an editor, I’m probably proudest of having acquired and edited Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth. But there are so many other writers I am honored to have worked with: Steve Martin, Jacqueline Novogratz, Jonathan Ames, Richard Hell, Tess Gallagher, Lou Reed, Glen David Gold, the Kitchen Sisters, Terry Gross, Bill Maher, the authors of The Intellectual Devotional, Scott Simon, Aasif Mandvi, Peter Jennings…

The literary coverage at O is quite expansive and varied. You oversee book reviews, book lists, excerpts, and original essays—anything else? How has your job evolved over the five years you’ve been there?

When I walked into this job more than five years ago, I’d never been a magazine editor. I didn’t know what I didn’t know, but my editors did. From them I’ve learned an entirely new skill. And I’m still learning. On the first day of my job I was told I needed to send some books to Oprah for book club consideration. I was frankly terrified. But then I read Twelve Tribes of Hattie by Ayana Mathis and I just felt it was a book Oprah would embrace. We’ve had six picks since then, and it’s always a thrill to know we are helping the authors to grow their audiences. Oprah’s passion for books is at the core of my job and always at the top of my mind. I consider it a privilege to assist her in bringing an entirely new dimension to a writer’s career. As far as Reading Room is concerned, I love that the support is there to be feminist, to be globalist, to be diverse, to cover poetry and literary fiction and emerging writers along with the established. And, yes, now I’m also helping to find essayists and contributors to the themed packages we do. How has it evolved? I will always recall this position as one that has to be occupied with a weird combination of humility and a kind of hubris. As to the hubris, I have to choose a few books to cover from the many worthy candidates, which means I have to trust my taste. Humility because I am always aware how lucky I am to be working on this platform, as a part of the incredible legacy Oprah has earned.

Walk me through what a typical week in the office is like for you.

We receive hundreds of books per week—probably two hundred a day. Sometimes it feels as if every day is Christmas, and other days I feel as if I’m drowning in books. And some of the books we receive make me wonder—is there really an audience for a topic this narrow and obscure? But every day I’m combing through the mail, opening packages, and trying to get a sense of the landscape. Most of the time my eyes are bigger than my stomach, and I bring home a bag bursting with books—I still read from the physical galleys. I have a beanbag chair in my office, and there are days when I am sitting in it, looking from my window overlooking Central Park from the 36th floor of the Hearst Building and thinking, “They’re paying me to read?”

I love envisioning the section every month with my editors and my partner in the art department, Jill Armus. There’s a lot of back-and-forth in terms of finding contributing writers, editing, revising, fitting, fact-checking, and so on. My favorite moment is when I see the section come together on page. The hardest times are when I’m working on the mammoth July Summer Reading package—eighteen pages instead of four. It’s tough trying to do something different and to get it right, but it’s exciting, too.

But it’s not all about books. We have a lot of conversations about a wide range of topics. Gayle King’s assistant is obsessed with Beyoncé. I’ve had to learn about her. You pretty much can’t survive in the O office without being a passionate pet lover, whether dogs or cats. You have to be willing to discuss your sex life, your therapist, how long you wear your favorite bra before washing it. It’s all fair game.

How many books do you typically receive per week—and of those, how many are you able to write about each month?

I would estimate we receive five hundred to seven hundred books a week. Of those, we can typically cover about fifteen a month.

Other than your interest in a particular author, what sorts of things, if any, influence you when choosing which titles to include—blurbs, prepub reviews, large advances, social media buzz? What about your relationships with publicists and editors—do those ever hold any sway?

I don’t view blurbs as helpful. They seem very quid pro quo to me. Raves in prepubs do sometimes alert me to books I need to take seriously. Advances don’t matter to me, and while I very much value my relationships with publicists, editors, and authors, it’s all about the read.

How conscientious are you about diversity—gender, race, sexual orientation, etcetera—when choosing what to include? And do you try to pay attention to books published outside of the Big Five publishers?

When I first started at O, I made a conscious effort to make the section and its contributors “diverse.” But I have to say that now happens organically. And all things being equal, if there’s a choice between a great book by a man and a great book by a woman, the woman wins.

O has been particularly inclusive of poetry over the years. Is poetry a special love of yours? Has it ever been difficult persuading editors to allow space for it?

I am not a poetry maven. I admire it, and I love reading it at times, but I don’t consider myself an expert by any means. I think it enriches our culture, and the section, so I go to others who know more about it than I do to teach me. My favorite was getting Bill Murray, who is a huge poetry fan, to tell us about five poems he loves—in person, at the Carlyle Hotel.

How many freelancers do you work with? Are there certain things you look for in a reviewer?

It’s just myself and an assistant on staff, so we do lean on freelancers. And while I have three or so regulars, I also like to have fun pairing a book with a reviewer. My favorite match-up was asking Mary Roach to review Ian McEwan’s novel in which the narrator was an unborn fetus. And I like to intermix big names with young new voices.

Is social media at all helpful to you in your role as a book editor?

I should use it more than I do in terms of promoting the Reading Room section, and I do try and follow what others are doing. Because Oprah.com is a separate entity, and O doesn’t have an online version, it’s hard to fully spread the word about how robust the section is.

What is the status of Oprah’s Book Club, and how does Oprah go about choosing which books to pick?

The book club is alive and well when we find the right book. The way it goes is that when I read for the section, I am always also thinking about what Oprah might like, either for the book club, or for some other purpose—film, movie, or just for pleasure. I send her books, and if something profoundly resonates, she will likely call me to tell me so. Then we talk about whether it could be a selection. We’d love for there to be picks on a more frequent basis, but that’s hard because the book has to be right and the timing for Oprah has to be right too. And of course, others are always sending books to Oprah—she’s not just hearing from me.

How have you seen the publishing world and the media landscape change over the past five years?

It seems indies and physical books are back. That’s cause for celebration. But print newspapers and magazines are, of course, facing challenging times, which means we have to keep innovating.

A frequent complaint in literary circles is that negative reviews take up space that could otherwise be used reviewing better books. Where do you stand on the value of publishing negative reviews?

I was told when I came to the magazine that we should pick books we think are worthy of coverage and share them with our readers. If we don’t like or love a book, we just won’t cover it. There are just too many good books to celebrate to devote space to the ones we don’t like.

Of those publications that still devote space to literary criticism, which are your favorites? Are there any book critics whose work you particularly enjoy?

I’m really going to miss Michiko Kakutani and Jennifer Senior. We also lost Bob Minzesheimer to brain cancer last year. And as everyone knows, the day of the standalone newspaper book review section, except for the New YorkTimes Book Review, is gone. But I’m looking forward to seeing what emerges, because I do think books are as important and as vital as ever, and there are lots of wonderful voices out there writing about them.

Name three books you’ve read in the past year that really knocked your socks off.

It still amazes me that the right book in the right moment can blow your mind. I just reread Night by Elie Wiesel, as there is a new edition with a foreword by President Obama. All I can say is that it’s as heartbreaking and beautiful now as it was when I first read it years ago. Future Home of the Living God, the latest from Louise Erdrich, absolutely floored me. It felt as urgent as a punch to the gut. The Hate U Give made me hopeful. Angie Thomas channeled her righteous anger into something incredibly brave and new, and she’s giving young people all over the country the sense that, yes, someone feels as I do.

Michael Taeckens has worked in the publishing business since 1995. He is a cofounder of Broadside: Expert Literary PR.

Reviewers & Critics: Kevin Nguyen of GQ

Kevin Nguyen is the digital deputy editor of GQ, where he writes about books, music, and popular media. He grew up outside of Boston in the 1990s and attended the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington. Since moving to New York City five years ago, he has run the Best Books of the Month feature at Amazon and was editorial director at Oyster, “the Netflix for books,” then Google Play Books after the tech giant acquired Oyster in 2015. He can be followed on Twitter, @knguyen.

At GQ you mostly work on reported features, but you also compile a Best Books of the Month feature. How many books do you receive each month, and of those how many are typically included in your roundups?

I went on vacation last week and returned to four mail crates of unopened galleys. So I’m getting something in the vicinity of fifty to seventy-five books a week. And honestly, I wish publishers wouldn’t send me things unsolicited. Most of those books are never going to be touched, and eventually they are shipped off to Housing Works for donation. In a given month I’ll try roughly twenty books. From those I’ll finish about half, maybe slightly more. And then I’ll pick about half of those—so it’s somewhere between four and six books each month. It really depends on how strong that month is.

In an ideal world, I would just request those books and not receive any mail. It feels like such a waste, but once you’re on those distribution lists, there’s no getting off them.

It’s funny. If I died today, the books would keep coming to the office, and I think about the poor person who would get stuck dealing with several thousand pounds of galleys each month. Which is why I plan to never die.

What sorts of things, if any, influence you when choosing which titles to include: blurbs, pre-pub reviews, large advances, social media buzz? What about your relationships with publicists and editors—do those ever hold any sway?

I keep a very long spreadsheet of books that are coming out, based on a combination of catalogs, publicist and editor pitches, Kirkus, previews from places like the Millions, and of course, word of mouth. Twitter can be a good signal, but its taste is fairly narrow.

I do read a lot of stuff blind, too. My equivalent of digging through the slush pile is browsing through everything available as a digital galley on Edelweiss.

Blurbs mean nothing. Same with big advances. Honestly, by the time the galley rolls around I’ve forgotten what I read about it in Publishers Lunch. I’ve been doing this for [checks watch], oh, Jesus, nearly seven years now. But I’ve got a system that works.

How conscientious are you about diversity—gender, race, sexual orientation, and so on—when choosing what to include? And do you try to pay attention to books published outside of the Big Five publishers?

Most people won’t cop to this, but I pay pretty close attention to making sure my list is inclusive. That spreadsheet I was talking about has a column that denotes if an author is a woman or a person of color, so I can make sure that there’s never a month when I am reading only white dudes. It feels weird—I am literally checking boxes—but it’s also a way to keep me honest.

On the upside, usually what I gravitate toward in terms of stories tends to be inherently diverse. You read enough and you see that a lot of books by white authors suffer from a kind of maddening sameness—thankfully you can identify this from the first fifty or so pages, if not sooner. Publishing has made slow strides forward in putting out books by people of color. Big lead titles are more diverse than ever.

And, of course, that spreadsheet also lists publishers. I make sure to read across the Big Five and indies each month. It’s probably the most useful column I have. Penguin Random House controls over 50 percent of trade publishing, and you could easily make the mistake of reviewing exclusively their books.

You’ve also edited some excellent literary features at GQ—Kima Jones’s interview with Colson Whitehead and Alex Shephard’s piece on Jonathan Safran Foer, to name just two examples. What goes into these features? Are you conceiving of them? Do you have much leeway when it comes to assigning literary coverage at GQ?

Both of those stories were my idea. Since we’re not a book-specific outfit, we have to find a story deeper than “this is a new book.” It has to speak to a broader audience, and that restraint had led to better pieces, in my opinion.

Kima and Alex did a great job with both, even though they were very different. Kima went deep with Colson Whitehead, and we were confident that the strength and reception of The Underground Railroad would justify going to such an intense place with the interview. For the Foer piece, it was a profile because we knew he was in an interesting inflection point in his career. Plus he surrendered some weird quotes about Natalie Portman. Love him or hate him, the guy is worth reading about.

You’ve written eloquently about the overwhelming whiteness in the U.S. literary culture and publishing industry. What critical steps do you think need to be made to diversify the literary ecosphere? In your recent Millions article you pointed out one bright spot of 2016: the momentous National Book Awards ceremony, so much of which was due to the National Book Foundation’s executive director, Lisa Lucas. Have you seen any other positive changes over the past couple of years?

As I mentioned earlier, publishing is a behemoth that is trudging along slowly in the direction of progress. But it still has a long way to go. Publishers used to excuse themselves by saying that the data showed books by people of color didn’t sell—a disingenuous claim. Well, in the past three years, we’ve seen some tremendously successful fiction by authors of color. So now editors and agents can’t say that anymore. Progress marches forward, and even the most reluctant figures have no choice but to be dragged along. I hope that in the next five or ten years, literary events will become spaces that are less oppressively white. I think we can get there.

You’ve had an interesting career path in the literary industry, with a notable stretch at the editorial side of Amazon, where you ran the Best Books of the Month feature. What was it like behind the scenes there? Did you and your team have full editorial control over which books you picked each month?

Amazon is bizarre, man! But the editorial team was—and still is—great. Real readers, with full editorial freedom. There was never any pressure to include or exclude anything, at least not in my time there. Remember that summer when Amazon was refusing to stock books from Hachette? It was one of the reasons I left the company. But one of the last Best of the Month lists I put together included Edan Lepucki’s California, a Hachette title we couldn’t even sell. Nobody at Amazon gave us a hard time about that, even when Stephen Colbert made that book a symbol against Amazon’s vicious business tactics. I don’t think Amazon is good for the world, but that editorial team is a bright spot in a bleak machine.

After Amazon you worked for two years at Oyster, an e-book streaming service billed as the “Netflix of books,” which was bought and later closed by Google Play. At Oyster you launched the Oyster Review, a remarkable online literary magazine that included reviews, interviews, essays, and book lists and featured an impressive roster of writers and critics. What went into creating and running that magazine?

A lot! Oh, man, but what a fun time. Basically, Oyster attempted to capture the indie bookstore feel and taste and personality in the digital space, as opposed to the big-box retail approach of Amazon. We hoped both could coexist, just like they do in brick-and-mortar.

The Oyster Review was the place where we’d establish our literary identity. Every great indie bookstore has one. And online, what you do instead of shelves and author events is publish reviews and essays and comics. I edited and art-directed the whole thing. And most people didn’t see this because it was in the Oyster app, but there was a whole mobile experience that had to be designed for too. So from conception to construction to day-to-day editing and production, I had a hand in all of it. And I loved doing it.

Obviously, it didn’t totally work out. But Google acquired the company, and one of the big selling points to them outside the engineering was the Oyster Review and all the fine editorial work we’d done. I’m very proud of that. I mean, has a tech company ever acquired a literary magazine before? It might be the first and last time that ever happens.

In addition to reviewing books and writing about literary culture, you’ve written widely about TV, movies, and gaming. Have your interests in fields outside of literature influenced and informed your literary criticism and vice versa?

Oh, definitely. You can tell the reviewers who do only books. There’s a strange stilted myopia there. I think the best writers have broader interests and can talk intelligently about other mediums.

Of those publications that still devote space to literary criticism, which are your favorites? Are there any book critics whose work you particularly enjoy?

Bookforum is probably the most complete publication out there. It has a strong perspective and tone and taste. Plus, the reviews are damn good. I wish they’d do a little more online so more people could see it.

I keep waiting for someone to start the Pitchfork of books, but every new book-related site that launches ends up feeling so flat and overly positive. Oh, and too damn white.

Name three books you’ve read in the past year that really knocked your socks off.

White Tears by Hari Kunzru by a mile. What a tremendous, smart, weird book. I tore through The Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann in a couple of days. And Ottessa Moshfegh’s short stories in Homesick for Another World have stayed with me in strange and surprising ways.

Michael Taeckens has worked in publishing since 1995. He is a literary publicist and cofounder of Broadside PR.

Reviewers & Critics: Dwight Garner of the New York Times

Dwight Garner is one of the most beloved book critics writing today. His New York Times reviews, whether positive, negative, or mixed, are always entertaining—not an adjective most would use to describe book criticism. Language comes alive in his reviews; one gets the sense that he’s playing with words and having fun along the way.

Raised in West Virginia and Naples, Florida, Garner started writing for alternative weeklies such as the Village Voice and the Boston Phoenix after graduating from Middlebury College. In 1995 he became the founding books editor of Salon, where he worked for three years, followed by a decade as senior editor at the New York Times Book Review. He has been a daily book critic for the New York Times since 2008. The author of an art book, Read Me: A Century of Classic American Book Advertisements (Ecco, 2009), he is currently working on a biography of James Agee. You can follow him on Twitter, @DwightGarner.

Raised in West Virginia and Naples, Florida, Garner started writing for alternative weeklies such as the Village Voice and the Boston Phoenix after graduating from Middlebury College. In 1995 he became the founding books editor of Salon, where he worked for three years, followed by a decade as senior editor at the New York Times Book Review. He has been a daily book critic for the New York Times since 2008. The author of an art book, Read Me: A Century of Classic American Book Advertisements (Ecco, 2009), he is currently working on a biography of James Agee. You can follow him on Twitter, @DwightGarner.

With Goodreads, Amazon, and countless blogs, it seems like everyone’s a book critic these days. What credentials do critics have that make them critics? And what was your own path to becoming a professional book critic?

No credentials are required to write criticism: Either your voice has authority or it doesn’t. Either it has style and wit or it doesn’t. Thank God there’s no grad program, no Columbia School of Criticism. Nearly all the best critics are to some degree autodidacts. Their universities are coffee shops and tables covered with books.

I grew up in a house that didn’t have many books in it, beyond the Bible and Reader’s Digest Condensed Books, at any rate, and where culture wasn’t particularly valued. I loved reading critics—book critics, movie critics, rock critics—from the time I was young. They gave me someone to talk to, in my mind, about the things I cared about. I’m the kind of reader who’s always flipped first to the “back of the book” of magazines, or to the arts pages of any newspaper. I worked in a record store during high school and wrote rock reviews for the school newspaper. This makes me sound almost cool; I was not almost cool. I was also the editor of my college paper. But I prefered writing book reviews, which I also did. Writing book criticism seemed to me then, and seems to me now, a chance to talk about everything that matters—the whole world, really.

You can’t trust Amazon reviews; I’m less certain about Goodreads, which I don’t know enough about. I’ve found it to be a terrific resource for certain kinds of information. Good writing is good writing wherever it appears, definitely including blogs. The more voices the merrier.

Facebook and Twitter have been a terrific boost to authors and publishers. Has social media aided your role as a critic?

I forget who it was who said that Facebook is a smart service for simple people while Twitter is a simple service for smart people. Ouch, right? But true enough. Twitter is companionable if you follow the right people, and you can dip into real-time conversations about books. You can see what people are saying; you can glean links to reviews. If people I respect are talking about a book, and it’s not on my radar, I’ll put it on my radar. I’ve reviewed books because I’ve seen interesting people talking about them.

Does buzz—a big advance or an author’s name—influence you?

Buzz matters and it doesn’t matter. Occasionally you might weigh in on a book because you have something to add about something everyone is talking about, perhaps to deflate the hype. Book critics envy movie critics only in that movie critics write weekly about things people are talking about and are likely to see.

Are you able to select which books you review or are they assigned to you? If you have a relationship with a publicist or editor, does it tip the balance?

At the Times we pick our own books. The daily books editor, Rachel Saltz, is a mensch, though, and is great at suggesting things. I review six or seven books a month; my schedule is two reviews one week, one the next. It’s about [equivalent to] the schedule of a major-league pitcher. Two or three of those books I know almost on contact that I want to review, because I’m interested in the author or I’m interested in the topic. After that, it gets headache-making. I sit down once a week or so with a big pile of galleys and poke around in them, looking for signs of life.

Relationships with publicists and editors (I don’t have many of those) don’t matter, either—a book is worthwhile or it isn’t, and the good ones know that. Having said that, a really good editor or publicist will know that very rare occasion to send up the bat signal, to indicate that a genuinely extraordinary book is on the horizon. Alas, even the bat signal, three times out of five, turns out to be hype.

Given the inordinate amount of review copies you must receive daily—just how many do you receive on an average day?—it seems like an e-reader would possibly help lighten the load. But the allure of physical books—even with galleys—is so hard to resist, isn’t it?

I get twenty-five to thirty books a day, and they really pile up on the porch. Last summer an elderly woman heard our three dogs barking—the windows were open, and we were out—and she saw the huge, sloppy pile of mail out front. She knocked on our neighbor’s door and asked, “Do you think the person who lives there is dead?”

I read e-books sometimes, mostly on my phone, but I don’t like to review from them. I write all over my books, I really mark the shit out of them, and I’m not confident that the notes I take on, say, a Kindle, will be recoverable in ten years. They’ll vanish, like the e-mail messages or the photos you meant to save from the laptop you owned three laptops back. So give me the dead-tree edition. I suspect I’ll always feel this way. Oddly, I do prefer to read magazines now on my phone or laptop. I find it easier on the eyes.

Have you ever changed your mind about a book that you praised or panned years earlier?

I deeply regret one or two reviews I’ve written. I was too hard, once, on a writer with a first book out; I still mope about my arrogance. These are the kind of reviews I’ve heard described as, “You know that thing you’ve never heard of? It sucks.” I regret a few raves, too—times when I’ve gotten carried away. I want readers to trust what I have to say on an intergalactic level but also on a bank-card level. Books aren’t cheap. I don’t want thousands of people walking around thinking they’d like to dun me for $26.95.

When you’re reviewing a new book from an author with previous books to his or her name, do you read the author’s backlist as well?

Very nearly always. It matters especially with fiction. I recently read the first three volumes of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle in just a few days. Each is five hundred pages or so. It felt like I was back in college, cramming for an exam. But those are beautiful books, and I feel lucky to have been able to submerge myself in them. It was like having a lovely fever.