“There are certain writers whose prose is so deft and beautiful that reading them can inspire whatever I happen to be working on, even if the style, setting, or genre are completely different. One is Thomas Pynchon, whose prose I’ve been obsessed with ever since I discovered his 1966 novel TheCrying of Lot 49. I’ll often go back to the first paragraph of that book to remind myself that it’s possible to write something complex, lyrical, and full of specific detail, but also something that’s funny and that really moves. Hilary Mantel is another such writer. Her Man Booker Prize–winning novel Wolf Hall has a remarkable way of fusing sensory detail with Thomas Cromwell’s perspective, as well as shifting from free indirect discourse to authorial commentary. Ultimately, I think it comes down to rereading the classics (or whatever you consider to be a ‘classic’). With contemporary literature, you can get caught up in debates over the style that’s in vogue at the moment, ‘spare prose’ or ‘hysterical realism’ or whatever. I go back to the prose that I know will always bring me what I need to keep writing, no matter what era we’re living in.”

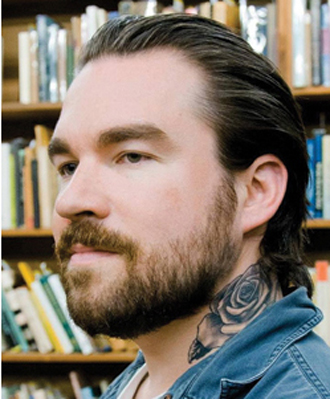

—Aatif Rashid, author of Portrait of Sebastian Khan (7.13 Books, 2019)

Aatif Rashid

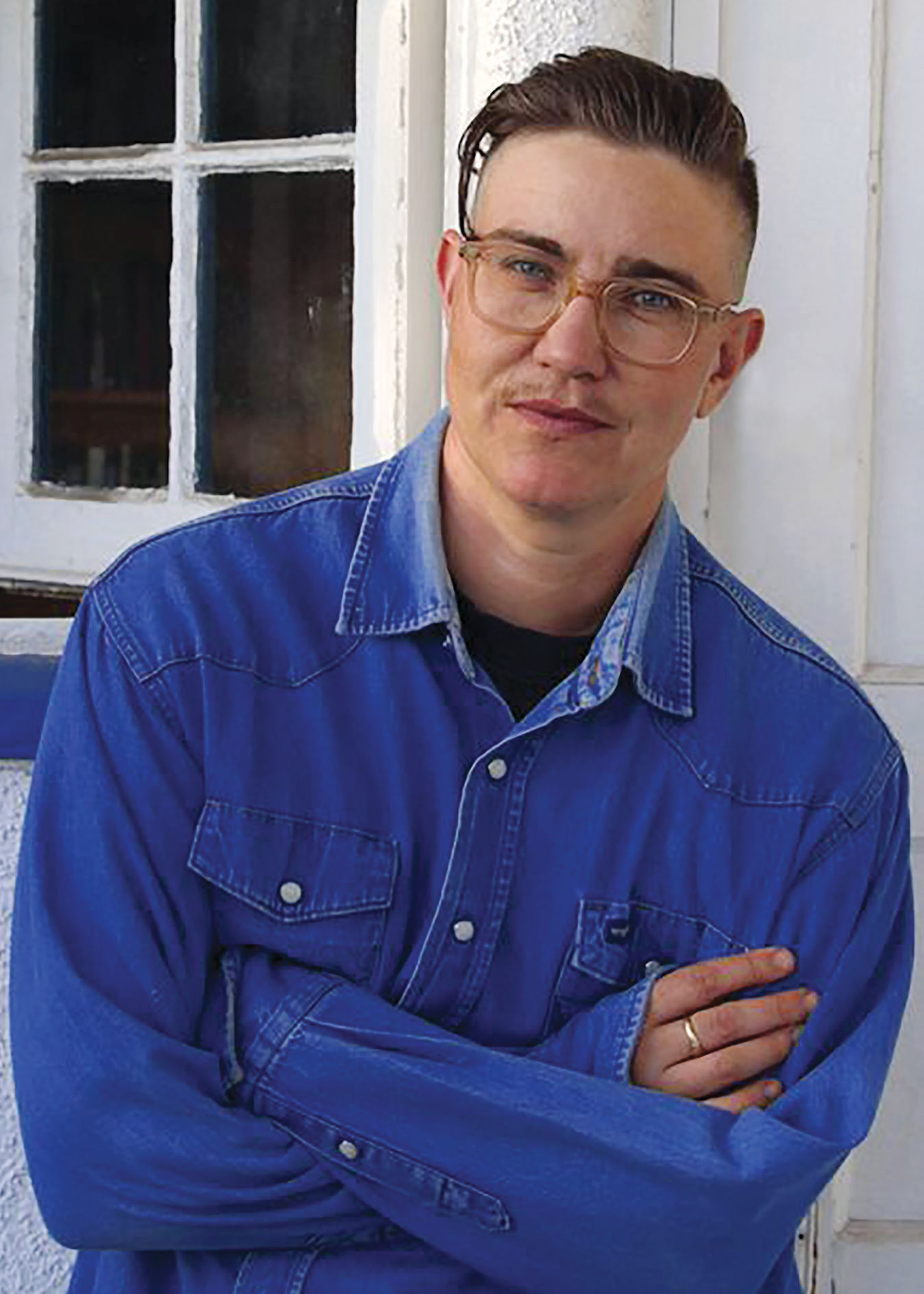

Jillian Weise

Jillian Weise reads her poems “Semi Semi Dash,” “Café Loop,” and “Poem for His Girl,” from her second collection, The Book of Goodbyes (BOA Editions, 2013), at the Academy of American Poets’ 2013 Poets Forum Awards Ceremony. Weise’s third collection, Cyborg Detective (BOA Editions, 2019), is featured in Page One in the September/October issue of Poets & Writers Magazine.

Reviewers & Critics: Daniel Mendelsohn of the New York Review of Books

One of the most prominent and liveliest contemporary critics in the United States, Daniel Mendelsohn began contributing reviews, op-eds, and essays to a variety of publications, including Out, the New York Times, the Nation, and the Village Voice, while still a graduate student at Princeton University, where he received his doctorate in classics in 1994. Over the years he has written for an array of publications, including the New Yorker; the New York Times Book Review and Harper’s, in both of which he had regular columns; and New York magazine, where he was the weekly book critic. In February Mendelsohn was named editor-at-large of the New York Review of Books (NYRB) and director of the Robert B. Silvers Foundation. Among his many awards is the Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing from the National Book Critics Circle.

Mendelsohn’s books include the memoir An Odyssey: A Father, a Son, and an Epic (Knopf, 2017), an NPR Best Book of the Year; the internationally best-selling Holocaust family saga The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million (Harper, 2006), winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award and the National Jewish Book Award; and The Elusive Embrace: Desire and the Riddle of Identity (Knopf, 1999), a Los Angeles Times Best Book of the Year. He is also the author of three collections of essays—Ecstasy and Terror: From the Greeks to Game of Thrones, forthcoming in October from New York Review Books; Waiting for the Barbarians: Essays From the Classics to Pop Culture (New York Review Books, 2012); and How Beautiful It Is and How Easily It Can Be Broken (Harper, 2008)—and his translation, with commentary, of the complete poems of Constantine Cavafy, published by Knopf in 2009, was a Publishers Weekly Best Book of the Year. He is currently at work on a new translation of the Odyssey for the University of Chicago Press and teaches literature at Bard College.

What was your path to becoming a literary critic?

I’d always dreamed of being a critic—at least since the 1970s when I was a teenager and first started reading the New Yorker seriously. I was enthralled by the critics in that magazine during that era—enthralled by the idea that everything was potentially the object of critical exegesis, from the poems of James Merrill, as reviewed by Helen Vendler, to cabaret performances by Julie Wilson, reviewed by Whitney Balliett. In graduate school, while I was toiling away at my dissertation, I’d relax by writing reviews of books for the weekly literary paper there; when I finished my degree I abandoned the academic track and moved to the city and started writing and reviewing full time for pretty much anyone who would take my pieces—at that time, in the early to mid 1990s, lots of gay magazines that would fold just before they paid you. Within a year or so I had pieces in the Nation and Village Voice, and from there I moved to the New York Times Book Review, then under the sterling leadership of Chip McGrath, which was my first regular platform, and for which I wrote many pieces between 1996 and around 2006. That was what really launched me. In 2000 Bob Silvers asked me to do a piece, and that was the beginning of my close relationship with the New York Review of Books.

Do you think literary criticism can be taught, and do you think it should be taught in MFA programs?

I don’t think any kind of writing can be “taught.” Either you’re a writer or you’re not, and it doesn’t matter what kind of writing we’re talking about—fiction, criticism, whatever. I do think that people who are gifted can be helped along, their craft refined and improved, by good teachers; so in that sense, sure, let criticism be taught in MFA programs. I myself never studied writing; I just read a lot. You start by imitating the people you like, and soon you develop your own voice.

What advice do you give to young students who want to become professional critics?

Do your homework. You can’t sit down to review something unless you’ve really immersed yourself in every available resource: You have to read—or watch, or whatever—everything the author or creator has done, you have to do research, you have to have a solid background before you even dream of approaching the work you’re supposed to be reviewing. This is time-consuming, obviously, but it’s the only way to get good results. I suppose I get this from my training as a scholar: I still vividly remember a professor of mine at UVA saying—apropos of a paper I was about to write about the Odyssey, as it happens—“Well, you can’t write anything until you’ve read everything.” That’s my advice. Criticism is serious business, and if you take it seriously, editors will respond.

Is there ever anything from the publishing side that raises your interest in a book or author—a sizeable advance, notable blurbs, your relationship with an editor or publicist?

No. I’d be very suspicious of a critic who had “relationships” with editors or, God forbid, publicists. What has that got to do with the activity of criticism? The buzz, the hype, the cloud of excitement that eager editors and publicists want to create around a book or play or movie are precisely what the critic should be seeing through, should be resisting. So why would a responsible critic be in bed with those people?

Ugh. That said, it often happens—certainly it does with some of my pieces—that you’re looking at a new book or movie or whatever as a sign of some kind of larger cultural phenomenon, and in that case it’s legitimate to cite some of the “surround”—the sales, the public reaction, and so forth. I wrote an analysis years ago of Alice Sebold’s novel The Lovely Bones, which was such a phenomenon—they couldn’t print the books fast enough—that it seemed important to mention the sales, the overwhelming public appetite for the story that she was telling. But that’s the only time, I think, that a critic should pay attention to that stuff.

How conscientious are you about diversity—gender, race, sexual orientation, etc.— when choosing which books to review?

I don’t think critics can or should be ruled by those concerns. You can only write well about what interests you, what resonates for you intellectually and aesthetically, and you should only please yourself. That said, I think publications should be sensitive to issues of diversity and balance—of writers, of subjects. That’s appropriate. But critics have to be free to write about the subjects that really animate them.

Tell us a little bit about your editor-at-large role at the New York Review of Books. Do you choose what to write about?

My new role at the NYRB doesn’t impinge on my editorial relationship with the magazine at all. Since I started writing for Bob Silvers in 2000, it’s been give-and-take: They’ll think of something that might be right for me, or I’ll have an idea about something that I’d like to do. And that’s how it has worked with the other publications I’ve written for over the years: the New Yorker, the New York Times Books Review, a few others. I very much enjoy when editors suggest things that would never have occurred to me as good subjects—it takes you out of yourself and makes you stretch, which is healthy, whether it’s Bob Silvers insisting that Mel Brooks was a good subject to my editor at Town and Country asking me for a piece about adultery and the novel. Fun!

My role at the Review as editor-at-large has to do with what you might call “outreach.” We have the greatest pool of intellectual, journalistic, and critical talent in the world, and until now that talent has basically had only one outlet: the magazine and website. Given my long relationship with the magazine, and the fact that I’m out in the world quite a lot as an author and lecturer and have a pretty good sense of how these things work, Rea and Patrick Hederman thought that I’d be useful in helping to create new ways of bringing the Review and my fellow contributors to a larger public. So I’m working on creating a few series of public discussions, to start this fall, that will bring our contributors on stage for conversations with people in various fields. One series, in partnership with the David Zwirner Gallery, will be about contemporary art, literature, and how they intersect with issues of power—critics, audiences, collectors, governments. Another, in partnership with NYU, will focus on the idea of what “classics” in literature are: how they get canonized—and uncanonized—how authors and works go in and out of fashion. We’re also talking to Monticello and the Frick about collaborations, and we’re dreaming up new ways to reach out to colleges, community colleges, and universities. And we’re starting a podcast! So it’s a busy and exciting time in which we’ll build on the Review’s strengths to get out into the world more in a very strong way.

In your forthcoming book, Ecstasy and Terror: From the Greeks to Game of Thrones, you state that “any call to eliminate negative reviewing is to infringe catastrophically on the larger project of criticism.” How do you think negative reviews contribute overall to the cultural dialogue?

A culture that only cheerleads and celebrates is a vapid culture—a culture of marketing, not thinking. With respect to literature, such marketing is, as I mentioned earlier, properly the province of publishers and publicists—and that’s fine. All writers benefit from publishers’ marketing and advertising: I have myself. No shame in that. But precisely because the culture as a whole is so overwhelmingly commercial, it’s vital that professional, public, literary, and cultural criticism remain independent. Negative criticism is, in part, what fights against the commercial, or the merely stupid, or vulgar; it is a form of resistance, a reminder that we must think for ourselves and not have our judgments coopted by advertising and the ephemeral.

Having said that, I would stress urgently that there is a right way to do negative criticism: It has to be reasoned, it cannot be ad hominem, and so forth. Indeed, I’d say that now, with the explosion of vituperative discourse that is the hallmark of much Internet culture, doing proper, measured negative criticism importantly models how not to like something. In an era in which so many exchanges—literary ones, too—devolve into snark and name-calling, we need good negative criticism perhaps more than ever.

In an interview with Laura Miller you stated, “I would say you get more out of reading reviews you disagree with because it forces you to sharpen your own thoughts.” Can you expound upon this?

This is precisely what I mean by the importance of negative criticism—not just negative in the sense of “disapproving,” but negative in the sense of “opposite,” “resistant to what most people think.” I think when I was talking to Laura we were speaking of reviews of one’s own books, and I certainly continue to think that reading a review that is original, that resists the common take, can provoke an author to real insight into his or her own book. When you write, you’re in your own head: It’s all you. I can’t imagine any serious writers really think about pleasing their readers: You write to please yourself, to scratch an itch, to answer a question that burns for you. So a negative or resistant review acts in much the way that a good editor will act: It forces you to see another way of looking at your material, and that’s very salutary, I think.

Have you ever changed your mind about a book that you praised or panned years earlier? Has a work of criticism ever changed your opinion of a writer’s work?

I don’t think I’ve changed my mind in the sense of “Gosh, I was totally wrong about that.” But I’ve been writing as a critic for thirty years now, and as you get older your general aesthetic can shift; things you used to love don’t excite you anymore, or things that once left you cold start to make sense to you. I once wrote a Bookends column about this for Pamela Paul at the New York Times: I used the example of Catcher in the Rye, which when I reread it for the first time since I was a teenager I found totally unbearable.

As for a review that changed my mind: Not really. But shrewd reviews can make you consider things differently. As many people know, I had very strong objections to Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, but when I read an interesting piece in the New Yorker by Elif Batuman about how the novel had captivated her, I could suddenly see how an intelligent person might get caught up in the book. I still loathe the novel, but because of Elif’s essay I suppose I’m much more tolerant now of people who liked it than I was two years ago.

You’ve published multiple books of your own. How did it feel to be operating from the other side, having your own literary work assessed by fellow critics? Has that experience instilled any sense of empathy with authors whose works you choose to review—or does identifying with the subjects of your critical work lead to a slippery slope?

I like to joke that my training as a classics scholar did me a great service, since I always write about works as if their authors have been dead for two thousand years—their feelings, their hopes and dreams, their biographies and secrets, simply aren’t an issue. All kidding aside, I don’t really think about authors and their feelings when I write reviews, and I’d hope that people reviewing my books aren’t worried about my feelings in evaluating my work. Indeed, I must say the question of empathy seems to me to be grossly misplaced. Obviously, one would never want to write—or be the recipient of—anything that was cruelly personal, and even the harshest criticism of a work should be grounded in the text, demonstrable, and measured—the criticism should serve the argument. The author of the work under review should, therefore, never feel that it’s personal, even if it’s very hard. What I do feel for is literature—or film, or theater, or dance, or art. That’s what I’m passionate about, and my passion for a genre is what guides my evaluation of people’s works in that genre. I feel protective of writing, not writers.

For that reason, I always feel that even if a review of a book of mine is harsh, if it’s motivated by a genuine critical impulse, it is legitimate and has to be accepted. Nobody likes getting bad reviews, but it’s part of life as a creative person: Not everyone is going to like your stuff. And since you can always tell when a review is personal, those are pretty easy to discount. The only thing a writer wants is an intelligent review, not a “good” review.

Has social media been helpful at all in your role as a critic?

No. I’ve certainly had interesting and sometimes feisty conversations with people on social media and have even befriended a number of people there; and it’s often fascinating to see how “ordinary,” in the technical sense, readers and audiences are reacting to something in the culture. But the fact is that, in the end, you can only listen to yourself. Social media for me is an often fun distraction from real work, and that’s pretty much it.

Who do you think are some of our finest literary critics working today?

Critics, not just literary, whom I trust these days include Madeleine Schwartz, Christian Lorentzen, and Vinson Cunningham.

What books that you aren’t reviewing are you most looking forward to reading in the near future?

What with everything else I have going on—my own writing, the NYRB, the Robert Silvers Foundation, and Bard—I have relatively little time for “pleasure” reading: The summer is when I try to catch up. Right now I’m dying to get to Brenda Wineapple’s book about Andrew Johnson’s impeachment, Andrew Sean Greer’s Less, The Overstory by Richard Powers, and Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls—although I do wish her editor had forced her to think of a title a bit less Hannibal Lector-ish. I think her Regeneration Trilogy is one of the great works of the twentieth century; how could I not want to read her take on the Iliad?

Michael Taeckens has worked in the publishing business since 1995. He is a cofounder of Broadside: Expert Literary PR (broadsidepr.com).

Reviewers & Critics: The Complete Series

Launched in late 2014, Reviewers & Critics is a regular series of interviews with the professional writers, readers, and thinkers whose job is to start conversations about contemporary literature. Whether they do this work in newspapers or magazines, on blogs or Twitter—and whether you agree with their opinions or not—good book reviewers and critics provide a cultural service that is arguably more important than ever. As more brick-and-mortar bookstores close and the landscape of book publishing shifts and adjusts—to say nothing of the shrinking real estate for traditional reviews—reviewers and critics continue to write and talk about books using whatever medium is available. This series is an attempt to see more clearly the people behind the bylines and Twitter handles and to better understand the role they play in literary culture.

Daniel Mendelsohn of the New York Review of Books

8.14.19

One of the most prominent and liveliest critics in the United States discusses whether or not literary criticism can be taught, the value of negative criticism, and more.

Maureen Corrigan of NPR’s Fresh Air

2.13.19

In this continuing series, a book critic discusses the unique challenges of reviewing for radio and how she picks the books that make it on the air.

Laurie Hertzel of the Star Tribune

10.10.18

In this continuing series, a book critic discusses Minnesota’s thriving literary community and the importance of reviewing small-press titles.

Sam Sacks of the Wall Street Journal

8.15.18

In this continuing series, a book reviewer discusses the art of literary criticism—from the value of negative reviews to critics he admires.

Laila Lalami of the Nation

4.11.18

An author and book reviewer discusses both sides of the writer-critic divide.

Leigh Haber of O, the Oprah Magazine

12.13.17

The books editor at O, the Oprah Magazine discusses how she got her start in the literary world, the selection criteria behind Oprah’s Book Club picks, and her favorite books of the year.

Kevin Nguyen of GQ

8.16.17

The digital deputy editor of GQ discusses his Best Books of the Month feature and the state of diversity in publishing.

Parul Sehgal of the New York Times Book Review

4.12.17

Parul Sehgal discusses her path to literary criticism, her passion for international literature, and today’s finest reviewers.

Laura Miller of Slate

2.15.17

Laura Miller discusses how she chooses books, the effect of the Internet on literary criticism, and her belief that reading is as profoundly creative as writing.

Steph Burt

8.17.16

Steph Burt, acclaimed critic, poet, and Harvard professor, talks about their path to becoming a poetry critic, working as both a poet and a critic, and how the internet has greatly expanded the conversations surrounding poetry and poetics.

Carolyn Kellogg of the Los Angeles Times

6.14.16

Los Angeles Times book editor Carolyn Kellogg talks MFAs, publishing optimism, and how she’s revolutionizing her new position in the shifting landscape of book reviews.

Pamela Paul of the New York Times Book Review

4.13.16

New York Times Book Review editor Pamela Paul shares her insights on the ethical and practical challenges of being the head of the last of the stand-alone newspaper book review sections.

Michael Schaub

12.15.15

The latest installment of Reviewers & Critics features Michael Schaub, an incisive—and hilarious—literary critic and former Bookslut contributor.

Isaac Fitzgerald of BuzzFeed Books

by Michael Taeckens

8.19.15

Isaac Fitzgerald, editor of BuzzFeed Books, talks about the growth of the site’s book review section, what a typical day in the BuzzFeed office looks like, and how the Internet has changed the discourse around books.

Jennifer Day of the Chicago Tribune

6.17.15

Jennifer Day, the editor of the ChicagoTribune’s Sunday books section, Printer’s Row Journal, discusses her commitment to assembling the best literary criticism on both the local and national level.

Ron Charles of the Washington Post

4.15.15

Ron Charles of the Washington Post and the Totally Hip Video Book Review series gives his insights on the ethical and practical challenges of being a book critic for a major newspaper.

Roxane Gay

2.10.15

The second installment of Reviewers & Critics features longtime book critic and culture essayist Roxane Gay, a true powerhouse in literary circles.

Dwight Garner of the New York Times

12.15.14

In the inaugural installment of our new feature, Reviewers & Critics, New York Times book reviewer Dwight Garner talks about his experience as a critic—the required credentials (or lack thereof), how to cut through the hype, the role of negative reviews, and more.

Reviewers & Critics: Sam Sacks of the Wall Street Journal

Sam Sacks grew up in Silver Spring, Maryland, studied literature at Tufts University, and received his MFA in creative writing at the University of Arizona in Tucson. In 2005 he moved to New York City and worked for years at various bookstores, including the Strand and Housing Works Bookstore, where he still can be found every Saturday volunteering. In 2007 he cofounded the online literary journal Open Letters Monthly, which he edited for ten years, and today he is an editor at its sister site, Open Letters Review. He started writing the Fiction Chronicle column for the Wall Street Journal when the paper inaugurated the weekend Books section in September 2010. His criticism has appeared in Harper’s, the London Review of Books, the New Republic, Commentary, the Weekly Standard, Prospect, Music and Literature, and the New Yorker’s Page-Turner.

What path led to you becoming a literary critic?

I’m the product of the vanishing, much-lamented free city weekly. After college, on the encouragement of a friend, I wrote a book review that was published in Pittsburgh’s secondary alternative newspaper Pittsburgh Pulp. As I moved around in the years that followed, I kept writing reviews for beer money at places like Flagpole magazine in Athens, Georgia, the Tucson Weekly, the Las Vegas Weekly, and the New York Press. Around the time that this kind of outlet started drying up for me I cofounded, with Steve Donoghue and John Cotter, an online literary journal, Open Letters Monthly. This wasn’t quite the earliest Wild West days of online book blogging and reviewing, but it was early enough that it was still possible to throw together a site without any money and get it taken seriously on the strength of the writing alone. It’s here that I started writing much longer criticism, with the added motivation of wanting to make the site a success. After a few years I had built up a pretty extensive body of work and started to get paying gigs, and through some ridiculous good fortune, the gigs turned into viable full-time employment.

You review fiction exclusively. Is this by choice?

Fiction is what I love most and understand best, but the exclusivity is more a reflection of my role at the Wall Street Journal, which is to write a column reviewing the week’s new and noteworthy literary fiction. If I had unlimited time—and some allowance to learn on the job—I would happily review criticism, literary biography, travel writing, nature writing, essays, poetry, and who knows what else.

You’ve reviewed quite a lot of fiction in translation and novels and short stories published by small presses. Is this the kind of work you personally prefer?

I sometimes wish I could wave a magic wand and erase these kinds of distinctions from readers’ minds, my own included. I know that categories are necessary for marketing purposes and that readers can find them useful, but it dismays me that translated and small-press fiction gets balkanized into highbrow genres aimed at narrowly selected audiences. If I review more of these books than some critics, it’s only because I do my best to treat them as though they’re no different from more mainstream books. Which they’re not, in the important ways. Good books are good books and are for everyone.

How many review copies do you receive per week, and of those how many are you able to review?

I’m not quite sure because they’re all sent to the Wall Street Journal. There the editors set apart the fiction for me, and I go in once a week to sort through the new arrivals and organize them by month of publication. The publication calendar I made for July, which is a somewhat light month, had fifty-three titles. Then I fill a tote bag with books I’ll want to read or read into—I generally bring home ten to fifteen books every week. On average I’ll end up reviewing three of them.

How many books do you read each week for work?

Same amount—usually three books a week.

Is there anything from the publishing side that raises your interest in a particular book or author—the size of the advance, notable blurbs, your relationship with an editor or publicist?

I do my best not to think about extra-literary things like that because they tend to make me irritable, which is not a good frame of mind to have going into a book. Blurbs particularly annoy me because of the way they parody actual reviews, though I realize I should lighten up. Naturally I pay attention when publishers really get behind a book. But personal recommendations are the most helpful. Publicists and editors are first and foremost book lovers, and it’s hard not to want to share in their excitement when they get genuinely enthused about something they’re bringing out. This also makes the din of prepublication acclaim more manageable, because an honest publicist can play the “genuinely enthused” card only so many times.

Have you ever changed your mind about a book that you praised or panned years earlier?

Not that I can think of. But this is really just because I rarely have time to reread contemporary novels I’ve already reviewed.

Has a work of criticism ever changed your opinion of a writer’s work?

Yes and no. Nothing can take the place of a direct encounter with a book. But if criticism doesn’t lead me to change my own judgment, it wonderfully broadens my understanding and appreciation of what a writer is doing. Take Philip Roth, a writer about whom everyone has an opinion. I have never enjoyed his books, and when I read them I have great difficulty seeing past what I think are massive limitations: the self-pity, the blaming, the absence of doubt or introspection. But because of the wonderful criticism I have read of him—by Wyatt Mason, D. G. Myers, Claire Messud, Laura Tanenbaum, and countless others who aren’t immediately coming to mind—I have a deepened respect for his importance to the canon: for the liberating power of his anger, for his willingness to change his style, for the uncompromising nature of his view of life, and so on. This is, incidentally, why literature is so enriching—we experience it subjectively and objectively all at once. Every book is both personal and communal, so the possibilities of interpretation are endless.

What is your opinion about the value of negative reviews?

Negative reviews are healthy, stimulating, completely necessary. In my view there are fairly stringent moral prohibitions against judging people in life, but art is where one can love and hate at passionate extremes. When I have regrets about my own reviewing, it’s usually when I’ve shied away from negativity into some featureless middle ground. I should say that the best negative reviews are not simply hatchet jobs but pieces that use a book’s weaknesses or transgressions to illustrate a larger idea.

If you could change one thing about the book-reviewing process or the world of literary criticism, what would it be?

I wish reviewing paid more. This isn’t a passive-aggressive complaint about my own lot, by the way. As mentioned I’m exceptionally fortunate to make a living as a critic. Most people can’t. God bless the exceptions, but most outlets don’t pay enough to justify the work and time that goes into a long, involved work of criticism, meaning that countless important pieces have gone unwritten for lack of fitting compensation.

Social media—is it helpful or a hindrance?

I’m only on Twitter, and I use it only to procrastinate, unfortunately. I admire people who make it work for them.

Which book critics, past or present, do you particularly admire?

It’s more fun to stick to the present. The most important thing for a critic is to have a regular berth somewhere, and, notwithstanding my earlier lament about money, there are more really good placements than is widely recognized. I make a point to read everything by Lidija Haas at Harper’s, Christian Lorentzen at New York, Andrew Ferguson at the Weekly Standard, Sarah Nicole Prickett at Bookforum, Barton Swaim on political books for the Wall Street Journal, the two recent hires, Parul Sehgal and Jennifer Szalai, at the New York Times, Katherine A. Powers at the Barnes and Noble Review, and, maybe my favorite, Colm Tóibín at the London Review of Books.

What books that you aren’t reviewing are you most looking forward to reading in the near future?

I let the serendipity of used bookstore browsing decide most of my non-work reading, so I’m not sure. But I do have two books on my phone that I’m slowly reading during the interstices of the day: The Mixer by Michael Cox, a history of soccer tactics in the English Premier League, and The Novel: A Biography by Michael Schmidt. I’m up to the chapter on Fanny Burney. It’s delightful.

Michael Taeckens has worked in the publishing business since 1995. He is a cofounder of Broadside: Expert Literary PR (broadsidepr.com).

Sam Sacks

Reviewers & Critics: Laila Lalami of the Nation

Laila Lalami is well known for her extraordinary fiction; she is the author of the novels Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits (Algonquin Books, 2005), Secret Son (Algonquin Books, 2009), and The Moor’s Account (Pantheon, 2014), the most recent of which appeared on the longlist for the 2015 Man Booker Prize and was named a finalist for that year’s Pulitzer Prize. But she is equally well known for her sagacious literary criticism and writings on politics and culture. Over the past thirteen years she has written book reviews for a wide array of outlets, including the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, and the Boston Globe. Lalami reviewed fiction and nonfiction for the Nation from 2005 to 2016, at which point she started writing the Between the Lines column for the magazine. Since 2016 she’s also been a critic-at-large—along with nine other writers, including Alexander Chee, Marlon James, and Viet Thanh Nguyen—for the Los Angeles Times, where she writes mostly about the literary life. Lalami, who was born in Rabat, Morocco, and educated there as well as in Great Britain and the United States, is likewise highly regarded because of her popular literary blog, Moorish Girl, which she launched in 2001 and, after the publication of Secret Son, folded into her website, lailalalami.com. She currently teaches creative writing at the University of California in Riverside. You can follow her on Twitter, @LailaLalami.

You got your start writing for the Oregonian in 2005, reviewing books by Reza Aslan, Luis Alberto Urrea, Salman Rushdie, and Zadie Smith. What path led you to literary criticism, and how did that relationship with the Oregonian begin?

At the time I had just moved to Portland from Los Angeles and was working on my first collection of short stories. It was a lonely time in my life—I knew perhaps two or three people in the entire city—so the book section of the Oregonian became a kind of conversation I missed having about books. I also had a literary blog where I wrote about stories or novels I was reading, and that helped me broaden my reading interests. I think I was drawn to criticism because it gave me an opportunity to articulate what I thought about a piece of writing—what it tried to do, whether it succeeded, and, if so, how it succeeded. But the only way to find out if I could do it was to give it a try. So I wrote to Jeff Baker, who was the book review editor for the Oregonian, and asked if he might be interested in having me write about a book I’d just finished. It was slated to be published the following month, so it was already assigned, but he looked up some of my writing on the blog and asked me if I was interested in Luis Alberto Urrea’s The Hummingbird’s Daughter. Before that review came out we were already talking about doing a piece on Reza Aslan’s No god but God. Some weeks later Adam Shatz, who at that time was the literary editor of the Nation, asked me if I would be interested in reviewing for the magazine. This gave me the opportunity to write longer pieces on the work of Tahar Ben Jelloun, J. M. Coetzee, Joan Scott, and Percival Everett, among many others.

You’ve also published many essays and opinion pieces over the years—including multiple pieces for the New York Times Magazine, the Nation, and the Los Angeles Times. How does your literary criticism inform your political and cultural analysis, and vice versa?

When I write literary criticism, I try to be open to the premise of the work, to discover what the intention was, and whether that intention was fulfilled in the text. I examine the choices that have been made, in terms of characterization or point of view or tone, and whether these choices were effective. I think of it as a journey of exploration into another writer’s mind. But the essays I’ve been writing for the New York Times Magazine involve turning the appraising gaze inward. Often I use my own experiences to explain or inform how I view a particular subject, whether it be the building of a wall along the border with Mexico or the Trump administration’s executive order on immigration. I’m also now a columnist for the Nation, and that of course means building an argument while also advocating for a particular position or a given policy. But what all these forms of writing have in common, for me, is the imperative to place the subject within a very clear context for the reader and to be intellectually honest about it.

What sorts of things influence you when deciding whether or not to review a book?

Three things: time, contribution, ethics. I have to balance my writing and my teaching with all of my other commitments, so typically the first question for me is whether I have the time to read and think about the book thoroughly. The second question I ask myself is whether I have anything useful to contribute to the conversation about it. Would I be a good reader for this particular book? And the third question is: Can I be fair about it? I don’t do reviews if there’s an ethical conflict with the author, if we’re friends or colleagues.

You review both fiction and nonfiction. Do you have a preference for one over the other?

No. I really enjoy doing both because they’re so different and make me grow as a reader and as a person. When I review nonfiction I tend to do a lot of background research, which takes up a lot of time. With fiction I don’t need to do much research for the review, but I usually end up reading related things, like other books by the same writer.

Do you have a favorite book review you’ve written?

That is a tough question! I enjoyed writing about Salman Rushdie’s memoir Joseph Anton for the Nation. The review I heard the most about from readers—and still do, ten years later!—was a piece I did on Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Irshad Manji’s books, also for the Nation.

When you’re reviewing a new book from an author with previous books to his or her name, do you read the author’s backlist as well?

Oh yes. This is what I meant earlier when I said that I try to place the book in a clear context. I take note of the book’s literary antecedents, by which I mean works that might have informed it or influenced it. I also read the author’s previous books, to see how they might relate to the one under consideration.

You’ve reviewed graphic memoirs by Alison Bechdel, Marjane Satrapi, and Riad Sattouf. Can you reflect on the differences between reviewing this increasingly popular literary genre—work that is just as much visual as textual—and work that is entirely textual?

Comic books and graphic novels were a huge part of my life when I was growing up, so I’ve always had a soft spot for them. My husband has a significant comic book collection, so they’re always around the house. Still, I fear I am more limited in this genre because I don’t have visual arts training, and I try not to take on an assignment unless I’m really drawn to the subject matter.

Having published three works of fiction, you must know well the hopes and anxieties authors have about book reviews. How does it feel to be operating from the other side, as a critic?

It’s not easy. But I also know that the act of reading is by its nature biased: Each reader brings his or her own literary background and personal experiences to the act of interpretation. When I work on a review I try to keep in mind that my first responsibility is to readers: It’s my job to tell them about the book, what it has to say about the world, and how well I think it does this.

The literary industry and the literary media landscape have changed considerably since you began publishing. The detrimental effects are well chronicled; are there any changes you’ve noticed that you find positive?

It seems to me the entire landscape changes every five years. But I think one positive development is that the barriers for entry are a lot smaller now than they used to be. The literary conversation takes place mostly online, but anyone can set up social media accounts and instantly connect to other readers, writers, and critics. It’s never been easier to research agents or literary magazines or story contests than at the present moment. Unfortunately this hasn’t had much of an impact yet on the well-documented inequities in the publishing business. We need change there, too.

If you could change one thing about the book-reviewing process or the world of book criticism, what would it be?

I would love to see more effort and rigor in criticism of books by writers of color. There is a tendency, among certain critics, to treat writing by white writers as literature and writing by writers of color as ethnology. A lot of space is devoted to the scrupulous tallying of cultural detail and relatively little to literary choices made by the writer. I also wish that American critics would try to read a bit more world literature and literature in translation.

You’re active and quite popular on social media. How useful do you find it as a critic and as a writer?

As a writer I’ve found it to be a disturbingly effective procrastination tool. Never is the temptation to tweet stronger for me than when I’m on my second cup of coffee and it’s time to start working on my manuscript. A few years ago I bought software that blocks the Internet for up to eight hours, and I really don’t know what I would do without it. As a critic, though, I think social media can be quite dangerous. A place with so many opinions makes it hard to maintain independent thinking.

Which book critics, past or present, do you particularly admire?

So many. I came across the work of Edward Said and Chinua Achebe when I was in graduate school, and their criticism was at once a revelation and an inspiration for me. I’ve also learned a lot from Ngugı wa Thiong’o and James Baldwin. I still return to Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark because she’s so incredibly perceptive. Among the younger critics, I often read Parul Sehgal, Michael Gorra, and Pankaj Mishra.

What books that you aren’t reviewing are you most looking forward to reading in the near future?

I’m really excited about Zadie Smith’s new collection of essays, Feel Free. I really loved her previous book of essays. In fiction I’m looking forward to Denis Johnson’s The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, Tayari Jones’s An American Marriage, and Lauren Groff’s Florida.

Michael Taeckens has worked in the publishing business since 1995. He is a cofounder of Broadside: Expert Literary PR (broadsidepr.com).

Reviewers & Critics: Leigh Haber of O, the Oprah Magazine

Leigh Haber is the books editor at O, the Oprah Magazine, a position she has held for more than five years. She graduated from George Washington University with a degree in international affairs, and after getting a job as a copy aide at the Washington Post Book World, she worked for many years in book publishing, first in publicity and later as an editor—at Jeremy Tarcher, Ballantine Books, Avon, Bantam Books, Berkley Books, Harcourt Brace, Scribner, Hyperion, and Rodale—before turning to work as a freelance editor and start-up consultant. At O, the Oprah Magazine, Haber is responsible for putting together the Reading Room section of the magazine, and is always on the lookout for books to feature or excerpt elsewhere in the magazine. She also works with Oprah Winfrey and the rest of the staff to identify new candidates for Oprah’s Book Club. She can be followed on Twitter, @leighhaber.

You got your start in the literary world as a copy aide at the Washington Post Book World in the late 1970s. What was it like working there? Did it make you want to forge a path within the publishing world?

I arrived there not realizing there was an industry behind the books I loved reading—I’d never thought about it before. It was soon after Watergate, so the Post was a glamorous and iconic place, filled with characters. My first boss there was William McPherson, who’d just won the Pulitzer for criticism. He passed away last year, sadly, but that was a universe I am lucky to have glimpsed up close, and, yes, it did lead me to publishing.

You later worked in publicity for several years at Ballantine and Avon, and after that, in editorial for many years at Scribner, Hyperion, and Rodale and as a freelancer. How does your former experience as a publicist and editor inform your role today?

I am so steeped in the book world—it helps me stay on top of what’s coming out when, especially given that we work so far in advance, when there are no indicators of the reception a book will receive. Many of my book publishing colleagues—authors, editors, publishers, agents, publicists, media colleagues—I’ve known them for decades, which helps inform everything I do at O. But I like to try to approach the job itself as a reader, plain and simple. Do I love the book? Will our readers? And are we helping them to discover new talent or writers they’ve never read before, especially women writers? Are we finding books that will challenge or delight them? That’s our mission.

Who are some of the notable authors you worked with—and what are some notable projects you worked on—before you started at O?

When I was a publicity director I flew all over the place with a range of authors I now realize is absolutely astonishing, though at the time, being a mother of two boys, I was just trying to keep it all together. I worked with Alice Walker, Gloria Naylor, Umberto Eco, Charles Simic—and also Jimmy Buffett and Helen Hayes, to name a few who really stand out. I also worked on a tour with Mickey Mantle, which thrilled my dad. At Avon Books they were publishing lots of writers who were just gaining a literary reputation, including James Ellroy, Elmore Leonard, and John Edgar Wideman. But there I also worked with Rosemary Rogers. Those were incredibly fun days.

As an editor, I’m probably proudest of having acquired and edited Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth. But there are so many other writers I am honored to have worked with: Steve Martin, Jacqueline Novogratz, Jonathan Ames, Richard Hell, Tess Gallagher, Lou Reed, Glen David Gold, the Kitchen Sisters, Terry Gross, Bill Maher, the authors of The Intellectual Devotional, Scott Simon, Aasif Mandvi, Peter Jennings…

The literary coverage at O is quite expansive and varied. You oversee book reviews, book lists, excerpts, and original essays—anything else? How has your job evolved over the five years you’ve been there?

When I walked into this job more than five years ago, I’d never been a magazine editor. I didn’t know what I didn’t know, but my editors did. From them I’ve learned an entirely new skill. And I’m still learning. On the first day of my job I was told I needed to send some books to Oprah for book club consideration. I was frankly terrified. But then I read Twelve Tribes of Hattie by Ayana Mathis and I just felt it was a book Oprah would embrace. We’ve had six picks since then, and it’s always a thrill to know we are helping the authors to grow their audiences. Oprah’s passion for books is at the core of my job and always at the top of my mind. I consider it a privilege to assist her in bringing an entirely new dimension to a writer’s career. As far as Reading Room is concerned, I love that the support is there to be feminist, to be globalist, to be diverse, to cover poetry and literary fiction and emerging writers along with the established. And, yes, now I’m also helping to find essayists and contributors to the themed packages we do. How has it evolved? I will always recall this position as one that has to be occupied with a weird combination of humility and a kind of hubris. As to the hubris, I have to choose a few books to cover from the many worthy candidates, which means I have to trust my taste. Humility because I am always aware how lucky I am to be working on this platform, as a part of the incredible legacy Oprah has earned.

Walk me through what a typical week in the office is like for you.

We receive hundreds of books per week—probably two hundred a day. Sometimes it feels as if every day is Christmas, and other days I feel as if I’m drowning in books. And some of the books we receive make me wonder—is there really an audience for a topic this narrow and obscure? But every day I’m combing through the mail, opening packages, and trying to get a sense of the landscape. Most of the time my eyes are bigger than my stomach, and I bring home a bag bursting with books—I still read from the physical galleys. I have a beanbag chair in my office, and there are days when I am sitting in it, looking from my window overlooking Central Park from the 36th floor of the Hearst Building and thinking, “They’re paying me to read?”

I love envisioning the section every month with my editors and my partner in the art department, Jill Armus. There’s a lot of back-and-forth in terms of finding contributing writers, editing, revising, fitting, fact-checking, and so on. My favorite moment is when I see the section come together on page. The hardest times are when I’m working on the mammoth July Summer Reading package—eighteen pages instead of four. It’s tough trying to do something different and to get it right, but it’s exciting, too.

But it’s not all about books. We have a lot of conversations about a wide range of topics. Gayle King’s assistant is obsessed with Beyoncé. I’ve had to learn about her. You pretty much can’t survive in the O office without being a passionate pet lover, whether dogs or cats. You have to be willing to discuss your sex life, your therapist, how long you wear your favorite bra before washing it. It’s all fair game.

How many books do you typically receive per week—and of those, how many are you able to write about each month?

I would estimate we receive five hundred to seven hundred books a week. Of those, we can typically cover about fifteen a month.

Other than your interest in a particular author, what sorts of things, if any, influence you when choosing which titles to include—blurbs, prepub reviews, large advances, social media buzz? What about your relationships with publicists and editors—do those ever hold any sway?

I don’t view blurbs as helpful. They seem very quid pro quo to me. Raves in prepubs do sometimes alert me to books I need to take seriously. Advances don’t matter to me, and while I very much value my relationships with publicists, editors, and authors, it’s all about the read.

How conscientious are you about diversity—gender, race, sexual orientation, etcetera—when choosing what to include? And do you try to pay attention to books published outside of the Big Five publishers?

When I first started at O, I made a conscious effort to make the section and its contributors “diverse.” But I have to say that now happens organically. And all things being equal, if there’s a choice between a great book by a man and a great book by a woman, the woman wins.

O has been particularly inclusive of poetry over the years. Is poetry a special love of yours? Has it ever been difficult persuading editors to allow space for it?

I am not a poetry maven. I admire it, and I love reading it at times, but I don’t consider myself an expert by any means. I think it enriches our culture, and the section, so I go to others who know more about it than I do to teach me. My favorite was getting Bill Murray, who is a huge poetry fan, to tell us about five poems he loves—in person, at the Carlyle Hotel.

How many freelancers do you work with? Are there certain things you look for in a reviewer?

It’s just myself and an assistant on staff, so we do lean on freelancers. And while I have three or so regulars, I also like to have fun pairing a book with a reviewer. My favorite match-up was asking Mary Roach to review Ian McEwan’s novel in which the narrator was an unborn fetus. And I like to intermix big names with young new voices.

Is social media at all helpful to you in your role as a book editor?

I should use it more than I do in terms of promoting the Reading Room section, and I do try and follow what others are doing. Because Oprah.com is a separate entity, and O doesn’t have an online version, it’s hard to fully spread the word about how robust the section is.

What is the status of Oprah’s Book Club, and how does Oprah go about choosing which books to pick?

The book club is alive and well when we find the right book. The way it goes is that when I read for the section, I am always also thinking about what Oprah might like, either for the book club, or for some other purpose—film, movie, or just for pleasure. I send her books, and if something profoundly resonates, she will likely call me to tell me so. Then we talk about whether it could be a selection. We’d love for there to be picks on a more frequent basis, but that’s hard because the book has to be right and the timing for Oprah has to be right too. And of course, others are always sending books to Oprah—she’s not just hearing from me.

How have you seen the publishing world and the media landscape change over the past five years?

It seems indies and physical books are back. That’s cause for celebration. But print newspapers and magazines are, of course, facing challenging times, which means we have to keep innovating.

A frequent complaint in literary circles is that negative reviews take up space that could otherwise be used reviewing better books. Where do you stand on the value of publishing negative reviews?

I was told when I came to the magazine that we should pick books we think are worthy of coverage and share them with our readers. If we don’t like or love a book, we just won’t cover it. There are just too many good books to celebrate to devote space to the ones we don’t like.

Of those publications that still devote space to literary criticism, which are your favorites? Are there any book critics whose work you particularly enjoy?

I’m really going to miss Michiko Kakutani and Jennifer Senior. We also lost Bob Minzesheimer to brain cancer last year. And as everyone knows, the day of the standalone newspaper book review section, except for the New YorkTimes Book Review, is gone. But I’m looking forward to seeing what emerges, because I do think books are as important and as vital as ever, and there are lots of wonderful voices out there writing about them.

Name three books you’ve read in the past year that really knocked your socks off.

It still amazes me that the right book in the right moment can blow your mind. I just reread Night by Elie Wiesel, as there is a new edition with a foreword by President Obama. All I can say is that it’s as heartbreaking and beautiful now as it was when I first read it years ago. Future Home of the Living God, the latest from Louise Erdrich, absolutely floored me. It felt as urgent as a punch to the gut. The Hate U Give made me hopeful. Angie Thomas channeled her righteous anger into something incredibly brave and new, and she’s giving young people all over the country the sense that, yes, someone feels as I do.

Michael Taeckens has worked in the publishing business since 1995. He is a cofounder of Broadside: Expert Literary PR.

Reviewers & Critics: Kevin Nguyen of GQ

Kevin Nguyen is the digital deputy editor of GQ, where he writes about books, music, and popular media. He grew up outside of Boston in the 1990s and attended the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington. Since moving to New York City five years ago, he has run the Best Books of the Month feature at Amazon and was editorial director at Oyster, “the Netflix for books,” then Google Play Books after the tech giant acquired Oyster in 2015. He can be followed on Twitter, @knguyen.

At GQ you mostly work on reported features, but you also compile a Best Books of the Month feature. How many books do you receive each month, and of those how many are typically included in your roundups?

I went on vacation last week and returned to four mail crates of unopened galleys. So I’m getting something in the vicinity of fifty to seventy-five books a week. And honestly, I wish publishers wouldn’t send me things unsolicited. Most of those books are never going to be touched, and eventually they are shipped off to Housing Works for donation. In a given month I’ll try roughly twenty books. From those I’ll finish about half, maybe slightly more. And then I’ll pick about half of those—so it’s somewhere between four and six books each month. It really depends on how strong that month is.

In an ideal world, I would just request those books and not receive any mail. It feels like such a waste, but once you’re on those distribution lists, there’s no getting off them.

It’s funny. If I died today, the books would keep coming to the office, and I think about the poor person who would get stuck dealing with several thousand pounds of galleys each month. Which is why I plan to never die.

What sorts of things, if any, influence you when choosing which titles to include: blurbs, pre-pub reviews, large advances, social media buzz? What about your relationships with publicists and editors—do those ever hold any sway?

I keep a very long spreadsheet of books that are coming out, based on a combination of catalogs, publicist and editor pitches, Kirkus, previews from places like the Millions, and of course, word of mouth. Twitter can be a good signal, but its taste is fairly narrow.

I do read a lot of stuff blind, too. My equivalent of digging through the slush pile is browsing through everything available as a digital galley on Edelweiss.

Blurbs mean nothing. Same with big advances. Honestly, by the time the galley rolls around I’ve forgotten what I read about it in Publishers Lunch. I’ve been doing this for [checks watch], oh, Jesus, nearly seven years now. But I’ve got a system that works.

How conscientious are you about diversity—gender, race, sexual orientation, and so on—when choosing what to include? And do you try to pay attention to books published outside of the Big Five publishers?

Most people won’t cop to this, but I pay pretty close attention to making sure my list is inclusive. That spreadsheet I was talking about has a column that denotes if an author is a woman or a person of color, so I can make sure that there’s never a month when I am reading only white dudes. It feels weird—I am literally checking boxes—but it’s also a way to keep me honest.

On the upside, usually what I gravitate toward in terms of stories tends to be inherently diverse. You read enough and you see that a lot of books by white authors suffer from a kind of maddening sameness—thankfully you can identify this from the first fifty or so pages, if not sooner. Publishing has made slow strides forward in putting out books by people of color. Big lead titles are more diverse than ever.

And, of course, that spreadsheet also lists publishers. I make sure to read across the Big Five and indies each month. It’s probably the most useful column I have. Penguin Random House controls over 50 percent of trade publishing, and you could easily make the mistake of reviewing exclusively their books.

You’ve also edited some excellent literary features at GQ—Kima Jones’s interview with Colson Whitehead and Alex Shephard’s piece on Jonathan Safran Foer, to name just two examples. What goes into these features? Are you conceiving of them? Do you have much leeway when it comes to assigning literary coverage at GQ?

Both of those stories were my idea. Since we’re not a book-specific outfit, we have to find a story deeper than “this is a new book.” It has to speak to a broader audience, and that restraint had led to better pieces, in my opinion.

Kima and Alex did a great job with both, even though they were very different. Kima went deep with Colson Whitehead, and we were confident that the strength and reception of The Underground Railroad would justify going to such an intense place with the interview. For the Foer piece, it was a profile because we knew he was in an interesting inflection point in his career. Plus he surrendered some weird quotes about Natalie Portman. Love him or hate him, the guy is worth reading about.

You’ve written eloquently about the overwhelming whiteness in the U.S. literary culture and publishing industry. What critical steps do you think need to be made to diversify the literary ecosphere? In your recent Millions article you pointed out one bright spot of 2016: the momentous National Book Awards ceremony, so much of which was due to the National Book Foundation’s executive director, Lisa Lucas. Have you seen any other positive changes over the past couple of years?

As I mentioned earlier, publishing is a behemoth that is trudging along slowly in the direction of progress. But it still has a long way to go. Publishers used to excuse themselves by saying that the data showed books by people of color didn’t sell—a disingenuous claim. Well, in the past three years, we’ve seen some tremendously successful fiction by authors of color. So now editors and agents can’t say that anymore. Progress marches forward, and even the most reluctant figures have no choice but to be dragged along. I hope that in the next five or ten years, literary events will become spaces that are less oppressively white. I think we can get there.

You’ve had an interesting career path in the literary industry, with a notable stretch at the editorial side of Amazon, where you ran the Best Books of the Month feature. What was it like behind the scenes there? Did you and your team have full editorial control over which books you picked each month?

Amazon is bizarre, man! But the editorial team was—and still is—great. Real readers, with full editorial freedom. There was never any pressure to include or exclude anything, at least not in my time there. Remember that summer when Amazon was refusing to stock books from Hachette? It was one of the reasons I left the company. But one of the last Best of the Month lists I put together included Edan Lepucki’s California, a Hachette title we couldn’t even sell. Nobody at Amazon gave us a hard time about that, even when Stephen Colbert made that book a symbol against Amazon’s vicious business tactics. I don’t think Amazon is good for the world, but that editorial team is a bright spot in a bleak machine.

After Amazon you worked for two years at Oyster, an e-book streaming service billed as the “Netflix of books,” which was bought and later closed by Google Play. At Oyster you launched the Oyster Review, a remarkable online literary magazine that included reviews, interviews, essays, and book lists and featured an impressive roster of writers and critics. What went into creating and running that magazine?

A lot! Oh, man, but what a fun time. Basically, Oyster attempted to capture the indie bookstore feel and taste and personality in the digital space, as opposed to the big-box retail approach of Amazon. We hoped both could coexist, just like they do in brick-and-mortar.

The Oyster Review was the place where we’d establish our literary identity. Every great indie bookstore has one. And online, what you do instead of shelves and author events is publish reviews and essays and comics. I edited and art-directed the whole thing. And most people didn’t see this because it was in the Oyster app, but there was a whole mobile experience that had to be designed for too. So from conception to construction to day-to-day editing and production, I had a hand in all of it. And I loved doing it.

Obviously, it didn’t totally work out. But Google acquired the company, and one of the big selling points to them outside the engineering was the Oyster Review and all the fine editorial work we’d done. I’m very proud of that. I mean, has a tech company ever acquired a literary magazine before? It might be the first and last time that ever happens.

In addition to reviewing books and writing about literary culture, you’ve written widely about TV, movies, and gaming. Have your interests in fields outside of literature influenced and informed your literary criticism and vice versa?

Oh, definitely. You can tell the reviewers who do only books. There’s a strange stilted myopia there. I think the best writers have broader interests and can talk intelligently about other mediums.

Of those publications that still devote space to literary criticism, which are your favorites? Are there any book critics whose work you particularly enjoy?

Bookforum is probably the most complete publication out there. It has a strong perspective and tone and taste. Plus, the reviews are damn good. I wish they’d do a little more online so more people could see it.

I keep waiting for someone to start the Pitchfork of books, but every new book-related site that launches ends up feeling so flat and overly positive. Oh, and too damn white.

Name three books you’ve read in the past year that really knocked your socks off.

White Tears by Hari Kunzru by a mile. What a tremendous, smart, weird book. I tore through The Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann in a couple of days. And Ottessa Moshfegh’s short stories in Homesick for Another World have stayed with me in strange and surprising ways.

Michael Taeckens has worked in publishing since 1995. He is a literary publicist and cofounder of Broadside PR.

Reviewers & Critics: Dwight Garner of the New York Times

Dwight Garner is one of the most beloved book critics writing today. His New York Times reviews, whether positive, negative, or mixed, are always entertaining—not an adjective most would use to describe book criticism. Language comes alive in his reviews; one gets the sense that he’s playing with words and having fun along the way.

Raised in West Virginia and Naples, Florida, Garner started writing for alternative weeklies such as the Village Voice and the Boston Phoenix after graduating from Middlebury College. In 1995 he became the founding books editor of Salon, where he worked for three years, followed by a decade as senior editor at the New York Times Book Review. He has been a daily book critic for the New York Times since 2008. The author of an art book, Read Me: A Century of Classic American Book Advertisements (Ecco, 2009), he is currently working on a biography of James Agee. You can follow him on Twitter, @DwightGarner.

Raised in West Virginia and Naples, Florida, Garner started writing for alternative weeklies such as the Village Voice and the Boston Phoenix after graduating from Middlebury College. In 1995 he became the founding books editor of Salon, where he worked for three years, followed by a decade as senior editor at the New York Times Book Review. He has been a daily book critic for the New York Times since 2008. The author of an art book, Read Me: A Century of Classic American Book Advertisements (Ecco, 2009), he is currently working on a biography of James Agee. You can follow him on Twitter, @DwightGarner.

With Goodreads, Amazon, and countless blogs, it seems like everyone’s a book critic these days. What credentials do critics have that make them critics? And what was your own path to becoming a professional book critic?

No credentials are required to write criticism: Either your voice has authority or it doesn’t. Either it has style and wit or it doesn’t. Thank God there’s no grad program, no Columbia School of Criticism. Nearly all the best critics are to some degree autodidacts. Their universities are coffee shops and tables covered with books.

I grew up in a house that didn’t have many books in it, beyond the Bible and Reader’s Digest Condensed Books, at any rate, and where culture wasn’t particularly valued. I loved reading critics—book critics, movie critics, rock critics—from the time I was young. They gave me someone to talk to, in my mind, about the things I cared about. I’m the kind of reader who’s always flipped first to the “back of the book” of magazines, or to the arts pages of any newspaper. I worked in a record store during high school and wrote rock reviews for the school newspaper. This makes me sound almost cool; I was not almost cool. I was also the editor of my college paper. But I prefered writing book reviews, which I also did. Writing book criticism seemed to me then, and seems to me now, a chance to talk about everything that matters—the whole world, really.

You can’t trust Amazon reviews; I’m less certain about Goodreads, which I don’t know enough about. I’ve found it to be a terrific resource for certain kinds of information. Good writing is good writing wherever it appears, definitely including blogs. The more voices the merrier.

Facebook and Twitter have been a terrific boost to authors and publishers. Has social media aided your role as a critic?

I forget who it was who said that Facebook is a smart service for simple people while Twitter is a simple service for smart people. Ouch, right? But true enough. Twitter is companionable if you follow the right people, and you can dip into real-time conversations about books. You can see what people are saying; you can glean links to reviews. If people I respect are talking about a book, and it’s not on my radar, I’ll put it on my radar. I’ve reviewed books because I’ve seen interesting people talking about them.

Does buzz—a big advance or an author’s name—influence you?

Buzz matters and it doesn’t matter. Occasionally you might weigh in on a book because you have something to add about something everyone is talking about, perhaps to deflate the hype. Book critics envy movie critics only in that movie critics write weekly about things people are talking about and are likely to see.

Are you able to select which books you review or are they assigned to you? If you have a relationship with a publicist or editor, does it tip the balance?

At the Times we pick our own books. The daily books editor, Rachel Saltz, is a mensch, though, and is great at suggesting things. I review six or seven books a month; my schedule is two reviews one week, one the next. It’s about [equivalent to] the schedule of a major-league pitcher. Two or three of those books I know almost on contact that I want to review, because I’m interested in the author or I’m interested in the topic. After that, it gets headache-making. I sit down once a week or so with a big pile of galleys and poke around in them, looking for signs of life.

Relationships with publicists and editors (I don’t have many of those) don’t matter, either—a book is worthwhile or it isn’t, and the good ones know that. Having said that, a really good editor or publicist will know that very rare occasion to send up the bat signal, to indicate that a genuinely extraordinary book is on the horizon. Alas, even the bat signal, three times out of five, turns out to be hype.

Given the inordinate amount of review copies you must receive daily—just how many do you receive on an average day?—it seems like an e-reader would possibly help lighten the load. But the allure of physical books—even with galleys—is so hard to resist, isn’t it?

I get twenty-five to thirty books a day, and they really pile up on the porch. Last summer an elderly woman heard our three dogs barking—the windows were open, and we were out—and she saw the huge, sloppy pile of mail out front. She knocked on our neighbor’s door and asked, “Do you think the person who lives there is dead?”

I read e-books sometimes, mostly on my phone, but I don’t like to review from them. I write all over my books, I really mark the shit out of them, and I’m not confident that the notes I take on, say, a Kindle, will be recoverable in ten years. They’ll vanish, like the e-mail messages or the photos you meant to save from the laptop you owned three laptops back. So give me the dead-tree edition. I suspect I’ll always feel this way. Oddly, I do prefer to read magazines now on my phone or laptop. I find it easier on the eyes.

Have you ever changed your mind about a book that you praised or panned years earlier?

I deeply regret one or two reviews I’ve written. I was too hard, once, on a writer with a first book out; I still mope about my arrogance. These are the kind of reviews I’ve heard described as, “You know that thing you’ve never heard of? It sucks.” I regret a few raves, too—times when I’ve gotten carried away. I want readers to trust what I have to say on an intergalactic level but also on a bank-card level. Books aren’t cheap. I don’t want thousands of people walking around thinking they’d like to dun me for $26.95.

When you’re reviewing a new book from an author with previous books to his or her name, do you read the author’s backlist as well?

Very nearly always. It matters especially with fiction. I recently read the first three volumes of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle in just a few days. Each is five hundred pages or so. It felt like I was back in college, cramming for an exam. But those are beautiful books, and I feel lucky to have been able to submerge myself in them. It was like having a lovely fever.

Negative reviews: Do they have a purpose and a place? When a review is mostly a summary with nary a positive or negative opinion in sight, is that essentially a kind version of a negative review?

I hate summary reviews, unless the critic is very knowlegable about the topic and is sort of touring it for you. It’s among my goals as a critic to rarely if ever write one. You can’t trust a critic who doesn’t write negative reviews. Most books simply aren’t that good. I try to find things to admire even in books I don’t like, and I try not to be punitive and to have a sense of humor. But what’s a critic for if not to think clearly, make fine discriminations, and speak plainly?

There’s been a lot of talk within book-critic circles about the VIDA Count and calls for more racial and cultural diversity. Do you take this into consideration when deciding what books to review?

I try not to think about it. I try to pluck the books I most want to review, and hope that my interests are not so unlike everyone else’s that the mix will be a genuine mix. But it’s always in the back of the mind. It matters.

If you could change one thing about the book-reviewing process or the world of book criticism, what would it be?

I wish more young novelists wrote criticism, or at least kept a hand in. Some do, but fewer than in generations past. Doing so used to be part of being in the guild. I discovered a lot of novelists through their criticism. Now everyone plays nice, at least in print, and it gets dull.

What books that you aren’t reviewing are you most looking forward to reading in the near future?

The notion of reading for pleasure versus reading for work doesn’t have much meaning for me—it’s always both. But when I’m off duty, I most often find myself poking around in cookbooks. I thought my wife and I owned a lot of them; we have eight hundred or so. Then I met Nathan Myhrvold, who has fifteen thousand! I guess if you’re that wealthy it’s easier to be a collector.

I also like to read poetry and things like old collections of rock writing. Robert Christgau’s record guides from the seventies, eighties, and nineties are devilishly funny, and I find all kinds of things I want to listen to in them. I’ve heard that Christgau is writing a memoir. There’s a book I’m looking forward to. Put me down for that.

Michael Taeckens has worked in the publishing business since 1995, most recently at Graywolf Press and Algonquin Books. His website is michaeltaeckenspr.com.

Reviewers & Critics: Isaac Fitzgerald of BuzzFeed Books

In late 2013 Isaac Fitzgerald was selected to lead BuzzFeed’s new Books section, which has seen tremendous growth under his leadership. Doubtless one of the reasons BuzzFeed solicited Fitzgerald was for his excellent work as the managing editor at the Rumpus, where over a period of four years he published essays by many contemporary writers, including former Reviewers & Critics subject Roxane Gay.

These days Fitzgerald is a familiar figure in the New York City literary-events scene, having interviewed and moderated panels with a number of debut and established authors alike. This past spring, for instance, he led a discussion with authors Stephen King and his son Owen, and Peter Straub and his daughter, Emma, at St. Francis College in Brooklyn, New York. Fitzgerald has written for the Bold Italic, McSweeney’s, Mother Jones, and the San Francisco Chronicle, and is the cofounder of Pen & Ink and coeditor of Pen & Ink: Tattoos and the Stories Behind Them.

You were recruited to lead BuzzFeed Books a couple of years ago. Around that time you mentioned in an interview with Poynter that you were establishing a positive-only book-review policy, which caused a flurry of reactions from, among others, the New York Times, the New Yorker, Gawker, and NPR. Do you still stand by your decision?

Most definitely. Since I was brought on in December 2013, my goal has been to be the friend who’s always grabbing your shirtsleeve and saying, “Hey, this is what you should read next.”

The books conversation on the Internet is huge—that’s a wonderful thing! In that line you mentioned from my conversation with Poynter, all I was saying was that my little corner of the books Internet was going to be a fun and positive place. Which I’m proud to say is what we’ve accomplished.

I’m always thinking of larger audiences, of course, but in some ways it’s a really personal project. I think about the dirtbag kid I was, growing up poor in rural Massachusetts. If it weren’t for my parents, who love literature, I don’t know how I would have gotten into books. We weren’t supposed to love books—they didn’t seem cool, interesting, or relevant to our lives—and books weren’t supposed to love us. The world of books felt distant, something that was for other people. Not us.

So I got lucky. I got to fall in love with books. But I just as easily could have not, so it’s important to me that I use my tools and resources to make BuzzFeed Books great, not only for writers and critics, but for all the readers who might have been left out before. To use the wide reach and sense of connection enabled by the Internet to foster a love of books.

I wonder if part of the negative response to your “positive-only” intention was led by people thinking you were primarily going to feature reviews of books. But you’re featuring books in a variety of ways other than reviews. Was that your plan from the beginning?

The craziest thing about the whole experience was that it all happened before I had even shown up for my first day at work. There wasn’t really a plan yet. When I first showed up at BuzzFeed, it became abundantly clear that I had heaps to learn from my coworkers. Then, and even more so now, it was a totally staggering Avengers-team of a cohort—all these people with incredible skills in their wide-ranging areas of expertise. Design! Editorial! Tech! Video! There were so many possibilities for BuzzFeed Books, a wild array of options I hadn’t considered or had available to me before.