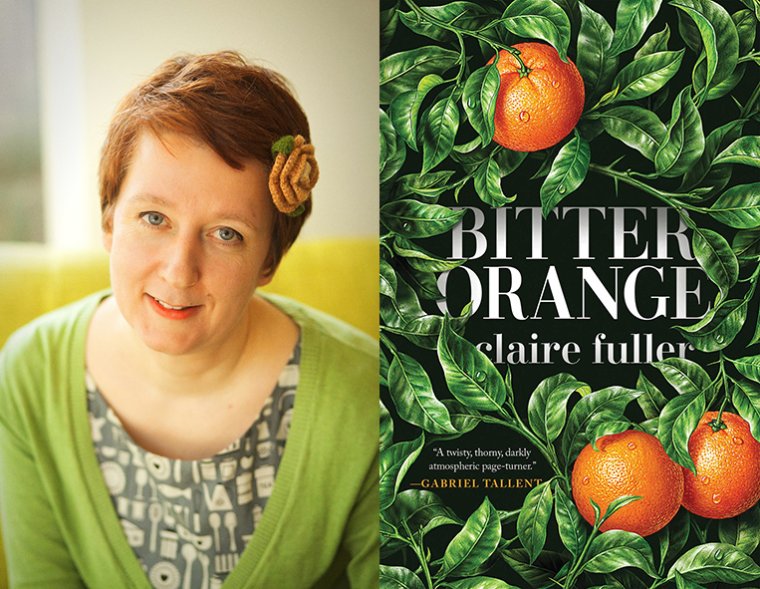

“It was an attempt to see if language can really be a bridge, as it is often aspired to be, and ultimately that it could fail.” In this video, Ocean Vuong speaks about the letter he wrote to his illiterate mother that inspired his debut novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (Penguin Press, 2019). A profile of Vuong by Rigoberto González appears in the July/August issue of Poets & Writers Magazine.

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous

Emilie Pine

Emilie Pine talks about fear of failure, connecting to readers, being open about grief and loss, and the power of storytelling with Ireland Unfiltered’s Dion Fanning. Pine’s debut essay collection, Notes to Self (Dial Press, 2019), is featured in Page One in the July/August issue of Poets & Writers Magazine.

Four Lunches and a Breakfast: What I Learned About the Book Business While Breaking Bread With Five Hungry Agents

If you want to learn about the business of books, it helps to be hungry. Not only hungry to learn, as the expression goes, but also just plain hungry, literally—it helps to have an appetite. Or an expense account. Ideally both. Because no matter how much the world of publishing has changed over the past hundred years—and, boy, has it changed since the days of Blanche Knopf, Horace Liveright, and Bennett Cerf—some things remain the same. It is still a business of relationships; it still relies on the professional connections among authors and agents and editors and the mighty web of alliances that help bring a work of literature out of the mind of the writer and onto readers’ screens and shelves. And those relationships are often sparked, deepened, and sustained during that still-sacred rite: the publishing lunch.

In the two decades I’ve worked at this magazine, I’ve had the pleasure of eating lunch with a small crowd of publishing professionals—mostly book editors and publicists, the majority of whom want to tell me more about a new book they have coming out, or an exciting debut author I may not have heard about and who would be perfect for a little extra coverage. I’ve always considered it one of the perks of my job to receive such invitations, because without exception they have come from kind, passionate, smart people—in short, ideal lunch companions. But until recently relatively few have been agents. There was a lovely meal in Chicago with agents Jeff Kleinman and Renée Zuckerbrot. And last fall, quite out of the blue, the legendary agent Al Zuckerman, founder of Writers House and agent to Ken Follett, Michael Lewis, Olivia Goldsmith, Nora Roberts, and Stephen Hawking, invited me to lunch at the Belgian Beer Café, which is now closed but had clearly offered Zuckerman, whose office is a short stroll away, in Manhattan’s Flatiron District, years of sustenance. Those lunches notwithstanding, I have not had as many opportunities as I’d like to sit down with agents and talk about the important work they do.

“According to the hallowed tradition of book publishing, it was necessary to have lunch with all these people, and many more, as often as possible,” wrote Michael Korda, the former editor in chief of Simon & Schuster, in his book Another Life: A Memoir of Other People (Random House, 1999), a treasury of anecdotes about the publishing industry in the mid-twentieth century. He goes on to paint a picture of publishing that has changed little, except perhaps the size of editors’ expense accounts:

For editors, in fact, having lunch is regarded as a positive, income-generating, aggressive act, and a certain suspicion is extended toward those few who can be found eating a sandwich at their desk more than once or twice a week. Publishers have been known to roam through the editorial department at lunchtime to catch editors who are ‘not doing their job’ in the act of unwrapping a tuna sandwich from the nearest deli. A large expense account is very often perceived as proof of ambition and hard work…. Nobody has ever done a poll to see whether the agents—the putative beneficiaries of this largesse—really want to be taken out to lunch every day of the workweek. It is simply one of the basic assumptions of book publishing that he or she who lunches with the most agents gets the most books.

To be honest, most afternoons I can be found in my office, staring over a sad desk lunch and trying to clear a heavy plate of work, not food. Meanwhile I suspect New York publishing’s best and brightest are rushing off to lunch reservations at fancy restaurants all over Manhattan, laying the groundwork for book deals and discussing plans for book launches and, yes, gossiping about titles the average reader won’t discover for many months or, more likely, years. To writers this world can seem opaque, removed from the solitary task of writing. So I figured it was time to get out of the office. It was time to learn more about how agents find writers and turn them into authors, to collect some honest advice for those who are looking for, or working with, an agent. And what better place to do that than in the agent’s native habitat: loud Manhattan restaurants.

The plan was simple: In five days invite five agents to lunch. (What did Robert Burns write about the best-laid plans of mice and men?) I asked each of them to pick a restaurant, ideally one they frequented with book editors and/or clients, and in exchange for a few hours of their valuable time, I’d pick up the check. Not surprising, all five chose restaurants in Manhattan—still the undisputed center of commercial book publishing—but thankfully not all were located in Midtown, that area between 34th and 59th Streets, where the concrete canyons can start to feel stifling to even the most urbane of urbanites.

I had previously met only two of the five agents I chose for this project. I was introduced to Anjali Singh of Pande Literary at a writers conference a couple years ago, and Emily Forland of Brandt & Hochman appeared in a cover feature, “The Game Changers,” in the July/August 2011 issue of this magazine. But for the most part, I didn’t know these agents, at least not well. I’d never met Julia Kardon of HSG Agency, Kent Wolf of the Friedrich Agency, or Marya Spence of Janklow & Nesbit Associates. I’d simply heard their names in casual conversation with editors and other agents, in the way one hears names when one talks about who is publishing what, when, and with whom.

All five of the agents represent authors whose recent publishing stories I suspected would illuminate certain aspects of the business—some positive, others maybe less so. I had no specific agenda for the conversations beyond eating some decent food and learning as much as I could about agents as people, their incentives for doing what they do, and how they see their role in the grand, flawed, beautiful experiment that is twenty-first-century book publishing.

MONDAY 8:45 AM

Kirsh Bakery & Kitchen

551 Amsterdam Avenue, near West 87th Street

Two eggs, scrambled; potatoes; toast; side of lox

French toast with marscapone cream and mixed berry jam

Three caffe lattes

Best-laid plans indeed. The first interview I am able to set up takes place not over lunch, as I had planned, but rather over breakfast because Anjali Singh’s schedule proves more crowded than a Times Square subway platform, which I thankfully avoid on my way to Kirsh Bakery & Kitchen on the Upper West Side. A few days earlier Anjali returned from the Belize Writers’ Conference, where she spent a week meeting with about a dozen writers from all over the United States who had traveled to the tropical locale to talk with agents about their writing projects. She came home to a full house: She has two children, ages ten and seven; her husband is a professor of Chinese history at Lehman College in the Bronx. Tomorrow she’ll travel to Selinsgrove, Pennsylvania, where she is scheduled to give a Q&A and talk with students in the undergraduate writing program at Susquehanna University. Such is the busy schedule of a literary agent. So, yes, breakfast it is.

Anjali spends the first ten minutes of our time together recounting in remarkable detail the writers she met in Belize, all of them women—a retired fire chief from California; a police detective from Omaha; a speech pathologist from Reno, Nevada—and the way she speaks about these writers, with excitement and genuine interest in not only their writing, but also their personal and professional lives, provides a caffeine-fueled preview of what’s to come in our conversation. While most people would rhapsodize about the Caribbean shoreline or the daily yoga sessions that I will later learn were part of the conference schedule, Anjali’s takeaways are the lives of writers whose paths she feels fortunate to have crossed. “It was a beautiful beach and everything, but the best part was the writers I met,” she says. “It was amazing. It was so good for my soul.”

Anjali’s career in publishing started in 1996 when she took a job as a literary scout with Mary Anne Thompson Associates, having graduated from Brown University with a degree in English and American literature. I’ve always been curious about literary scouts, or book scouts as they are sometimes called, and wanted to know more about what these “spies of the literary world,” as Anjali jokingly calls them, actually do. “So you’re basically a consultant,” she offers helpfully. “You get paid a monthly retainer by your clients, and your clients are foreign publishers. But you only work for one per country because otherwise it would be a conflict of interest. When I first started, of course, there was no Publishers Marketplace or Deal of the Day or any of that. It was all on the ground. Mary Anne would talk to her editor friends…and then, officially, I would talk to agents. I covered certain agencies, and I would call them and find out what was going on and what books had sold to whom for how much. We would do a report every Friday, like a deal memo, and it would say, ‘XXXXX publisher, you should pay attention to this.’ So the idea is to help them get ahead of their competitors, or to be on par with their competitors, to get books early. It’s to be their eyes and ears in the New York publishing world.”

Anjali tells me that Mary Anne Thompson had exclusive contracts with foreign publishers such as Macmillan in the U.K., Droemer Knaur in Germany, and Kadokawa Shoten in Japan. Nowadays, with so much information available online, the scout’s job is to filter that information and tell the clients what to pay attention to and what to disregard, “because you can’t possibly pay attention to everything,” she says.

In some ways it was the ideal first job in publishing, working for five years in a small office, learning about the business alongside colleagues who would also go on to successful agenting careers, including PJ Mark, now an agent at Janklow & Nesbit; Cecile Barendsma, who has her own agency in Brooklyn; and Susan Hobson, director of international rights at McCormick Literary. “What it allowed me was an incredible database of information about publishing,” Anjali says.

But this information couldn’t have prepared her for the vagaries of the next dozen or so years, during which she moved from one house to the next—not uncommon for editors coming up in the business. First she was an editor at Vintage, the paperback imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, and she very quickly made a name for herself by discovering Persepolis, the best-selling graphic memoir by Marjane Satrapi, on a shelf at a friend’s apartment in France, where the book was originally published. Anjali brought it to the United States, and it was published to great acclaim by Pantheon, another Knopf Doubleday imprint known for publishing graphic classics such as Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth.

Anjali worked at Vintage for four years, buying paperback rights to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s debut novel, Purple Hibiscus, and working on her second, Half of a Yellow Sun, before leaving to go to Houghton Mifflin (later Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), hired as senior editor by vice president and publisher Janet Silver. Silver was later let go, about a year before Anjali herself was laid off, during the financial crisis of 2008, just after Anjali’s first child was born. Two years later, Jonathan Karp hired Anjali as senior editor at Simon & Schuster, but she remained there for only two years before she was laid off during a restructuring in which Free Press, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, was folded into the company’s flagship imprint.

Her next stop was Other Press, an independent publisher of literary fiction and nonfiction founded by Judith Gurewich and Michael Moskowitz, where Anjali was editorial director. Although her stay at Other Press was relatively short—only sixteen months—it was a refreshing change after her years in the corporate environments of Vintage, Houghton Mifflin, and Simon & Schuster. At Other Press, she says, “I just got to feel a sense of stability again, and a sense of self-worth, I guess. I got to be much more connected to what made me care about books and publishing.”

Shortly thereafter her husband got tenure—and the time and financial stability, not to mention health insurance, that comes with it—so she made the switch to agenting. She’s been at Pande Literary for three and a half years.

Which is where Arif Anwar and his debut novel, The Storm, enter the conversation. Before Anjali became an agent, Arif had queried Ayesha Pande, head of the eponymous agency, with the manuscript of a novel that told a half century of Bangladeshi history through the braided stories of characters who live through a storm similar to the 1970 Bhola cyclone, in which a half million people in East Pakistan and India’s West Bengal died overnight. Ayesha had offered representation, but Arif went with another agent who had offered her services first.

Two years later, Anjali was now an agent and Arif was looking for a little more hands-on attention, so he asked again whether Ayesha was interested in representing him. Ayesha and Anjali both read his manuscript, compared notes, and decided that they would take him on, with Anjali assigned to do the editorial work necessary to prepare the novel for submission.

“One of the things that I found really moving was that he depicts a fishing community in Bangladesh,” Anjali says about Arif, who was born in Chittagong, a port city on the southeastern coast of Bangladesh, and now lives in Toronto. “There have been other books, but not that much South Asian literature focuses on the underclass—those people who aren’t visible. He just immediately brought me into this world in a very visceral way. It’s really ambitious, and I admire that ambition. He’s also writing outside of his experiences, writing from the perspective of a British nurse in the 1940s, and a Japanese fighter pilot. I admire the scope of that vision.”

Anjali worked with Arif for roughly six months, cutting two whole narrative threads from the manuscript and weaving together the remaining five. Finally it was ready to be submitted to editors. Because Arif lives in Toronto, Anjali says, it made sense to have a separate Canadian publisher. After an auction involving three excited editors—notable, given the relatively small Canadian market—the book went to Iris Tupholme at HarperCollins Canada.

Reactions to submissions in the United States were less encouraging. “We got a lot of passes, which was devastating,” Anjali says. “A lot of passes, including from someone who really liked the book but after talking about it with her publisher was like, ‘We can’t do this because we have another book with a Bangladeshi character.’ The author wasn’t Bangladeshi, but it was about a Bangladeshi woman.”

Anecdotes like this one, that throw into relief the cold reality of publishing as a subjective business that is not always all about the writing, have clearly made Anjali more determined than ever to use her role as an agent to fight for greater access on behalf of her authors. “A hunger to see more stories, to tell different stories in different places in the world,” she says about her own agenda. “A hunger for representation across class, which I think literary fiction doesn’t always do that well. All of that I’m bringing to the table.”

Eventually Rakesh Satyal of Atria Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, offered a deal in the United States, and Arif was off to the races. About four months ahead of publication—HarperCollins Canada scheduled it for March 2018, Atria set a May 2018 publication date—Anjali joined Arif on a conference call with the publicity team at Atria to brainstorm ideas for articles and essays Arif might write and try to place in newspapers, magazines, or websites to boost awareness of the book. Arif was also asked to supply Atria with names for a “big-mouth list” that might include organizations working with or interested in Bangladesh, as well as writers he admires.

“Big mouths” is an industry term for anyone—writers, editors, bloggers, and people with a large following on social media—in a position to spread the word about a book. These people are often on a list that the publicity department uses for a targeted mailing of finished copies of a book, sometimes accompanied by a personal note from the author or editor.

When I ask Anjali whether Arif was doing enough in the lead-up to publication, I don’t even have to finish my question. “Oh my God—the whole time Arif was like, ‘This is what I want to be doing. Tell me what I can do. I’ll do anything you want me to do.’” The book received starred reviews from Library Journal and Booklist as well as a rave from Publishers Weekly calling it an excellent debut: “This first novel will touch and astound readers.”

Still, momentum can be difficult to sustain, and while the novel received some terrific blurbs from authors such as best-selling author Shilpi Somaya Gowda and novelist Rumaan Alam, and a positive review in the New York Times Book Review, albeit two months after the publication date, it just didn’t quite reach the heights that Anjali and, certainly, Arif were hoping for. Everyone, of course, is hoping for a best-seller. “Some really nice things happened, like the reviews, which made us hope it was poised for more, but for whatever reason…we just never got a sense of momentum,” Anjali writes to me after our breakfast. “I think it was both a success in the fact that we found editors who championed this book and published it beautifully; Arif is now an ‘author’ with some lovely reviews under his belt, one who has begun to make meaningful connections with readers at book clubs and the various festivals he was invited to; and he now has a paperback to sell the hell out of. I think as the agent, along with Ayesha, and as someone who loved this book and who thinks if more people knew it existed it would have a stronger readership, it’s hard not to feel some small sense of disappointment that the book wasn’t a best-seller, even though I do know how hard that is to achieve. Our hope is that Arif’s career will continue to grow, and as it does, more readers will discover and fall in love with this book.”

I ask Anjali if she has any advice for writers looking for an agent, and she doesn’t hesitate. “The best thing you can do is be really intentional about who you approach,” she says. “It’s doing all that work to write a really good query letter. It’s also doing all that work to think about what books your book sits alongside. And who you aspire to be as a writer.” This will be a recurring theme as I talk to the agents—this idea of intentionality, of doing the work of figuring out who you are as a person, as a writer, and how you want to direct that out into the world before you approach agents. “There’s a reason why you spent all of these years writing this book. If you can explain to me why you cared so much, it’s going to help me understand why I should care. And I think that is a kind of self-knowledge. I feel like by the time you write that query letter, you have to excavate that and articulate it.”

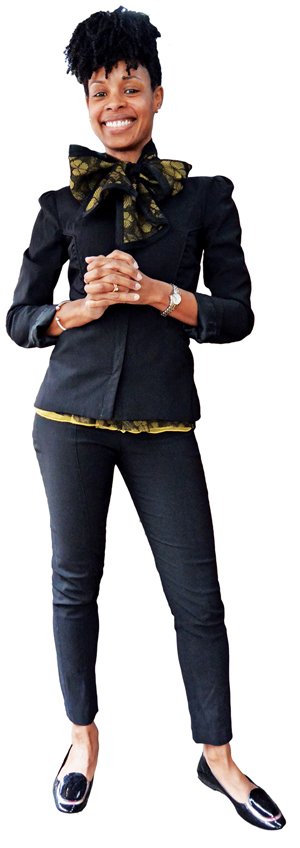

(Singh: Chuck Wooldridge)TUESDAY 12:30 PM

Russ & Daughters Cafe

127 Orchard Street

Whitefish Croquettes: smoked whitefish, potato, tartar sauce

Pickled Herring Trio: canapés of pickled herring on pumpernickel

Lower Sunny Side: eggs, sunny-side up; Gaspé nova smoked salmon, potato latkes

Challah bread pudding: dried apricots, caramel sauce; Halvah ice cream: halvah, sesame, salted caramel

Cream soda: vanilla bean–infused demerara sugar; Concord grape soda: jasmine, timut pepper, lemon

Making my way up Delancey Street, a few blocks from the sublet apartment where I laid my head during my first month in New York City—fresh out of an MFA program, little money, no prospects—I’m having difficulty matching the glass-encased condominium complex and the fancy Regal multiplex with my memory of the boarded-up storefronts and dirty brick facades of the Lower East Side in the late 1990s. But I don’t have a lot of time for nostalgia because I’m on my way to Russ & Daughters Cafe to meet Emily Forland, and she gave me explicit instructions to not be late. My punctuality has long been a point of pride, but I understand her urgency; the restaurant, which opened in 2014, on the hundredth anniversary of the original Russ & Daughters appetizing store, located two blocks away, on Houston Street, doesn’t take reservations. And it’s always busy. But Emily has called in a favor. She is the agent not of Joel Russ of Russ & Daughters (he died in 1961), nor his daughters (the last of them, Anne Russ Federman, died last year at the age of ninety-seven), but rather his grandson Mark Russ Federman, who wrote a memoir, Russ & Daughters: Reflections and Recipes From the House That Herring Built (Schocken, 2013), and whose daughter and nephew opened the restaurant to which I am headed posthaste.

I find Emily waiting a bit nervously in the small crowd outside (I’m not late), and we duck inside and are quickly ushered to our booth.

Originally from San Antonio, Texas, Emily moved to New York City to attend the MFA program in poetry at Sarah Lawrence College. Through a family friend (one of her father’s friends was married to Judith Rossner, author of Looking for Mr. Goodbar), she lucked out on an invitation to have dinner with Rossner’s literary agent, the much-beloved Wendy Weil. Nothing momentous happened at the dinner, but a couple of weeks later, she ran into Wendy on the subway. “She was coming from her weekly tennis game, and she looked like Annie Hall, and instead of being timid and hiding behind my New Yorker, which might have been what I normally did, I just went over and said hi. And we rode together.” In other words, it was one of those incredibly fortuitous moments when your life is forever altered by happenstance and a simple decision—like screwing up your courage and saying hi to a famous literary agent who you happened to see in the crowd.

Emily was offered a summer internship at the Wendy Weil Agency—the same summer, coincidently, that Wendy was interviewed for a profile that appeared in the September/October 1997 issue of this magazine—and continued on at the agency as an assistant and, eventually, as a full agent, up until when Wendy died suddenly, in September 2012. Emily then moved to Brandt & Hochman and represents authors such as Jane Alison, Flynn Berry, Katharine Dion, Carrie Fountain, Kirk Lynn, Elizabeth McKenzie, and Dominic Smith.

As the waiter brings us our whitefish croquettes, however, the author we are talking about is Nathan Hill, whose debut novel, The Nix, was the talk of the town—and, more important, bookstores—in 2016, when it was published by Knopf and landed on all the big year-end lists (the New York Times, Entertainment Weekly, the Washington Post, Slate). At last count the number of languages the novel has been published in was twenty-eight, but Emily tells me that this morning the agency’s foreign-rights director got a call from Beirut about an Arabic edition, so it might be twenty-nine by now.

The publication of The Nix is a lesson in perseverance and patience that pays off in a big way, the biggest way imaginable for most writers. It’s not just that the author took his time writing the book (ten years, from 2004 to 2014), and that he was patient through the publishing process (which took another two years), but also that he was patient in his professional relationship with Emily—after all, The Nix wasn’t even the first book of his that she had tried to sell.

Nathan first queried Emily (it was a “very straightforward” letter, she recalls) when she was still at the Wendy Weil Agency, in December 2010. Nathan had read Susanna Daniel’s novel Stiltsville, which was set in Florida, where he lived at the time, and decided to send her agent, Emily, a collection of stories he had written partly while an MFA student at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst six years earlier. “I wrote to him after reading the first few pages of the first piece,” Emily says. “The writing was so strong, and I told him I had to keep reading, but I already knew.”

Ask any agent and you’ll likely hear the same thing: Stories are hard to sell. So it’s a testament to Nathan’s talent that Emily fell so deeply for his writing that she was willing to send the collection of stories (“very interconnected, about a couple inching toward each other,” she says) out on submission in 2011. “It came close, but it didn’t land,” Emily says about response to the collection. “There were people who really admired it but couldn’t get it through, or thought, ‘Ugh, stories.’ Also, stories come in waves of editors being receptive to them.”

Rather than let this derail him, Nathan told Emily about a novel he’d been working on for the past six years, about a mother and her son, partially set in 1968, and secrets about the mother’s past. Intrigued, Emily took him out to lunch the next time he was in New York. The two dined at the Morgan Library, across from the Wendy Weil Agency. (Fun fact: At the end of The Nix, there is a scene set in the dining room of the Morgan that was drawn from this visit.) For two years afterward, the two kept in touch.

It’s worth slowing down for this part and considering: two years. After getting encouragement from Emily, he didn’t rush through a draft of his novel; he wasn’t despondent after the rejection of his stories or panicking that his window of opportunity was closing. He took the time to write the best book he could write. In the meantime Emily had moved to Brandt & Hochman, but eventually Nathan wrote to her again: “Okay, remember my novel?” Emily recalls him writing. “It’s now also about cell-phone distraction and Occupy Wall Street and multiplayer online games and the housing crisis. Are you still in?” After Emily assured him she was, another update would arrive every six to eight months.

“Nathan was canny because he waited,” Emily says. “When he finally delivered The Nix, he waited quite a while for me to read it.” Why is this important? Because the manuscript he delivered, in the summer of 2014, was 275,000 words. (Some math: the typical double-spaced manuscript page contains 250 words, which means this draft was roughly 1,100 pages, or more than two packages of standard printer paper.)

About six months of revising and editing between agent and author followed. “Every draft he gave me, he had worked very hard to get to and had specific questions but was also very open to feedback…just open and creative in the way he addressed comments and revision,” Emily says. “I think he really enjoyed being in this book, so I don’t think he was hurrying.”

Finally, after cutting 35,000 words and moving some sections around and pushing the manuscript as far as they could, Emily sent it out to editors, in advance of a blizzard, at the end of January 2015. She submitted it to twelve editors, and additional editors requested it after there was a “very noisy response from foreign publishers.” I ask Emily what this means. How could foreign publishers know about it? “I guess the scouts got it,” she says, meaning one of the editors she sent it to must have forwarded it to one of those “spies of the literary world,” as Anjali Singh had joked. This can be a good thing—it was a very good thing in this case; fire spreads—but it doesn’t always work out that way. “If you have a quiet literary novel that is going to find its way but might take a lot of submitting, it’s likely that it’s going to be old news by the time it’s gone out. You don’t want anything to be shopworn.” In other words the scouts can note a lack of enthusiasm, too.

But in this case the fire spread, and Emily was fielding requests to see the manuscript, including one from Tim O’Connell at Knopf, who was not one of the original editors to whom Emily submitted it but who nevertheless made a preemptive bid (or preempt, the purpose of which is to end a bidding war immediately by offering a significant advance). It worked. “Knopf was great,” Emily tells me. “They were really behind it, their offer was strong, and we got to keep foreign rights.” (Marianne Merola, the foreign-rights director at Brandt & Hochman quickly sold rights in fourteen countries, so that detail about the foreign rights turned out to be a very good business decision.)

Nathan and Tim did another round of edits, cutting an additional thirty thousand words or so. This work did not come as a surprise to Nathan; before accepting the offer from Knopf, he had spoken with Tim, who wanted to make sure he conveyed exactly what was expected of the process. Nathan was all in. “It was very much about making sure the novel was as compulsive as it could be,” Emily says about the final round of editing. Meanwhile the gears were starting to turn on the marketing and publicity side of the business as well. Early on, Nathan returned to New York and met with Emily and representatives from the publicity department at Knopf. Emily says she expected maybe four people at that meeting. The conference room was full.

The purpose of such a meeting is to brainstorm ideas and explore possible ways of getting the word out about the book in advance of publication, but it’s also an opportunity for the folks in publicity to meet the author and see for themselves what he’s like—his style, his personality, his communication skills—as arguably the most important spokesperson for the book. Despite not knowing the crowd of professionals in the room, he made an impression, especially with Knopf’s vice president and editorial director. “I just remember Robin Desser whispering in my ear as we were leaving, ‘He’s a rock star,’” Emily says.

Before it was published on August 30, 2016, The Nix landed a coveted spot on the Editors’ Buzz panel at BookExpo, held that year in Chicago. (BookExpo America, or BEA, is the country’s largest book trade fair, and it’s where editors, publishers, agents, and authors from around the world promote their forthcoming books to a captive audience of booksellers.) It was also reviewed in all the usual places, and Nathan was profiled in the New York Times four days before the book was published. A month later, Warner Bros. optioned the novel for a television series adaptation, with JJ Abrams set to direct. Meryl Streep was initially attached to the project but no longer; as of this writing it’s still being cast.

Hope for the best; expect the worst. If Emily had a pregame speech—something she told her authors before she sends their work out on submission—that would be it. “In general I think that stance is helpful for going through the world and especially going through the world as a writer,” she says. And sometimes, as Nathan Hill’s story illustrates, you work hard then hope for the best, and that’s pretty close to what you get.

THURSDAY 12:30 PM

Gaonnuri

1250 Broadway, 39th floor, corner of West 32nd Street

Black Cod Gui: white kimchi, chive, doenjang, gochujang, served with white rice, banchan, and seaweed soup

Marinated Galbi: marinated prime beef short rib, served with white rice, banchan, and seaweed soup

Walking into Gaonnuri, the posh Korean restaurant on the thirty-ninth floor of a skyscraper just south of the Empire State Building, I’m reminded of the first time I had the very New York experience of riding an elevator to what I assumed would be a hallway leading to the apartment where a cocktail party was in full swing, but when the elevator doors opened, I was staring at the inside of the apartment, and all the guests turned their heads and stared. For an introvert this is the stuff of nightmares. But the panoramic view of the Manhattan skyline that greets me this afternoon when I step off the elevator is something else entirely, and as I’m shown to a table by the windows, I do not resist the urge to snap a photo with my phone. Fortunately, Julia Kardon, an agent at Hannigan Salky Getzler (HSG) Agency, hasn’t yet arrived to witness my touristy act.

When Julia does arrive she tells me why lunches with editors are so important for agents. “You just learn things about them that you can’t learn from their Publishers Marketplace write-up. You find out that Emily Graff at Simon & Schuster has a twin sister. So then you might think about how you would pitch a book about siblings to her. Molly Turpin [at Random House] is a beautiful artist, so in addition to the kind of history, nonfiction, that she focuses on, if you have a project that has to do with art history, you would definitely want to send that to her.”

Born and raised in New York City, Julia studied comparative literature as well as Slavic languages and literature at the University of Chicago, then moved to Prague to teach English for a year. Back in New York, after a brief internship at the Wylie Agency, she started her career at Sterling Lord Literistic, where she was an assistant to Philippa (Flip) Brophy, who showed Julia the ropes, including the art of the phone pitch. “She was on the phone constantly. Her handset smelled like her perfume,” Julia recalls. “I learned from her, and that made me want to pitch that way.” In addition to e-mailing a pitch letter to editors, she adds, “I, unlike some of my millennial peers, always call editors to pitch a project.”

Julia worked at Sterling Lord for just under three years before moving to Mary Evans, a boutique agency (a fancy term for a small, specialized agency), where she worked on foreign rights while building a list of clients for herself before moving to HSG. Among the first clients she signed was John Freeman Gill, whom Julia reached out to after reading an op-ed he had written in the New York Times titled “The Folly of Saving What You Kill,” about preserving the city’s old buildings. His bio stated that he was working on a novel about architectural salvage. Intrigued, she invited him to lunch. “He knew that I was young, but the way you position yourself when you’re young is that you’re very hungry but you’ve also worked on great things, like ‘I’m working with Michael Chabon to some degree. I worked on James McBride’s National Book Award–winning novel,’ things like that. Obviously I didn’t agent it, but I know what the publishing process looks like. I know how it’s done and how it should be done.” In other words, there was some salesmanship involved, but the two connected, and she ended up selling his novel, The Gargoyle Hunters, at auction to Knopf.

I ask Julia how an auction works, specifically a round-robin-style auction like Gill’s, in which there were four bidders. “You send the auction rules to everyone, and basically you tell them what rights they’re bidding on. If you have a lot of attention, you’d want to make that North American rights only,” she says, and I remember Emily Forland’s smart decision to retain foreign rights for her big sale. Julia continues: “In the first round everyone makes their first bids, and then you call the lowest bidder and tell them what the highest bidder’s number was, and they have to become the new high bidder or they have to drop out. And then you call the next-lowest bidder and tell them what the new high bid is. And they have to beat that or they drop out. And it goes around like that. It can be pretty exasperating because sometimes the lowest bidder will improve the highest bid by $2,500 or $5,000. So you can go from $100,000 to $200,000 over the course of two days, and it’s like, ‘I’m going to lose my mind if I have to keep doing this.’”

To avoid a prolonged auction, agents sometimes dictate a minimum increment by which a bid can be raised. “You can also at any point in the auction call for best bids,” she adds. “Theoretically that is just getting everyone’s best, final bid, and you don’t go back to negotiate.” But agents can and often do go back to negotiate certain aspects of the agreement, such as the payout of the advance—traditionally a third at signing, a third when the publisher accepts the final manuscript, and a third on publication, but that can be adjusted to quarters, with the final 25 percent due on paperback publication. The agent’s standard cut is 15 percent of the author’s gross domestic earnings, including the advance (and 20 percent for foreign rights deals).

Writers often think of agents sitting in well-appointed offices and waiting for a query or proposal to strike their fancy. But the path to a literary agent is not a one-way street. Agents are actively looking for potential clients too. This is how Julia found John Freeman Gill, and it’s also how she found Brit Bennett when she was in her final year of the MFA program at the University of Michigan. On December 17, 2014, Jezebel published an essay by Brit titled “I Don’t Know What to Do With Good White People” that went viral. “As soon as that essay published, I knew that it was going to be big,” Julia says. “I think it was already at several hundred thousand page views by the time I read it. And I looked in the white pages to see if I could find her phone number and—I don’t remember doing this, but—I apparently left a voice mail on her mother’s answering machine in California. Brit says she was in a class, and her mom called her cell phone…so she ran out of the class to make sure everything was okay. ‘An agent just left a voice mail for you; I think it’s really important!’ I don’t remember doing that, but it’s not unlike me…. I knew that I wouldn’t be the only agent to reach out to her. I think nine ultimately did. And I wanted to make an impression by getting in early and showing her that I was really passionate, because at that point I hadn’t even had one of my client’s books published yet. Brit’s book was my first book to publish. It was not the first book I sold, but it was my first one to publish. So I didn’t have a lot that I felt like I could trade off of other than the power of my conviction and the passion that I had for her.”

When the two of them eventually talked, Julia asked Brit if she was working on an essay collection. When she learned Brit was actually writing a novel, The Mothers, about a seventeen-year-old whose pregnancy leads to a decision that shapes her life and the lives of those around her forever, Julia asked for the first chapter. “I read that chapter and I was like, ‘Holy shit. This is amazing.’ I felt like that immediate electricity coming off the page, sizzling in my hands, and I’m like, ‘Okay, where’s the rest?’” Four weeks later, when Brit sent the full manuscript, as she had requested, Julia cleared her schedule and read it the same day it arrived. She was so blown away by it that she called Brit that evening to tell her she loved it and thought she could sell it. “She was so funny because Brit is very reserved and very cool and collected as a person,” Julia says. “She just was like, ‘Oh, thank you so much for reading so quickly. Can we schedule a call to talk about this tomorrow? Right now is not good for me.’”

Julia figured Brit was fielding offers from other agents. “I just had to assume that almost everybody who had two eyes and a beating heart and a brain would be able to recognize very fast that this was an incredible talent.” She scheduled a call with Brit for the following morning and, at the appointed hour, made the case for why she should be Brit’s agent. It didn’t go very well. “I just felt really unsatisfied with the conversation. I hadn’t asked her enough questions,” Julia admits. “And I remember talking to Mary Evans’s assistant about whether or not I should call her back, because [Brit] isn’t here in New York, so I can’t take her to lunch and show her how cool I am and find out more about her.” After much deliberation Julia did call her back that same morning, and the two ended up talking for two more hours. Even after that Julia wasn’t confident. “I do remember that it was this agonizing stretch of time. I felt completely convinced that she wouldn’t sign with me but that I had done everything I could. So I could at least take some small comfort in that I was going after the right people.”

But Brit did choose Julia, and when Julia sent The Mothers out to editors, right before the 2015 London Book Fair, Sarah McGrath, vice president and editor in chief of Riverhead Books, put in a significant preempt that was too good to pass up. The novel was published in October 2016, quickly became a New York Times best-seller, and was named a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle’s John Leonard Award, the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize, and the New York Public Library Young Lions Fiction Award.

Julia and Brit’s relationship is a great success story, but it’s also a good reminder of the effort that agents often put into finding their authors. It also shows that the balance of power is not always weighted so heavily in the agent’s favor. While it may seem like agents hold all the cards, it’s important to remember that agents hope writers will choose them, too.

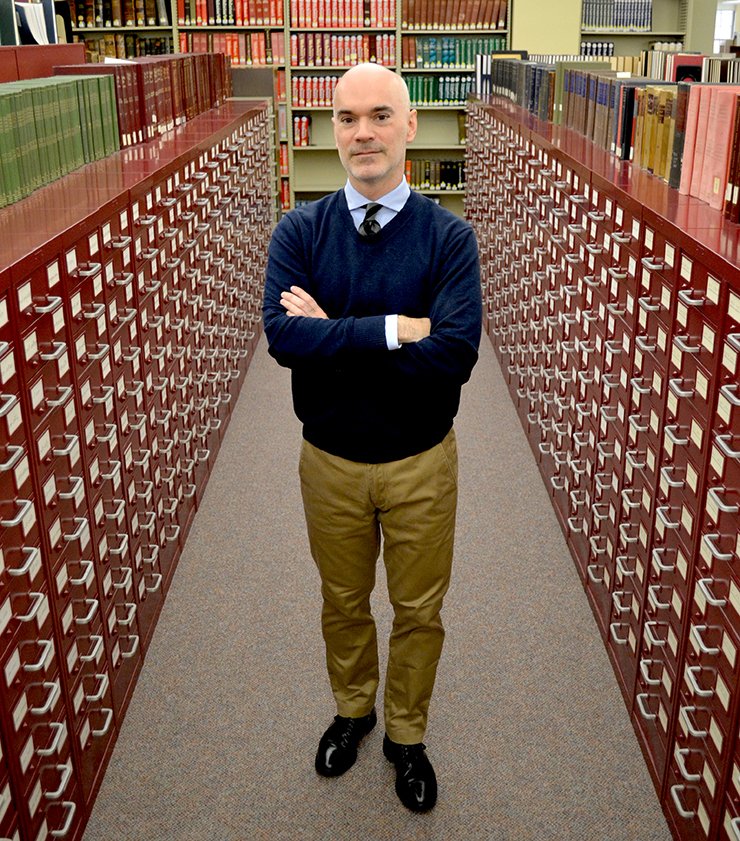

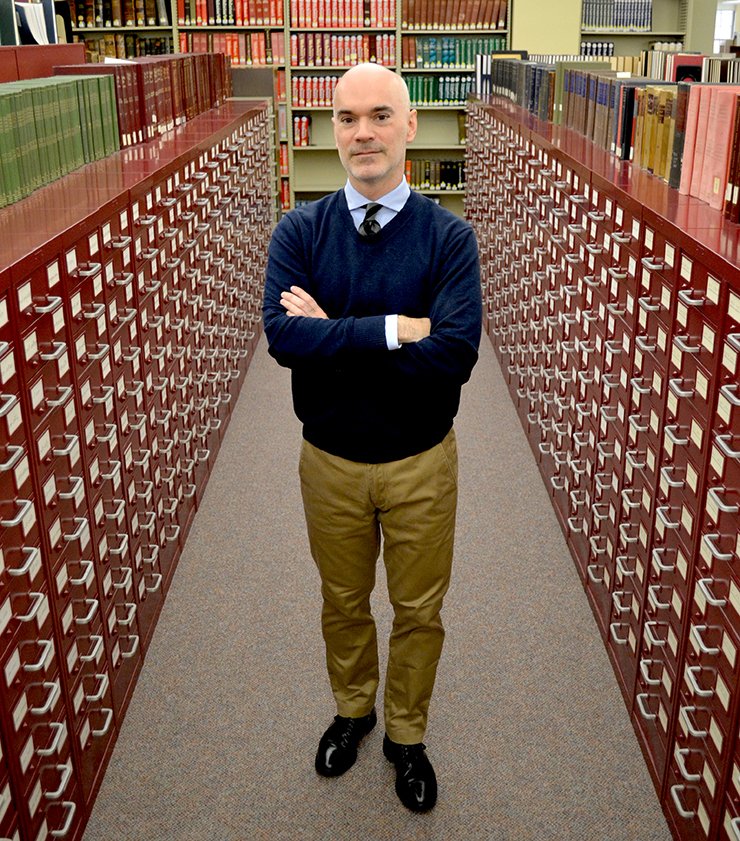

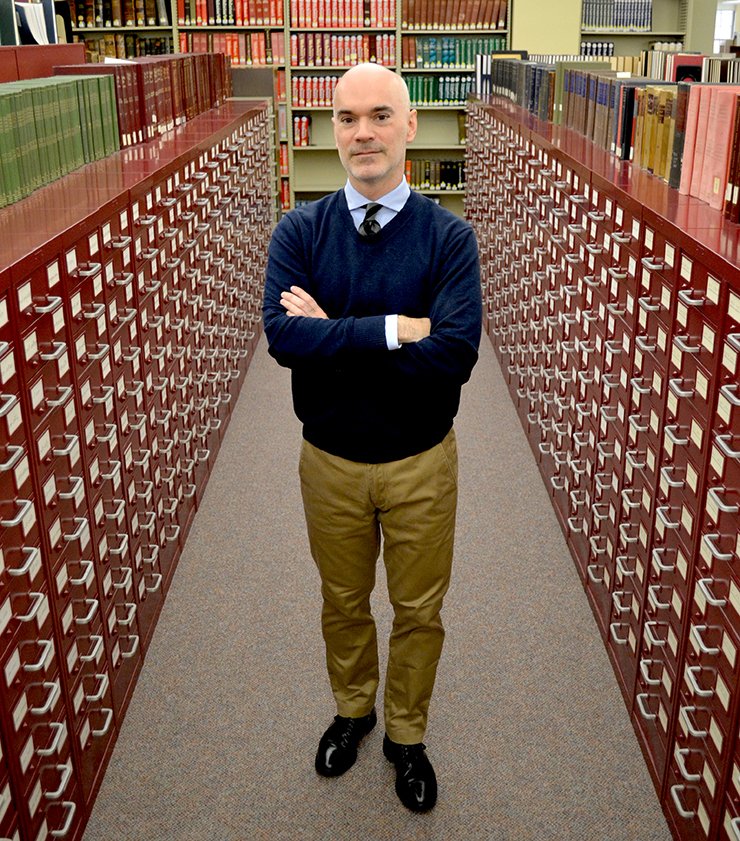

(Kardon: Tony Gale)FRIDAY 1:30 PM

Maysville

17 West 26th Street

Avocado egg salad sandwich: mixed greens, crispy shallots

Cobb salad: romaine, grape tomatoes, avocado, hard-boiled eggs, blue cheese

Cajun spiced nuts: garlic, rosemary

Diet Coke, ginger ale

My first full-time job in New York, after months of freelance proofreading and temp jobs, was at W. H. Freeman, an imprint of Macmillan. On my first day, when I walked through Madison Square Park to the black skyscraper that held my modest cubicle thirty-seven stories above Madison Avenue, across from the iconic Flatiron Building, my heart did a little somersault. I had made it. It didn’t last long—I left that job after eight months or so—but it was still a great moment. I’m in a hurry as I walk through Madison Square Park this afternoon, but every time I’m in the neighborhood I can’t help but look up at that black building to find the window—not mine, I never had one—through which my former boss, Erika Goldman (now the publisher of Bellevue Literary Press), saw the city’s skyline. After a quick look I pick up the pace, fast-walking a couple of blocks west to the restaurant at which I’m meeting Kent Wolf, an agent at the Friedrich Agency. When he suggested Maysville for lunch, I had to look it up to see whether we needed a reservation. It took me thirty seconds to discover that we would be eating lunch two days before the Southern-inspired eatery and bar that boasts 150 different American whiskeys is scheduled to close, for good. Two questions: Does this mean the place will be empty or crowded, and does the drink menu suggest I’ll get a taste of those inebriating publishing lunches I’d read about?

The first question is answered the moment I step inside: It’s neither packed nor deserted, which is not a great sign for a Manhattan restaurant on a Friday afternoon, hence, I assume, the closing. The answer to my second question takes longer, but in the end: No, those days appear to be over. It’s a couple cans of cold soda for me and Kent, who is from Illinois—he attended Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington—and has a delightfully sly sense of humor. At one point in the conversation he directs my attention to a gentleman wearing an impressive mullet (business in the front, party in the back), a hairstyle we both recognize from our days in the Midwest.

Before moving to the Friedrich Agency, Kent was an agent at Lippincott Massie McQuilkin. He got his start in publishing on the editorial side, at the independent press Dalkey Archive, before working as a literary scout at McInerney International, then moving to Harcourt, for which he was the subsidiary rights manager until 2008, when he lost his job as a result of Harcourt’s merger with Houghton Mifflin.

“This is a very relationship-based business,” Kent tells me after we get settled and I ask him if agents are a particularly competitive bunch. “Whether it’s me or somebody at ICM or somebody at, God forbid, the Wylie Agency, we’re all good at our jobs; we all have the same relationships, but sometimes authors look for different kinds of experience, and some prefer being at a boutique agency like the Friedrich Agency because we’re very hands-on, and you don’t have to go through layers of nameless assistants—you know, like binky urban assistant at icm dot com—to get to me, Lucy Carson, Heather Carr, or Molly Friedrich,” he says, referring to the sole members of the Friedrich Agency team. “But some authors prefer someone in accounts payable who processes their checks, or the allure of a foreign-rights team, or an agency that has their own book-to-film division, and those are things we can’t provide as an agency. But if you look at our track record, it speaks for itself.”

This is true, and among the agency’s impressive roster of clients, one in particular jumps off the page: Carmen Maria Machado, who is represented by the guy sitting across from me.

Just as Julia Kardon reached out to Brit Bennett after reading an essay she had published online, Kent got in touch with Carmen in 2015 after reading a piece she’d written for the Rumpus. Throughout our conversation Kent drops a number of references to literary magazines—Ploughshares, Guernica—that he scours, looking for new talent. I ask him if he can list more of his favorite journals. “If I tell you, then other agents will start reading them,” he says, which makes me think my earlier question about competition among agents was on point. Saturdays and Sundays, he says, one can find him in the reading room of the Center for Fiction, just around the corner from where he lives in Brooklyn, reading stories and manuscripts. He found another of his clients, Ingrid Rojas Contreras, after reading a story of hers in Guernica. Her debut novel, Fruit of the Drunken Tree, was published by Doubleday in July 2018.

Doubleday, of course, is a part of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, which is itself a part of Penguin Random House, the multinational conglomerate formed in 2013 from the merger of Random House, owned by German media conglomerate Bertelsmann, and Penguin Group, owned by British publishing company Pearson.

Carmen’s story collection, Her Body and Other Parties, did not find a home at Penguin Random House, or any of the other publishers comprising the Big Five that currently dominate the commercial publishing market. As a matter of fact, close to thirty publishers, including some small indies, declined before Kent found an editor and a press willing to take a risk on the debut story collection. “Graywolf was our last port of call,” Kent says. “It’s difficult to say what would have happened if Graywolf had turned down the book. Maybe another small press out there would have taken it. The independent presses are the ones that can take risks because they don’t have shareholders to answer to.… The big trade publishers are just notoriously risk-averse, and they’re getting increasingly so.”

The initial response from publishers to Carmen’s debut reminds me of what happened with the first book by Nathan Hill that Emily Forland was unable to sell. “It’s cliché now, but you hear it all the time,” Kent says. “It’s this exact sentence: Stories are hard. And they say it in this soft, apologetic way—gentle. ‘Send us the novel when it’s ready.’ I was in a meeting with a scout, and I was talking about Carmen’s collection, pitching it for foreign sales. And the scout, that was the first thing she said: ‘Mmm, stories are hard.’ She was like twenty-two. What do you know? Your boss says that, so now you’re parroting it. I told her she was never allowed to say that to me again,” he says, grinning.

In the end, Ethan Nosowsky at Graywolf Press bought Carmen’s story collection, and it was published in October 2017. The book that was passed on by the New York publishing establishment went on to be named a finalist for the National Book Award, the Kirkus Prize, the Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction, the Dylan Thomas Prize, and the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction. It won the Bard Fiction Prize, the Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Fiction, the Brooklyn Public Library Literature Prize, the Shirley Jackson Award, and the National Book Critics Circle’s John Leonard Award. Last year the New York Times listed Her Body and Other Parties as one of “15 remarkable books by women that are shaping the way we read and write fiction in the 21st century.”

“There was a lot of revisionist history going on in New York” once it was clear what all those editors had passed on, Kent says, then adds: “You can write that my eyes rolled so hard my irises disappeared.”

When I ask him to elaborate, he gives me a kind of side-glance, grins, and says, “This is a risk-averse industry, unless they can see an audience for something. That’s why they’re always insisting on comps.” Comps, by the way, is short for “comparable titles,” which are standard ingredients in any query letter or proposal. Agents and editors want to know the titles of some recently published books that have proved successful (but not too successful) and that share some characteristics with what you’ve written. “A book doesn’t exist in a vacuum,” Kent says, repeating what a couple of the other agents said earlier in the week. “So if [editors] can point to this particular recent success, or something that recently won an award or was turned into a movie or whatnot, if they can see that there is an audience for something, then they can more comfortably get behind that.”

On the other hand, writers often hear publishers and editors talking about how they’re looking for the next new thing: something exciting, something they haven’t read before. There is an inherent contradiction at play here, and it triggers one of Kent’s biggest complaints about the industry. “Here is one thing I hate about this business: publishers massively overpaying for debut fiction. It’s the worst. Two or three million dollars for a debut novel and everything else on that publisher’s list gets eclipsed by that book; they put all of their efforts behind it,” he says. “They circle their wagons around one, two, three books a year, and everything else is getting lost. This is not a sustainable model. It’s bad for publishers, it’s bad for authors, it’s bad for readers.”

Carmen’s second book, a memoir, In the Dream House, will be released by Graywolf in November, and despite the early rejections of her debut, it is difficult to see how her career would have been launched any better at one of the bigger publishers. “With Graywolf, it’s a smaller list, and the attention they pay to each book is noticeable,” Kent says. “What’s nice for an author being published by a press like Graywolf is that they’re more part of the process. And I think authors are given more agency, or at least they are able to be part of decisions in a way that a [larger publisher] couldn’t offer because of the layers of bureaucracy.”

MONDAY 1:00 PM

Taylor Street Baristas

28 East 40th Street, between Madison and Park Avenues

Granny’s chopped salad: romaine, cucumber, avocado, tomato, feta, smoked salmon

Smoked tomato soup and grilled cheese sandwich

Nishi Sencha tea, filter coffee

I was warned that Taylor Street Baristas would be loud, and as I make my way through Grand Central Terminal and walk two blocks south on Park Avenue to the specialty coffee shop and café, I take Emily Forland’s advice to hope for the best and expect the worst. Unfortunately, my fears are realized when I walk in the door. I believe clamorous is the word. So many people talking so close to one another (the Midwesterner in me will never get used to tables positioned this close) that I worry I won’t be able to hear my lunch companion, Marya Spence, an agent at Janklow & Nesbit. As I wait for her at a corner table in the second-floor dining room, music is added to the din. I would be annoyed if not for the playlist (sweet sounds of the 1970s, “Running on Empty” by Jackson Browne, followed by Steely Dan’s “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number,” offer an appropriate soundtrack for this rainy day), and soon enough my ears adjust and Marya arrives.

Having studied literature at Harvard, followed by an MFA in fiction at New York University, during which she had paid internships at the New Yorker and Vanity Fair—she also wrote reviews for Publishers Weekly and taught undergrads—Marya seemingly could have had her choice of careers in the editorial or academic arena. Toward the end of her time at NYU, she began to look into teaching, a profession that was familiar to her. (She grew up on college campuses; her father is a prize-winning professor and administrator who taught at schools across the country). But while Marya was applying for adjunct teaching jobs, the writer David Lipsky (Although of Course You End Up Being Yourself: A Road Trip With David Foster Wallace) suggested she look into agenting. “I really had no idea what agenting was at that time,” she says, but Lipsky knew someone at Janklow & Nesbit, an agent who specialized in young adult fiction and is no longer with the firm, so she sent her résumé, which floated down the hallway to another agent, PJ Mark, who brought her in for an interview. “I came in, wrote an editorial response on a manuscript, and we were off to the races,” Marya says. She started as PJ’s assistant while doing what many assistants do: try to build their own list of clients. “I was working on some projects of my own…doing that thing young people have to do in publishing, which is working double triple time. I was my boss’s assistant during work hours, and then I would stay late editing some manuscripts that I hadn’t formally signed yet. But that’s how you get your foot in the door.”

One of the books that landed on her desk in those early days, in January 2015, to be precise, was Goodbye, Vitamin, a novel by Rachel Khong, then senior editor at Lucky Peach, the irreverent food magazine that would shutter two years later. The novel, about a thirty-year-old woman who returns home to Southern California for Christmas and ends up staying to care for her ailing parents, made an immediate impression.

“I read Goodbye, Vitamin overnight, and I cried on the subway and I cried at my neighborhood bar, where I would sit in the corner and they would pour me tea—it was very romantic, my life then,” Marya recalls. “And I walked into PJ’s office and said, ‘Look, I haven’t asked to sign anyone yet, particularly one that came to both of us, but [she pauses] this is my book. It has to be.’ And PJ was drowning, as I am now, and was like, ‘Please, you have more than my blessing.’”

So Marya sent Rachel an editorial letter—she calls them love letters—in which she put all of her thoughts and visions and desires for the book, comparing her work to Renata Adler (Speedboat) and Jenny Offill (Dept. of Speculation), and explaining some of the editorial work she thought the manuscript needed, including tightening the pacing in some places and building up some of the characters. “I will admit I’m a sucker for romance or a crush story, so I wanted that to be built out a little bit more too,” she says.

Rachel happily agreed, and for the next ten months or so, the agent and author worked together on the manuscript. Meanwhile, Marya made her first sale: Jaroslav Kalfar’s Spaceman of Bohemia to Ben George at Little, Brown, in a six-figure preempt—not a bad way to start an agenting career. When Goodbye, Vitamin was ready for submission, it too received an “overwhelming response,” attracting more than a dozen interested editors. Before the auction, Marya scheduled what she describes as “a week of back-to-back, on-the-dot forty-five-minute phone calls” between Rachel, who lives in San Francisco, and her suitors.

I ask Marya what exactly happens during these kinds of phone calls—or typically, if the author is in New York, in-person meetings—before an auction begins, and whether the conversations are primarily for the editor’s benefit or the author’s. “First and foremost it’s for the writer,” she says. “Editors’ responses to a manuscript can range from ‘I’m interested but with some qualifications,’ in which case a talk is really important for them to just speak directly and get a sense for each other’s styles and personalities, to ‘I’m just freaking out, I’m losing sleep over this book, and I just want to tell this person how much I’m dying to work with them,’ which is also good for a writer to hear.”

In Rachel’s case the responses were similarly varied, so it was important for her to get a sense of where each editor stood before the auction began. As a result of one of the phone calls, an excited editor made a preemptive offer. “With all of the interest, we didn’t take it,” Marya says. “It was a really nice preempt from an amazing editor and house, but I wanted Rachel to know where some of these other houses and editors were coming from.” Instead Sarah Bowlin, a senior editor at Henry Holt, won the auction and the rights to publish Goodbye, Vitamin.

Fantastic news, but then what? I’ve always been curious about the moments, days, and weeks following such a momentous decision. Here’s a debut novelist whose life has just been changed by a series of e-mails and phone calls on the other side of the country. What’s the next step?

“The next step is getting on an e-mail chain together, and there’s lots of exclamation points,” Marya says. “I think it’s really important to celebrate. This is a moment where everything has gone right. Cherish that.” This is solid advice. But an agent doesn’t just raise a glass, then hand over the keys and wish the writer well. There are a number of things that require her attention: The finer points of the contract need to be settled—the formats and markets in which the book will be published, subsidiary rights, payment schedule, due dates, options, and so on—and the publisher’s contracts department likely needs a little nudging. And then there’s getting everyone together—the author, the editor, the publicity and marketing team—so they can draw up a game plan for publication.

Still, on some level there is a handoff that happens naturally after the author and editor have been introduced. “I like to be looped in on everything, but I also want writers to have direct relationships with their editors,” Marya says. “As much as I would love to be a part of every step of the editorial process, I just can’t be, so they need to get comfortable as soon as possible. I think of it sometimes like a relay race. Up until that point, for months or maybe years I’ve been working with my writer on a super-familiar basis; now the ball is more in the editor’s court, and they might step into that role of editorial and creative collaboration.”

But then sometimes, as was the case with Rachel, the unexpected happens: Sarah Bowlin left Holt. As a matter of fact, she left editing altogether: She moved to Los Angeles and is now an agent at Aevitas Creative Management. “So then the book was reassigned to Barbara Jones, who is wonderful,” Marya says. “I could think of no better editor to take up the mantle than her. She had said that she was the first person to raise her hand to take it on because she read it and cried during submission.”

Marya calls the departure of an editor mid-process “very disruptive,” but in this case it didn’t spell disaster. The publisher was already fully behind the book, and it had already been edited, but there were still many things to be done before publication, including finalizing the cover. Marya stayed on top of the situation. “I think authors need to hear, ‘Don’t worry, I’m on top of them. I’ll make sure that these balls don’t get dropped.’”

Agents, of course, are good at juggling, and after Goodbye, Vitamin was published in July 2017, it was named a best book of the year by nearly a dozen major publications, including O, the Oprah Magazine; Vogue; Esquire; Entertainment Weekly; and BuzzFeed. It went on to win a 2017 California Book Award and was a finalist for the Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction.

I ask Marya if she has any advice for authors in the middle of the publishing process, who may be juggling a bit of anxiety themselves. “Recognize that there will always be surprises along the way,” she says, “and know that we’re on your team.”

Talk to an agent long enough, over a good meal, and inevitably subjects will come up that are, shall we say, sensitive. As many of these agents reminded me, this is a business of relationships—one even said it’s a business of feelings—so there are stories, or bits and pieces of hard-earned wisdom, that they may not be comfortable having attributed to them. Rather than restrict our conversations, I offered to save such morsels for “dessert,” served cold, names removed. Here then is a collection of unattributed quotes gleaned from our conversations. Some verbal tics and tones have been edited to preserve anonymity and to avoid giving any agent indigestion.

I never predict what someone’s advance is going to be. I tell people that I work on commission, and therefore I don’t take on projects that I think are not going to sell well. But I will never say, “Oh I think this should be around $150,000.” I would just never guess that, because it’s a losing game. You either give them this false hope that you can’t deliver on or you look like you undervalued them, which is also not a good look.

I’ve never been on the phone and said to a client, “No way in hell are you taking this.” We talk it through. I try to give them as much agency in the process as I can, and complete transparency. I’ve never not conveyed an offer to an author. But there are some agents who will keep information from their clients.

The kind of agent who makes a decision that they’re going to represent the most moneymaking clients regardless of what their ideology is—I’m not there. Maybe I will lose money in the long run because of it, but I don’t think that I could be a passionate advocate for a writer whose political opinions I abhor or felt were actively damaging the fabric of society. I mean, it’s not like Steve Bannon approached me and asked me to represent him, but I can at least say that I’m not interested in those kinds of books.

If I share a rejection note from an editor with you, and then you write the editor directly about it, that’s not a good idea. I don’t work with that author anymore.

The numbers are always so made up. The profit-and-loss statements that editors use for debuts are truly nonsense numbers; they’re actually insane.

I like to say I work in the margins of a very commercial space so I take on those things that I feel need to be seen but that I also think I can get into a big trade place and make an advance, which is hard—I’m an agent and I get to choose what I give my time to, but unfortunately it’s also about the money on some level because I have to also make a living. And some of these decisions are also economic.

If your agent gives you honest feedback on the first draft of your novel, that should be considered private correspondence. It is bad form—as well as being really unconstructive—to post it on social media or vent about it on your blog.

There’s a funny story about FSG. I don’t know if it’s apocryphal, but the story goes that an agent and author asked for a marketing plan for a book, and it was just a photo of the spine with the colophon.

Make sure you’re writing for the right reasons. If you’re writing a novel because you’re trying to work through your own personal issues, that’s not why you should be writing a novel.

I’ve definitely talked to people where we disagree about a book, and I very, very rarely say, “I can see your side of things here.” No, my side is right. I knew that book was going to be a big deal, and if it hadn’t been I would have left the industry, because I would not have been able to work with people too stupid to understand what they had in front of them.

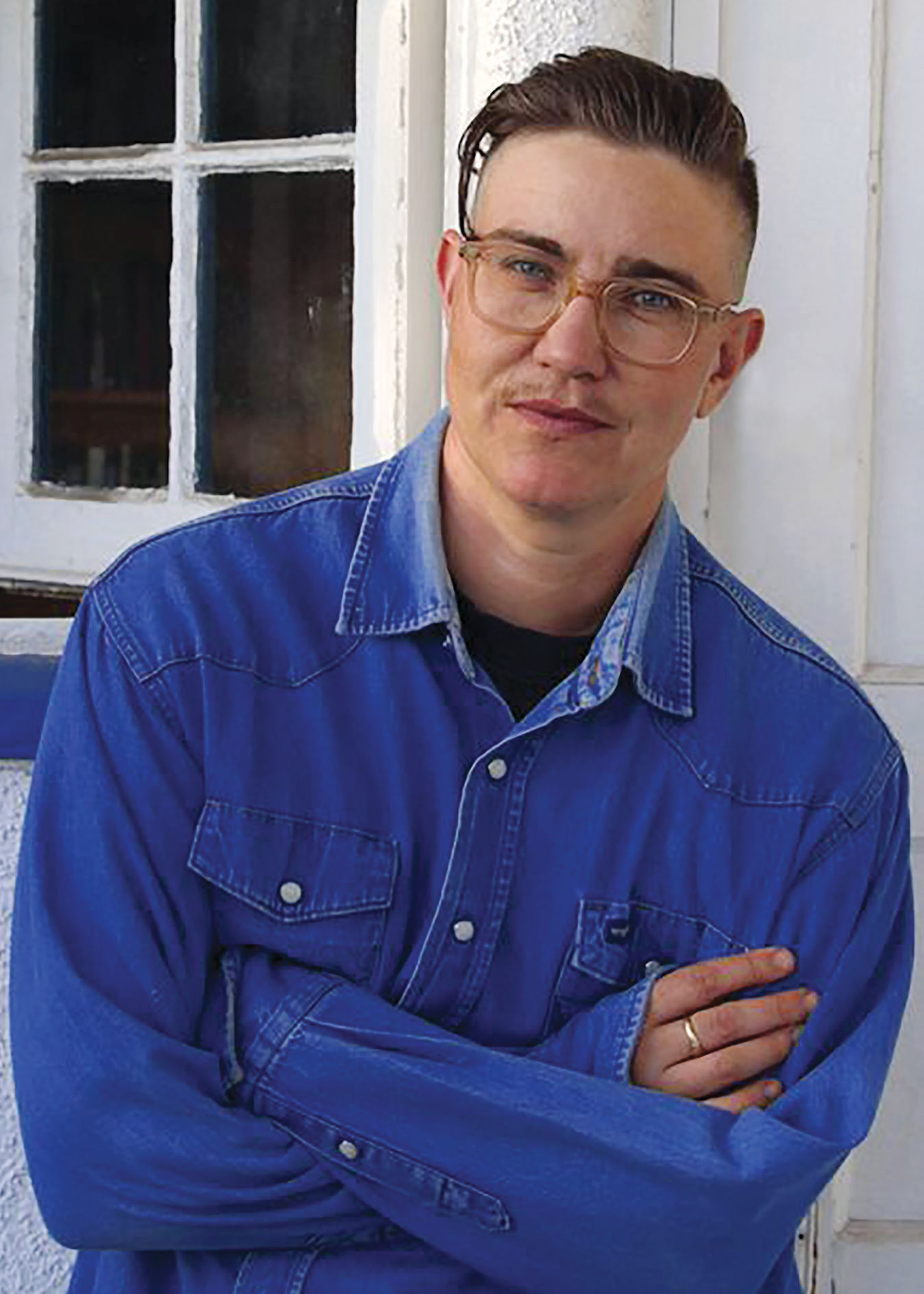

Kevin Larimer is the editor in chief of Poets & Writers, Inc. Follow him on Twitter, @KevinLarimer.

The Business of Relationships: How Authors, Agents, Editors, Booksellers, and Publicists Work Together to Reach Readers

It is often said that book publishing is a business of relationships. Behind every successful title there is a small crowd of people who, over the course of many months and even years, worked together—via e-mail and in person, on the phone and over lunch—to turn an idea into a vision, edits into finished pages, a manuscript into a book. A work of art conceived and created in solitude is carried forth by a team, passing through many hands before it reaches the marketplace. I asked five debut authors to describe their first steps toward establishing the initial relationship, the one that starts the whole process rolling: finding an agent. I then asked those five agents to explain how the relationships with their clients grew and how they introduced their clients to the ideal editors who would shepherd their books into print. Next, I contacted those editors and invited them to walk us through the acquisition and editorial process that turns the raw material into finished products. And finally I spoke with five indie booksellers who convey the enthusiasm, the passion, and the purpose of author, agent, and editor in their efforts to place the books in the hands of their intended readers. Along the way I was introduced to marketing directors, publicity managers, events directors, sales reps, and other agents, editors, and authors who aided in forging connections that proved crucial in the process. The result is a series of illustrations offering a glimpse at how the book business operates on the strength of personal and professional bonds among dedicated people working toward the twin goals of creative expression and smart business.

Jordy Rosenberg author of the novel Confessions of the Fox, published in June by One World, an imprint of Random House

According to my e-mail records, it was seventeen days from when I first e-mailed Susan Golomb to our initial phone call. However, this does not take into account the seventeen years that I spent writing and throwing away manuscripts. During that time I had been fortunate to discuss my different projects with several agents with varying specializations: noir/mystery, creative nonfiction, popular fiction. These conversations ultimately became a part of Confessions, which interweaves all these genres—speculative fiction, thriller, metafiction, autotheory—into a single novel. With such a formal composite, I needed and wanted to work with an agent who specialized in high-concept literary fiction. I knew Susan had worked on this kind of thing with a number of her other clients, so I had hoped Confessions would attract her attention, and to my great fortune it did. But I could not have predicted the storm of activity that would ensue once she took me on. Susan was tireless with her edits. It was a little sublime and terrifying, actually, and I don’t know how she did it. We went through three full rounds of line edits—as well as larger structural edits—in the space of three weeks. This mania was surely responsible for the fact that Susan was struck with pneumonia midway through the process. Which still didn’t stop her: She was calling me from the hospital about edits. I believe she was still on antibiotics, in fact, when she made the connection between me and Chris Jackson and Victory Matsui at One World. I’m very much in her debt for the clarity of her vision, not only about the book’s bones, but also for intuiting that the horizon of the book’s potential lay with Chris and Victory and the deep working relationship we would go on to establish.

Susan Golomb of Writers House

When Michael Szczerban interviewed me in your pages in 2014, I made reference to my “shaggy dogs.” Jordy’s novel was one such animal. It came bounding into my slush pile with a mention of my client Rachel Kushner as a referral, wagging its tail with charming yet acerbic wit and playful language that included the actual lexicon of the demimonde, which put me in mind immediately of A Clockwork Orange, but with a bursting heart. There were probably fifty words for sexual intercourse, each more delicious and descriptive than the next, and a thriller frame with extremely topical, political subtext dripping with atmosphere. Like all shaggy dogs, however, its ambition exceeded its reach, so we set to work, and in a hurry, to have it on submission for the Frankfurt Book Fair. I worked with Jordy to trim the plot and imbue it with more suspense, to deepen the characters and raise the stakes of their desires. And I felt the title, while quite apt and intriguing, could be off-putting. So we came up with an interim one—and the final was by way of brainstorming with Writers House colleagues at a party and back and forth with Jordy and the One World team. While racing to meet the Frankfurt deadline, I came down with pneumonia, and Jordy plied me with bone broth, which came by messenger from Brodo and endeared him to me even more than his spectacular talent and, yes, I’ll say it, dogged willingness to make the manuscript as brilliant as it could be.

Victory Matsui editor at One World

When Susan Golomb sent the novel to me and Chris Jackson on submission, I had just joined One World a month earlier. I was searching for fiction that fulfilled the One World mission—books that “challenged the status quo and subverted dominant modes of thinking.” I was especially looking for a novel that celebrated the political resistance and joyful weirdness of queer and trans communities. Can you imagine how I felt when I first read Confessions? Jordy had merged a radical sensibility with the pleasures of great storytelling to write an epic queer love story through the histories of capitalism, imperialism, and imprisonment. Chris and I quickly set up a call with Susan and Jordy, and we immediately fell in love with his electric mind, his sense of humor, and his ambition to make this book both intellectually engaging and richly entertaining. We set down the phone and agreed we had to publish this book. So we offered a preempt—an offer that takes the book off the table before other editors have the chance to offer—and were overjoyed when Jordy and Susan accepted. Of course that was just the beginning: Our work together would take us from nights of e-mailing back and forth about character backstory to long phone calls about narrative structure to a tearful meeting at Le Pain Quotidien about footnotes—ultimately resulting in one of the most fulfilling editor-author relationships of my life.

Alex Schaffner at Brookline Booksmith in Brookline, Massachusetts

First an advance reader’s copy (ARC) arrived addressed to our backlist buyer, Shuchi Saraswat, who keeps an eye out for booksellers’ interests as ARCs come in. She and my co–events director, Lydia McOscar, heard more about the book directly when they visited Penguin Random House’s New York offices. The publisher’s contagious enthusiasm spurred me to dig in. LGBT literature is one of my key interests, and I wrote a thesis on eighteenth-century literature, so this was a natural path from publisher excitement to store to just the right bookseller. Fans of Sarah Waters and Jeanette Winterson will love it, and with hand-selling and shelf-talkers [printed cards or other signs attached to a store shelf to call buyers’ attention to a particular title], I expect the book to be a success at the store.

“Rosenberg’s masterful debut is, at once, a work of speculative historical fiction, a soaring love story, a puzzling mystery, an electrifying tale of adventure and suspense, and an unabashed celebration of sex and sexuality.”

—Christine Mykityshyn, publicity manager, Penguin Random House

Nafissa Thompson-Spires author of the story collection Heads of the Colored People, published in April by 37 INK, an imprint of Atria Publishing Group

In 2015 I started querying agents with a novel I’d written as my MFA thesis at the University of Illinois. No one was sure about its genre—YA or adult literary fiction. After a lot of partial requests and a dozen full requests, lots of rejections, and lots of agents ignoring me—I queried about a hundred—an agent asked me to revise and resubmit. I grew bored with trying to write to his suggestions; to distract myself I wrote several short stories. One of them, “Heads of the Colored People,” gave me the idea for a full manuscript. In early 2016 I ran into an old colleague, Jensen Beach, who recommended that I submit my completed collection to some contests and mentioned that he could refer me to his agent, Anna Stein. Two weeks later the collection won a small-press contest that came with publication, but I wasn’t sure if that was the best route. I contacted Anna and the three or four other agents I’d submitted to, strategically this time. Anna responded enthusiastically that I should talk to her instead of giving the book to the small press. We clicked on the phone, and the rest is a blessed history.

Anna Stein of ICM Partners

Nafissa’s collection came to me thanks to my client Jensen Beach, who had recommended us to each other. I remember my assistant at the time, Mary Marge Locker, started reading before I did and said, “You’d better take this home with you.” At the time I was living in a one-bedroom apartment with my husband and two young daughters, so I headed off to a café to read. I was immediately immersed and engaged. The collection was just so surprising, so refreshingly unexpected. There was a kind of cool intellectual perspective that made the stories feel like they were operating at different registers simultaneously. I didn’t have to think twice; we started working together the very next week.

Dawn Davis vice president and publisher of 37 INK

The submission came in via Anna Stein of ICM, a literary agent who has represented two of my favorite contemporary novels, A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara and Where’d You Go, Bernadette? by Maria Semple. I jumped right in and was struck by how fresh the stories were but also by Nafissa’s mordant use of humor to talk about race and isolation. It was dark at times, which I was used to; novels about black life are often dark. But the irony and wry wit was strikingly original—and at times bold. I ate it up. When Nafissa and I spoke on the phone, I expressed my enthusiasm for what I loved about Heads of the Colored People—the title story and “Wash Clean the Bones” broke my heart, while “Belles Lettres” had me laughing with glee—and I was candid about what I thought was missing. She was respectful, curious, and open.

Rick Simonson at Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle

Dawn Davis and I have kept in touch for more than twenty years—for however long wherever she’s worked—including wide-ranging talks on books and publishing, above and beyond any particular title. But there have been particular books over which we make a special connection. Maybe most memorable was The Known World by Edward P. Jones. She sent early manuscripts of that book out to a few of us, and so, too, with Heads of the Colored People, which she told me about some time ago. Then I’ll get a galley with a note: “Finally, this.” It is, without fail, extraordinary when she makes these connections. She has that eye. Also playing a part, in her own way, is our Simon & Schuster sales rep, Christine Foye, who is attuned to editors’ books, Dawn’s among them. Heads of the Colored People is very much of the present time, and it is finding readers here at Elliott Bay from the get-go.

“Her stories are exquisitely rendered, satirical, and captivating in turn, engaging in the ongoing conversations about race and identity politics, as well as the vulnerability of the black body.”

—Stephanie Mendoza, senior publicist, Simon & Schuster

Rachel Z. Arndt author of the essay collection Beyond Measure, published in April by Sarabande Books

I was lucky to have met some great agents when I was in grad school at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and the University of Iowa’s nonfiction writing program. The most substantive conversations with these agents took place during my third year, when I had an idea of the book I wanted to make. I honed my pitch as I met with more and more people and as I learned to describe my essay collection in terms of what I was working toward, not necessarily what I had then. One of those people was Samantha Shea. I gave her some essays when I was still in school, and after I graduated, I sent her my thesis—which would eventually become a good chunk of my book. The summer after graduating, Samantha took me on, immediately offering invaluable guidance and feedback.

Samantha Shea of Georges Borchardt, Inc.

Rachel and I first met when I visited the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in early 2016. She reached out a few months later to say that she had a complete essay collection and an offer from Sarabande. I quickly read the work she sent me and was so impressed with the thoughtfulness of her writing—its searching quality, its currents of existential frustration, fear, and longing. We began working together right away—first negotiating the deal with Sarabande and, later, placing other work of hers, including some of the essays in the collection, with journals and magazines like Woolly, the Believer, Literary Hub, and Longreads.

Sarah Gorham president and editor in chief of Sarabande Books