“To deprivatize is not the same as to make public. A field is only natural or private after so much hurt.” In this short film, Jos Charles offers a preface for her poetry collection feeld (Milkweed Editions, 2018), which was a finalist for the 2019 Pulitzer Prize in poetry.

Jos Charles: A Preface

Summer Reading Recommendations

In this PBS NewsHour video, NPR’s Maureen Corrigan and the Washington Post’s Carlos Lozada highlight their favorite books for summer reading, which include Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (Penguin Press, 2019), Jill Ciment’s The Body in Question (Pantheon, 2019), and José Olivarez’s Citizen Illegal (Haymarket Books, 2018).

Chad Sweeney

“Seeing is an act of imagination. When I am stuck in writing, it means that I have stopped seeing, that I have reduced the myriad forms to irrelevant background shapes like extras in a film, that I have closed off the sense doors to dwell in an anxious hermitage of bills and paperwork. Taking a walk is helpful, but no matter where I am, I can shift over to this alert mode of experience and feel changed by it: exhilarated by gradations of the violet whirl of bushes, the intricate mazes of wood grain in the table, the slapping of a child’s sandals, the whirring shadows of the ceiling fan against kitchen tile. Rather than feel pressure to complete a poem, I merely write perceptions, compositions in motion, textures, contrasts, distances, sounds, frames, traceries and scatterings, as if the world were a cubist painting or sculpture garden. From these prima causa observations—and in a state of gratitude and excited receptivity—the words begin to rise or fracture into liminal spaces quivering with mystery and potential. These are the poems that tell the most surprising truths, of me and beyond me, in collaboration with these parrots turning above the orange grove and a coal barge on the Mississippi of my own distant childhood.”

—Chad Sweeney, author of Little Million Doors (Nightboat Books, 2019)

Roughhouse Friday

“Every conversation between us then had a way of spiraling into the same abyss. Real men were impossible to understand. Real men suffered. Real men were broken.” Jaed Coffin reads from his second memoir, Roughhouse Friday (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019), which is featured in Page One in the July/August issue of Poets & Writers Magazine, and talks about his experiences barroom boxing in Alaska with Kathryn Miles for Portland Public Library’s Literary Lunch series.

To Make Use of Water

“Back home we are plagued by a politeness / so dense even the doctors cannot call things / what they are…” Safia Elhillo narrates her poem “To Make Use of Water” from her collection, The January Children (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), for this animated TED-Ed film directed by Jérémie Balais and Jeffig Le Bars.

Alfredo Aguilar

“From the window I watched older men push carts between stopped cars...” In this video Alfredo Aguilar, one of the winners of 92Y’s 2019 Discovery Poetry Contest, reads his poem “My Mother Drove Us Into Tijuana for Dentistry.”

Jill Ciment

“I begin my writing day with a sip of coffee and a vape (or two) of marijuana. (Disclaimer: I live in a state where medical marijuana is legal.) I never actually compose stoned, but I do read what I wrote the day before and take notes—silly, hallucinatory notes, but sometimes ideas that I might not have stumbled upon otherwise. The high, which also causes me to be forgetful, makes rereading a paragraph that I have read a hundred times before feel fresh and full of possibilities. The intoxication never lasts more than fifteen to twenty minutes and then I get on with the business of writing. But the high reminds me (and I need to be reminded every day) that writing can be joyous. Take time to be playful with your writing, with whatever practice works for you.”

—Jill Ciment, author of The Body in Question (Pantheon, 2019)

Ten Questions for Helen Phillips

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Helen Phillips, whose novel The Need is out today from Simon & Schuster. The Need is an existential thriller about Molly, a scientist and mother of two young children. When a masked intruder appears in her home and demonstrates an eerie familiarity with the inner workings of her life, Molly falls down a mind-bending rabbit hole. A paleobotanist who has recently uncovered an array of peculiar artifacts at her fossil quarry, Molly eventually learns the true identity of the intruder, forcing her to confront an almost impossible moral decision with far-reaching repercussions for her children. Helen Phillips is the author of the story collections Some Possible Solutions (Henry Holt, 2016), which received the 2017 John Gardner Fiction Book Award, and And Yet They Were Happy (Leapfrog Press, 2011); the novel The Beautiful Bureaucrat (Henry Holt, 2015), a finalist for the New York Public Library’s Young Lions Award and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize; and the children’s adventure book Here Where the Sunbeams Are Green (Delacorte Press, 2012). A graduate of Yale and the Brooklyn College MFA program, she is an associate professor at Brooklyn College. Born and raised in Colorado, she lives in Brooklyn with her husband, artist Adam Douglas Thompson, and their children.

1. How long did it take you to write The Need?

I began the long, chaotic document of notes that would grow into The Need in February of 2015, and I handed the final draft in to my editor in September of 2018. But the urgency to write a book about motherhood arose in me in the summer of 2012, when my daughter was born and my sister died, though it took me some years to approach the material.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The most challenging thing about writing the book was the emotional task of trying to evoke grief on the page. I shied away from that pain in the first draft. When I went back in to revise, it required me to go on an emotional journey. I have never before written something where the primary challenge was not one of craft or character or structure but rather of emotion.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

During the semester, when I’m teaching at Brooklyn College, I typically write one hour a day, five days a week, sometimes in my shared office on campus and sometimes at home. I put on a timer and protect that hour. The moment the timer rings, I’m off to teach or to prepare for class.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

Simon & Schuster sent me on a pre-publication tour to meet with independent booksellers at Winter Institute in Albuquerque, and in Seattle, the Bay Area, Boston, and New York. It was fascinating to meet indie booksellers from across the country. For one thing, indie booksellers are (unsurprisingly) a very smart, funny, and thoughtful group. And I was surprised and excited by the positivity they seem to feel about the industry overall—they are selling a good number of books, hosting a lot of events, playing a central role in their communities.

5. What are you reading right now?

I recently finished Mira Jacob’s Good Talk and Ben Lerner’s The Topeka School, both of which I loved. I’m currently reading Darcey Steinke’s riveting Flash Count Diary. Next up is Rumaan Alam’s That Kind of Mother. And my book tour reads will include Valeria Luiselli’s Lost Children Archive, Esmé Weijun Wang’s The Collected Schizophrenias, and Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

The Swedish writer Karin Tidbeck, whose novel Amatka is an exquisitely written evocation of a dystopian society where everything that isn’t properly labeled with a name-tag turns to sludge. One of my favorite books in recent years.

7. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started writing The Need, what would say?

Don’t be scared of the tension and grief that has to be present in this book.

8. What has changed about your writing process over the years, since writing your first book?

When I wrote my first published book, And Yet They Were Happy, as well as three other long-since-thrown-away novels before it, I had a lot more time to write. I had an administrative job and was teaching night classes, but still I could fit in three to four hours of writing time before going to work. When I became a mother, my daily writing time shifted from four hours per day to one hour per day. But it’s a quality-over-quantity thing, or so I tell myself; now I shove the energy of four hours into my single hour.

9. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

The biggest impediment to my writing life is also the biggest inspiration for my writing life: my children.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I always go to Samuel Beckett’s “Fail again. Fail better.” And, Toni Morrison’s “A failure is just information.” Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about Isak Dinesen’s “I write a little every day, without hope, without despair.”

Ten Questions for Caite Dolan-Leach

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Caite Dolan-Leach, whose novel We Went to the Woods is out today from Random House. Certain that society is on the verge of economic and environmental collapse, five millennials flee to Upstate New York to transform an abandoned farm, once the site of a turn-of-the-century socialist commune, into a utopian compound called Homestead. What starts out as an idyllic sanctuary, however, soon turns dark, deeply isolating, and deadly. Caite Dolan-Leach is a writer and literary translator. She was born in the Finger Lakes region of New York and is a graduate of Trinity College Dublin and the American University in Paris. Her first novel, Dead Letters, was published by Random House in 2017.

1. How long did it take you to write We Went to the Woods?

I worked on it for about two and a half years.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I started the book before the 2016 elections, and my feelings about the characters and their sense of political doom really changed—I had to take a moment to reconsider what they were trying to do and their motivations for doing it. It definitely slowed me down.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I travel a bit, so the “where” tends to be a variable: sometimes my desk at home, sometimes a café in a different country, sometimes a hotel room. But I work best in the mid-morning, and I try to write at least four days a week.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

This is my second book with Random House, so there weren’t too many surprises. But I’m always struck—and deeply grateful—at how many people are involved in a book’s life, and how much time and effort goes into the publication process. As a young reader, I don’t think I imagined the dozens of people who contribute to just one manuscript, and as a writer, it’s simply amazing.

5. What are you reading right now?

I just got back from Italy, so I’ve been reading some Italian novels: Sabbia nera by Christina Scalia, and L’amica geniale by Elena Ferrante—I read the English translation a few years ago, but I’ve missed working in Italian, so I’m re-immersing.

6. Who do you trust to be the first reader of your work?

My husband is always the first person who sets eyes on anything I write.

7. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started writing We Went to the Woods, what would say?

Don’t do an outline! I did a pretty detailed outline for this book, and I think it changed how I approached the process, and ultimately made it harder.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Myself.

9. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

I think it’s pretty obvious that we need to be more inclusive as a community. But since I also work as a translator, I’d specifically like to see more books coming from other languages—particularly under-represented ones.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I can’t remember who said it to me, but it’s a truism that I deploy often: Don’t be precious about your writing. By which I mean: Let people read your work, and listen to what they say about it. Obviously, you shouldn’t share until you’re ready, but I think fearing criticism or worrying that people might dislike your work gets in the way of what you really want to write.

Caite Dolin-Leach, author of We Went to the Woods. (Credit: Dominique Cabrelli)

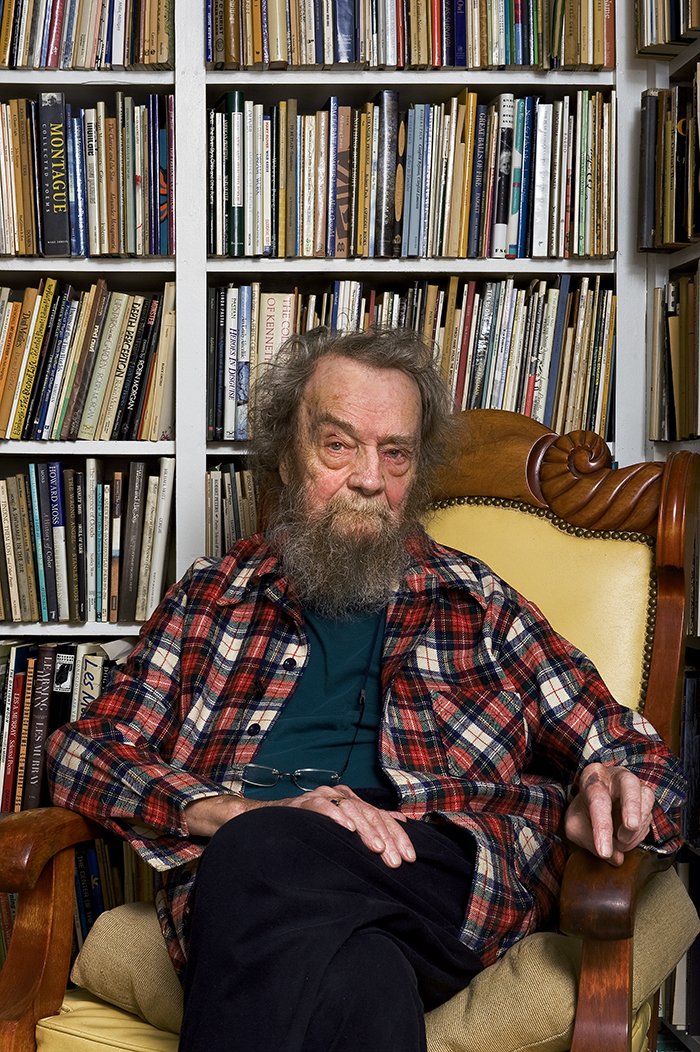

Ten Questions for Peter Orner

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Peter Orner, whose story collection Maggie & Other Stories is out today from Little, Brown. Forty-four interlocking stories—some as short as a few paragraphs, none longer than twenty pages—are paired with a novella, “Walt Kaplan Is Broke,” that together form a composite portrait of life so intricately drawn, line by line, strand by strand, that it shimmers with the heaviness and lightness of the human experience. As Yiyun Li wrote in her prepublication praise, “This book, exquisitely written, is as necessary and expansive as life.” Peter Orner is the author of two novels, The Second Coming of Mavala Shikongo and Love and Shame and Love, and two story collections, Esther Stories and Last Car Over the Sagamore Bridge. His latest book, Am I Alone Here?, a memoir, was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. Orner’s fiction and nonfiction has appeared in the New York Times, the Atlantic Monthly, Granta, the Paris Review, McSweeney’s, the Southern Review, and many other publications.

1. How long did it take you to write Maggie Brown & Others?

Hard to say. Stories come slow and I try not to force them. One, “An Ineffectual Tribute to Len” I began in 1999. Many of the others I carried around for years before I managed to put them right, or sort of right. The novella took about ten years.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

For me the stories in a collection should be both disparate and—somehow—cohesive. Cohesive isn’t the right word. They should talk to each other, I guess is what I’m trying to say. And I like for stories to talk to each other across generations, across geography. So they can’t all be speaking in the same voice, and yet, like I say, they’re communicating, or at least trying to. This takes years and a lot of fiddling, in the sense of fiddling as tinkering—and fiddling as in fiddling around, riffing, etc. (I flunked violin, but I still have aspirations.)

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Whenever I’m not reading, and I read all the time. I squeeze some of my own stuff inbetween. Mornings are the best when my head is a little less cluttered.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

Though this is my sixth book, I take nothing for granted. When the book comes in the mail I’m still astonished by the physicality of it. For days I walk around with it, sleep with it. It’s weird. I wish I wasn’t serious.

5. What are you reading right now?

The poetry of Ada Limón.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Randal Kenan, author of Let the Dead Bury Their Dead, a seminal story collection published in the early ’90s.

7. Do you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

It’s like asking, “So, should I marry this guy?” Well, I dunno. Is he kind? How about the snoring? If the question is, does a writer need an MFA? No. Can it help to be surrounded by other neurotics who love literature? Sometimes. Sure. Doesn’t make it any less lonely though, which as it should be.

8. What has changed about your writing process over the years, since writing your first book?

If anything, I feel less confident than ever I’m going to be able to make a story work. Back around the time of Esther Stories I remember days when I felt I could make a story out of anything. I was kidding myself, but sometimes kidding yourself tricks you into working harder.

9. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Myself, myself, myself.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

My old teacher and friend Andre Dubus would often say: “You got to walk around with it. Walk around with it. You’ll get it.” He meant, in a sense, that sometimes you got to get up and leave the story, walk around, live a little—and when you least expect it, there’s your ending.

Peter Orner, author of Maggie Brown & Other Stories. (Credit: Pawel Kruk)

Ten Questions for Chanelle Benz

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Chanelle Benz, whose novel The Gone Dead is out today from Ecco. As the novel opens, Billie James returns to the shack she inherited from her father, a renowned Black poet who died unexpectedly when Billie was four years old, in the Mississippi Delta. As she encounters the locals, including the McGees, a family whose history is entangled with hers, she finds out that she herself went missing the day her father died. The mystery intensifies as “the narrator and narrative tug at Mississippi’s past and future with equal force,” Kiese Laymon writes. Chanelle Benz has published short stories in Guernica, Granta, Electric Literature, the American Reader, Fence, and the Cupboard. She is the recipient of an O. Henry Prize. Her story collection The Man Who Shot Out My Eye Is Dead was published in 2017 by Ecco Press and was named a Best Book of 2017 by the San Francisco Chronicle. It was also longlisted for the 2018 PEN/Robert Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction and the 2017 Story Prize. It won the 2018 Sergio Troncoso Award for Best First Fiction and the Philosophical Society of Texas 2018 Book Award for fiction. She lives in Memphis, where she teaches at Rhodes College.

1. How long did it take you to write The Gone Dead?

About five years, though some of that time I was also working on finishing my story collection.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Getting the voice of the main protagonist right. I tried different points of view, dialing it up and down, but it wasn’t until I shifted my attention to developing the voices of the characters around her that she finally came into relief.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write in bed, at the dining room table, and occasionally in my actual office. When I’m on a deadline, I try to dedicate some hours late morning/early afternoon, or every other day if I’m teaching. I also write at night if need be—I have a small child so I can’t afford to be particular. But I’ve always tried to be flexible because I came up in the theatre which demands you come onstage whenever and however you may be feeling.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

That some readers see the book as a thriller or mystery, which I’m totally comfortable with, but it was unexpected. I felt that I was structuring the novel the only way it could work. But then so many of the stories I am drawn to are mysteries, whether existential, psychological, or the more classic murder mystery.

5. What are you reading right now?

Casey Cep’s The Furious Hours and Daisy Johnston’s Everything Under.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Jennifer Clement’s work is so fantastic, so luminous, so cutting that I don’t understand why she’s not wildly famous.

7. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started writing The Gone Dead, what would say?

Don’t be careful; definitely not in the first draft. I was so worried when I began the book about doing the time and its people justice that for quite a while I didn’t let my imagination take the lead, which can happen when grappling with the dark side of history.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Student loan debt.

9. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

Yes, as long as it doesn’t put them in debt. I found that the time and space to write was an incredible, powerful gift.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

That’s impossible for me to narrow down! But I often think of something the theatre director and theorist Jerzy Grotowski said: “Whenever the ground shakes beneath your feet, go back to your roots.” (I may be paraphrasing there.) I interpret this as whenever you fail or meet with rejection or some experience that saps your heart, that you remember why you started writing, what you fell in love with reading, whatever it was that first inspired you.

Chanelle Benz, author of the novel The Gone Dead. (Credit: Kim Newmoney)

Ten Questions for Catherine Chung

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Catherine Chung, whose second novel, The Tenth Muse, is out today from Ecco. Growing up with a Chinese mother (who eventually abandons the family) and an American father who served in World War II (but refuses to discuss the past), the novel’s protagonist, Katherine, finds comfort and beauty in the way mathematics brings meaning and order to chaos. As an adult she embarks on a quest to solve the Riemann hypothesis, the greatest unsolved mathematical problem of her time, and turns to a theorem that may hold the answer to an even greater question: Who is she? Catherine Chung is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship and a Director’s Visitorship at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Her first novel, Forgotten Country, was a Booklist, Bookpage, and SanFranciscoChronicle Best Book of 2012. She has published work in the New York Times, the Rumpus, and Granta, and is a fiction editor at Guernica. She lives in New York City.

1. How long did it take you to write The Tenth Muse?

From when I first had the idea to when I turned in the first draft, it took about five years, with many starts and stops in between.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

My mind! My mind is the biggest challenge in everything I do. I write to try to set myself free, and then find myself snagged on my own limitations. It’s maddening and absurd and so, so humbling. With this book, it was a tie between trying to learn the math I was writing about—which I should have seen coming—and having to confront certain habits of mind I didn’t even know I had. I found myself constantly reining my narrator in, even though I meant for her to be fierce and brilliant and strong. She’s a braver person than me, and I had to really fight my impulse to hold her back, to let her barrel ahead with her own convictions and decisions, despite my own hesitations and fears.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write where I can, when I can. I’ve written in bathtubs of hotel rooms so as not to wake my companions, I’ve written on napkins in restaurants, I’ve written on my phone on the train, sitting under a tree or on a rock, and on my own arm in a pinch. I’ve walked down streets repeating lines to myself when I’ve been caught without a pen or my phone. I’ve also written on my laptop or in a notebook at cafes and in libraries or in bed or at my dining table. As to how often I write, it depends on childcare, what I’m working on, on deadlines, on life!

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

I wish it didn’t turn me into a crazy person, but it does. A pleasant surprise is just how kind so many people have been—withdrawing from the real world to write can be very isolating; it was lovely to emerge and be reminded of the community I write to be a part of.

5. What are you reading right now?

Right now I’m reading Honeyfish—an absolutely gorgeous collection of poetry by Lauren Alleyne, and the wonderful The Weil Conjectures—forthcoming!—about the siblings Simone and Andre Weil, by Karen Olsson. I’m in love with Christine H. Lee’s column Backyard Politics, which is about urban farming, family, trauma, love, resilience, growth—basically everything I care about. It’s been a very good few year of reading for me! I’m obsessed with Ali Smith and devoured her latest, Spring. I thought Women Talking by Miriam Toews and Trust Exercise by Susan Choi were both extraordinary. Helen Oyeyemi is one of my absolute favorites, and Gingerbread was pure brilliance and spicy delight. Jean Kwok’s recent release, Searching for Sylvie Lee, is a stunner; Mary Beth Keane’s Ask Again, Yes broke me with its tenderness and humanity; and Tea Obreht’s forthcoming Inland is magnificent. It took my breath away.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Ali Smith and Tove Jansson are both widely recognized, especially in their home countries—but I feel like they should be more widely read here than they are. I didn’t discover Smith until last year, and when I did it was like a hundred doors opening in my mind at once: She’s so playful and wise, she seems to know everything and can bring together ideas that seem completely unrelated until she connects them in surprising and beautiful ways, and her work is filled with such warmth and good humor. And Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book is so delicious, so sharp and clean and clear with the purity and wildness of nature and childhood. Ko Un is a Korean poet who’s well known in Korea, but not here—he’s incredible, his poems changed my idea of what poetry is and what it can do. I routinely e-mail his poems to people, just so they know. Bae Suah and Eun Heekyung are Korean fiction writers I admire—I really like reading work in translation because the conventions of storytelling are different everywhere, and I love being reminded of that, and being shown the ways my ideas of story can be exploded. Also, how Rita Zoey Chin’s memoir Let the Tornado Come isn’t a movie or TV show yet, I don’t know. Same with Dan Sheehan’s novel Restless Souls and Vaddey Ratner’s devastating In The Shadow of the Banyan. And Samantha Harvey is a beautiful, thoughtful, revelatory writer who I’m surprised isn’t more widely read in the States.

7. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started writing The Tenth Muse, what would say?

I’d say, “Hey, I know you’re worried about things like finishing and selling this book, and also health insurance and finding a job and not ending up on the street, and all that will more or less work out, but more pressingly, here I am from the future, freaking out because apparently I’ve figured out time travel and also either bypassed or am creating various temporal paradoxes by visiting you now. Clearly we have bigger issues than this book you’re working on or the current moment you’re in, so can you take a moment to help me figure some things out? Like how should I now divide my time between the present and the past? Am I obligated to try to change the outcome of various historical events? Should I visit the distant, distant past before there were people? Should I visit the immediate future? Do I even want to know what happens next and if I do will I become obsessed with trying to edit my life and history in the way that I edit my stories? Help!”

8. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

I don’t see it as a one-size-fits-all situation—I think sure, why not, if it’s fully funded and you feel like you’re getting something out of it. Otherwise, no. The key is to protect your own writing and trust your gut as far as what you want and need.

9. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

My mind, always my mind! Related: self-doubt, self-censorship, and shame.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Back in my twenties, when I was writing my first book, I was eating breakfast at the MacDowell Colony, and this older writer asked me where he could find my published work. I said nowhere. I had an essay coming out in a journal soon, but that was it. He was astonished that I’d been let in and made a big production out of my never having published before, offering to read my forthcoming essay and give me a grade on it. It was weird, but it also sort of bounced off me. Anyway, there was a British poet sitting next to me at that breakfast named Susan Wicks, and some days later, as I was going to fetch some wood (it was winter, we all had our own fireplaces and wood delivered to our porches—have I mentioned MacDowell is paradise?) I opened the side door to my porch, and a little letter fluttered to the ground. It was dated the day of the breakfast, and it was from Susan Wicks. It said: Dear Cathy, I was so angry at the conversation that happened at breakfast! If you are here, it is because you deserve to be here. And you should know there is nothing more precious than this moment of anonymity when no one is watching you. You will never have this freedom again. Enjoy it. Have fun! And have a nice day! And then she drew a smiley face and signed her name. Susan Wicks. I think of her and that advice and her kindness all the time.

Catherine Chung, author of The Tenth Muse. (Credit: David Noles)

Ten Questions for Mona Awad

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Mona Awad, whose new novel, Bunny, is published today by Viking. A riveting exploration of female relationships, desire, and the creative and destructive power of the imagination, Bunny is the story of Samantha Heather Mackey, an outsider in the MFA program at New England’s Warren University, a scholarship student who prefers the company of her own dark imagination. Repelled by the rest of her fiction writing cohort, who call one another “Bunny,” Samantha is nevertheless intrigued when she receives an invitation to the group’s fabled “Smut Salon” and she begins a descent into the Bunny cult and their ritualistic off-campus workshop, where the edges of reality start to blur. Mona Awad is the award-winning author of 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, a finalist for the Scotiabank Giller Prize. The recipient of an MFA in fiction from Brown University and a PhD in English and creative writing from the University of Denver, she has published work in Time, VICE, Electric Literature, McSweeney’s, Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere.

1. How long did it take you to write Bunny?

Two years. Three months to write the first draft and then a year and a half of revision

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Not giving up on it. I had a blast writing the first draft of Bunny and just let myself take risks and go down rabbit holes, but in the revision, I had to really reign it in and flesh it out. That took time. It didn’t help that every time I described the novel to someone, I burst out laughing because the story sounded so crazy to me. And then I’d panic. I’d think: what I’m writing is clearly insane. Pushing through that and continuing to embrace the madness of it was scary.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

When I’m working on a book, I try to write every morning for at least a few hours. I work in bed, at my desk or in the Writer’s Room of Boston. I’m pretty rigid about it, just because it really does help build momentum with the story and the voice to work on a story every day. Once I feel I’m emotionally inside the world of the story, I begin to work at night too. Towards the end, I work whenever I possibly can.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

Just how much people are interested in reality when we’re talking about fiction, in which parts of the story actually literally happened to you (the author). In some ways, I get it. Fiction is a reflection/refraction of reality, in some ways fiction is the ultimate form of memoir so it makes sense for people to be curious about how much of the writer’s actual life is mirrored in the story, but to me the most exciting things are always the things I make up. In my view, that’s the most telling stuff in the novel, not the stuff that literally maps to something that literally happened.

5. What are you reading right now?

Right now, I’m reading Tea Mutonji’s Shut Up, You’re Pretty and John Waters’s Mr. Know-It-All: The Tarnished Wisdom of a Filth Elder. I’m enjoying them both immensely.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Russell Hoban. I love the way he weaves the magical into the everyday and I love the way he writes loneliness. The Lion of Boaz-Jachin and Jachin-Boaz is a brilliant work of fabulist fiction, but it’s also a real meditation on the bond between a father and a son, and the desire for and cost of personal freedom. Turtle Diary is wonderful too. It’s just about two lonely people who decide to free a turtle at the London Zoo, but the characters are handled with such empathy, nuance and depth.

7. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started writing Bunny, what would say?

Trust yourself more.

8. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

Depends on the writer, the program and the project. I was very fortunate. My MFA was fully funded and when I started it, I was already halfway finished with my first novel, 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, which I completed there and turned into my MFA thesis. There was also a writer on the faculty, Brian Evenson, whom I admired deeply and was very keen to work with. So I knew exactly what I planned to do while I was there, I just needed time and space to work, and some guidance and encouragement from a community I could trust. I was also older—in my thirties—when I did it. So although I had lots of growing to do as a writer, I’d already found my voice, knew what I was going to work on and I’d lived a little. I think all of those factors contributed to why it was such a successful experience for me. It might not be the right thing for someone else and I don’t believe that you need it to write.

9. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Me. My own insecurities and impatience and shortcomings that show up when I write. Also my difficulty getting a routine going. My best work comes out of a sustained, daily practice of writing and sometimes that isn’t possible.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Write the shitty first draft. A finished story is better than a perfect story that just lives in your mind. And be curious. So much can come of being willing to shut up and pay close attention to the world around you.

Mona Awad, author of Bunny.

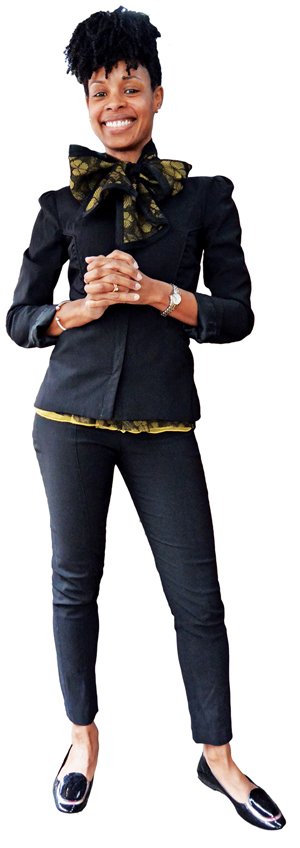

Ten Questions for Nicole Dennis-Benn

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Nicole Dennis-Benn, whose second novel, Patsy, is out today from Liveright, an imprint of W. W. Norton. The novel tells the story of two women, Patsy and her daughter, Tru. After leaving behind Tru for a life she’s always wanted in New York, Patsy ends up working as a nanny caring for wealthy children while Tru rebuilds a faltering relationship with her father back in Jamaica. Jumping back and forth between narratives in New York and Jamaica, Dennis-Benn has created “a stunningly powerful intergenerational novel,” as Alexander Chee writes, “about the price—the ransom really—women must pay to choose themselves, their lives, their value, their humanity.” Nicole Dennis-Benn is the author of Here Comes the Sun, a New York Times Notable Book and winner of the Lambda Literary Award. Born and raised in Kingston, Jamaica, she teaches at Princeton and lives with her wife in Brooklyn, New York.

1. How long did it take you to write Patsy?

For me, the process begins way before I put pen to paper. Patsy was conceived in the fall of 2012, when I started as an adjunct at the College of Staten Island. I was writing Here Comes the Sun at the time, but would scribble notes about my early morning travel on the subway and the Staten Island Ferry while commuting with other immigrants going to their various jobs. I began to wonder about these peoples’ lives—what versions of themselves they brought to America and what they left behind in their countries of origin. Here they were in America, hustling to get to their jobs on time, their heads bowed underneath vacation ads displaying white sand beaches in places some once called home. Struck by this irony, I began to write. The character of Patsy came to me and refused to leave, even through the publication of my first novel and well after. So, this book has been with me for seven years.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Writing the story of a woman, a mother who defies cultural and societal norms by abandoning her daughter in her quest for personal freedom, and by choosing to love the way she wants to love with her childhood best friend, Cicely. It took me some time to get comfortable with that angle of the story, but I realized early on that I couldn’t judge Patsy the way other people might. I had to be open to telling her story and portraying her as authentically as possible, knowing that there are women who grapple with this very same dilemma—feeling forced into motherhood by societal pressures, unable to live up to the high standards of the maternal role. Patsy didn’t have the opportunity to explore her own identity before becoming a mother. Her greatest desire is to find her place in the world, trying to define herself in a world that already defines her. Once I started to listen to that, I no longer found it challenging to step into her shoes and walk the miles with her.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Lately, I’ve been writing on the New Jersey Transit during my commute to Princeton, where I’ve been teaching this past year. But I mostly write in my study. Early morning and mid-afternoon are the perfect times for me. I try to write every day. If that isn’t possible—since we’re human and we need breathers—I read, watch television, and spend time with my loved ones. I find that the majority of my inspiration comes from just living my life, so I take my non-writing time as seriously as I do my writing.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

I was once that reader who devoured books without ever thinking about the process of how those books got to me in the first place. I didn’t know the sheer amount of work it took behind the scenes for a book to get on my bookshelf. I’m grateful for the team I have and for the opportunity to reach so many people.

5. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading Warsan Shire’s Teaching My Mother How to Give Birth. It’s one of the best poetry collections I’ve read in a while.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

There are so many authors who I think deserve wider recognition. There’s Sanderia Faye, author of Mourner’s Bench; Tracy Chiles McGhee, author of Melting the Blues; Mecca Jamilah Sullivan, author of Blue Talk and Love; JP Howard, an exceptional poet and author of Say Mirror; and Cheryl Boyce Taylor, who has written several collections of poetry, including my favorite, Arrival.

7. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started writing Patsy, what would say?

I would tell myself to relax, breathe, and trust the process.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

When I was first published, I used to read reviews on Goodreads and Amazon. But a very good mentor, who happens to be a renowned author, told me never to do that since reviews are really conversations between readers—that an author has no business being in that conversation unless she’s invited. That made perfect sense to me. Once I was able to block out that extra noise—both good and bad—I was able to completely focus on my next project.

9. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

That would be diversifying the gate keepers, not just in terms of race, but also class and culture. Expand the industry so that we have all different types of people of color; that there would be no such thing as a model minority of the year, but a celebration of everyone. Though I’ve been lucky to be surrounded and championed by people who understand me and get what I’m doing, deep down I question my belonging. I know that many writers of color who are in the game are anxious that the door might close soon—that our time might be up when the industry yawns and moves on to the next thing.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Elizabeth Strout once told me to keep my head down and write. That’s the greatest advice I’ve ever gotten. At the end of the day, we have to remind ourselves why we write and why it’s important for us to tell these stories. The universe will take care of the rest.

Nicole Dennis-Benn, author of the novel Patsy.

Ten Questions for Domenica Ruta

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Domenica Ruta, whose novel, Last Day, is out today from Spiegel & Grau. The fates of three sets of characters converge during the celebration of an ancient holiday anticipating the planet’s demise. A bookish wunderkind looks for love from a much older tattoo artist she met at last year’s Last Day BBQ; a young woman with a troubled past searches for her long-lost adoptive brother; three astronauts on the International Space Station contemplate their lives on Earth from afar. Last Day brings these characters and others together as they embark on a last-chance quest for redemption. Domenica Ruta is the author of the New York Times best-selling memoir With or Without You (Spiegel & Grau, 2013). A graduate of Oberlin College, Ruta received an MFA from the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas in Austin. Her short fiction has been published in the Boston Review, the Indiana Review, and Epoch. Her essays have appeared in Ninth Letter, New York magazine, and elsewhere. She reviews books for the New York Times, Oprah.com, and the American Scholar, and works as an editor, curator, and advocate for solo moms at ESME.com. She lives in New York City.

1. How long did it take you to write Last Day?

I started playing around with it immediately after my memoir, With or Without You, was published, but I was also writing another novel at the same time, trying to see which one would win my full attention. When I found out I was pregnant, I began pounding the keys of my laptop every day for a couple of hours to force out an ugly first draft before I became a single mother. In the first six months of my son’s life I wrote nothing. After that I worked a little at a time whenever I could, meaning whenever I could afford childcare. So the short answer is five years, but not continuously.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The most challenging thing for me as an author of this and probably any book I write is the way publishing is a performative act of maturation. Writers grow up in public. If you compare the first book written by your favorite author with one they wrote fifteen or twenty years later the difference in quality is almost always astounding. And this is the same human using the same tools. So it is challenging for me to let go of a work and set it free into the world when I am positive I could still make it better, if only I had a few more decades. But that’s what the next book is for, and the one after that.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write mostly in bed, with occasional commutes to my kitchen table. I try to write every week, sometimes every day, sometimes not. As a mother of a small child, there is no set schedule. I write when I can, usually when the kid is at school, and other pockets I can find.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

When my publisher and editor, Cindy Spiegel, lost her incredible imprint Spiegel & Grau after a banner year, just a few months before Last Day was published—this was not something I ever expected would happen.

5. What are you reading right now?

In Love with the World by Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche and Secrets We Kept by Kristal Sital.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Why doesn’t the Octavia Butler estate have ten different Netflix specials in the works right now?

7. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started writing Last Day, what would say?

I wish I had something that would create the mystique of myself as a precious artist, alchemist of verbs and nouns, thinker of Big Thoughts, but to be perfectly honest, if I could go back in time before this novel I would advise myself to get savvy about the whole social media game. It is so important for authors to market themselves and their work in this way, which I was totally oblivious to until very recently.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Self-doubt, self-hatred, self-sabotage; I love more than anything to be alone in my imagination, but sometimes it is a dangerous place.

9. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

Not unless it is fully funded. I cannot in good conscience recommend that anyone without a trust fund or wealthy no-strings-attached parents/patrons go into debt for a degree in the arts. Read every single interview in the Paris Review instead; you will learn there are as many different ways to write a book as there are writers. Read widely across genres and write terrible drafts of things you are ashamed of. But if an MFA program is fully funded, then definitely go. Being a professional student is the most fun job I’ve ever had.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Anne Lamott said something along the lines of “write a shitty first draft.” This is the only way I can summon the courage to write anything. I am human and flawed and this is never more evident than when I see it spelled out in my words on a screen or a sheet of paper. But as bad as that first draft may be—and sometimes it’s not as bad as my first impression of it is—I have a chance to make it better one day at a time. That is the craft. That is what makes a writer: the willingness to rewrite a thousand times if necessary.

Domenica Ruta, author of Last Day. (Credit: Charlie Mahoney)

Ten Questions for Sara Collins

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Sara Collins, whose debut novel, The Confessions of Frannie Langton, is out today from Harper. Both a suspenseful gothic mystery and a historical novel, Collins’s debut tells the story of a slave’s journey from a Jamaican plantation to an English prison, where she is tried for a brutal double murder she cannot remember. “With as much psychological savvy as righteous wrath, Sara Collins twists together slave narrative, bildungsroman, love story, and crime novel to make something new,” wrote Emma Donoghue. Sara Collins grew up in Grand Cayman. She studied law at the London School of Economics and worked as a lawyer for seventeen years before earning a master’s degree in creative writing at Cambridge University, where she was the recipient of the 2015 Michael Holroyd Prize for Creative Writing. She lives in London.

1. How long did it take you to write The Confessions of Frannie Langton?

My agent signed me with only a partial manuscript, and I had to write feverishly in order to finish it in just under two years. But the novel had been simmeringfor all the decades I’d spent wondering why a Black woman had never been the star of her own gothic romance. My dissatisfaction about that state of affairs grew so strong over time that it finally nudged me in the direction of writing my own.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

At times there was nothing more terrifying than the distance between the novel in my head and the one making its way onto the page. I had to force myself to accept the failure of my first attempts. I’m always terrified that the rough and rambling sentences that come out first, as a kind of advance party, will be all I can manage. They trick me into trying to polish them as I go. And that slows me down.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Either at my desk overlooking a quiet canal patrolled by iguanas in Grand Cayman or at my kitchen table in London overlooking my courtyard garden, and now sometimes in bed, to avoid the intense back pain I get after sitting for long periods. When working on a novel, I write every day, 8:00 AM to 7:00 PM, following very strict routines: starting and finishing at the same time, and aiming to get a certain quota of work done. Over time I’ve developed a Pavlovian response to my rituals: When I take the first sip of coffee at 8:00 AM, my brain flips a switch and I’m in writing mode.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

I wrote the novel in isolation, but I’ve now done numerous radio and podcast interviews, panel and bookshop appearances, essays and columns. Writing requires withdrawal, publishing demands engagement. It’s the shock of wandering out of a tunnel onto a stage.

5. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading Clarie Messud’s The Woman Upstairs. The writing feels electric and alive, crackling with anger, which I think we should have more of in novels. One of my top reads of recent months was André Aciman’s Call Me By Your Name. I’m going to start John Banville’s The Book of Evidence next.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

James Baldwin. He is unparalleled: as a writer, as an intellectual, as a man. Yes, he’s fairly widely recognized, but it should be wider.

7. What is one thing you’d do differently if you could have a do-over?

I would definitely take more days off.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

When I’m so immersed in a project that I don’t want to look up, let alone talk to anyone, I feel like I’m being pulled between novel and family. What many people won’t admit is that it’s impossible to write a novel without a pinch of selfishness, and you have to beg your loved ones to forgive you for it.

9. What trait do you most value in an editor (or agent)?

Each of my editors, and my agent, saw straight through my manuscript to the novel I wanted to write, not the one I’d written.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I often quote Annie Lamott quoting the coach in Cool Runnings (a film I dislike, but which apparently produced this great line): “If you weren’t enough before the gold medal, you won’t be enough afterwards.”

Sara Collins, author of The Confessions of Frannie Langton.

Ten Questions for Xuan Juliana Wang

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Xuan Juliana Wang, whose debut story collection, Home Remedies, is out today from Hogarth. In a dozen electrified stories, Wang captures the unheard voices of a new generation of Chinese youth via characters that are navigating their cultural heritage and the chaos and uncertainty of contemporary life, from a pair of synchronized divers at the Beijing Olympics on the verge of self-discovery to a young student in Paris who discovers the life-changing possibilities of a new wardrobe. As Justin Torres writes, Wang “is singing an incredibly complex song of hybridity and heart.” Xuan Juliana Wang was born in Heilongjiang, China, and grew up in Los Angeles. She was a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University and earned her MFA from Columbia University. She has received fellowships and awards from Yaddo, the MacDowell Colony, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, Cite des Arts International, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, New York Foundation for the Arts, and the Elizabeth George Foundation. She is a fiction editor at Fence and teaches at UCLA.

1. How long did it take you to write the stories in Home Remedies?

All of my twenties and the early part of my thirties.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I would have to say the loneliness of falling out of step with society. When I’m out celebrating a friend who has just made a huge stride in their career, someone would ask me, “Hey how’s that book coming along?” Then having to tell them that I have a desk in an ex-FBI warehouse and I’ll be sitting there in the foreseeable future, occasionally looking out the window, trying to make imaginary people behave themselves.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I keep a regular journal where I describe interesting things I’d seen or heard the day before as well as random plot ideas. That’s something I like to do every day, preferably first thing in the morning or right before bed. My ideal writing environment is a semi-public place, like a shared office, or a library as long as I can avoid making eye-contact with people around me. When I’m really getting going on an idea I am capable of sitting for eight hours a day, many days in a row. I was forced to play piano as a child so I have no trouble forcing myself to do anything.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

It made me feel a deep kinship with anyone who has ever published a book. I want to clutch them, look into their eyes and say, “I understand now.”

5. What are you reading right now?

King of the Mississippi by Mike Freedman. I just picked up Heads of the Colored People by Nafissa Thompson-Spires and it’s great! I’m putting off finishing The Unpassing by Chia Chia Lin because it’s so gorgeously written I am savoring it.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Wang Shuo. He’s like the Chinese Chuck Palahniuk. I wish he could be translated more and better.

7. What is one thing you’d change about the literary community and/or the publishing business?

I wish publishers would open up their own bookstores, or sell books in unexpected places, so people could interact with books in-person. There isn’t a single bookstore within a fifteen-mile radius of the city where I grew up in LA.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Health insurance.

9. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

Yes. But choose wisely.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Victor Lavalle gave us a lot of practical advice in his workshop. The one I use the most often is: Take the best part of your story and move it to first page and start there. Challenge yourself to make the rest rise to the level of that.

Xuan Juliana Wang, author of the story collection Home Remedies. (Credit: Ye Rin Mok)

Ten Questions for Julie Orringer

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Julie Orringer, whose third book, the novel The Flight Portfolio, is out today from Knopf. Based on the true story of Varian Fry, a young New York journalist and editor who in 1940 was the head of the Emergency Rescue Committee, designed to protect artists and writers from being deported to Nazi concentration camps and to send intellectual treasures back to the United States, The Flight Portfolio returns to the same territory, Europe on the brink of World War II, that thrilled readers of Orringer’s debut novel, The Invisible Bridge. Andrew Sean Greer calls it “ambitious, meticulous, big-hearted, gorgeous, historical, suspenseful, everything you want a novel to be.” Orringer is also the author of the award-winning short story collection How to Breathe Underwater, which was a New York Times Notable Book. She lives in Brooklyn.

1. How long did it take you to write The Flight Portfolio?

Nine years, more or less. While researching my last novel, The Invisible Bridge, which also took place during the Second World War, I read about the American journalist Varian Fry’s heroic work in Marseille: His mission was to locate celebrated European artists who’d fled to France from the Nazi-occupied countries and arrange their safe passage to the States. The job was fraught with moral complications—given limited time and resources, who would Fry choose to save?—and the historical account seemed to miss certain essential elements, particularly those surrounding Fry’s personal life (he had a number of well-documented relationships with men, a fact that historians elided, denied, or shuddered away from, as if to suggest that it’s not acceptable to be a hero of the Holocaust if one also happens to be gay). Researching Fry’s life and mission took the better part of four years—a time during which I moved three times and gave birth to my two children—and writing and revision occupied the five years that followed. Which is not to suggest that no writing occurred during the initial research, nor that there was ever a time when the research ceased—it continued, in fact, through the last day I could change a word of the draft.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Undoubtedly it was the research into Fry’s work in Marseille, a detailed record of which exists in biographies, interviews, letters, ephemera, and even still in living memory: Fry’s last surviving associate, Justus Rosenberg, is a professor emeritus of languages and literature at Bard College, and was kind enough to speak to me about his experiences. Twenty-seven boxes of Fry’s letters, papers, photographs, and other writings reside in the Rare Books and Manuscripts collection at Columbia’s Butler Library; I spent many hours immersed in those files, learning what I could about what kept Fry up at night, what obsessed him by day, what he struggled with, how he triumphed, and how he thought about his own work years later. I spent a year at the Radcliffe Institute at Harvard, where Fry studied as an undergraduate; there I had the chance to examine his recently unsealed student records, which include not only his grade transcripts and his application, but also letters from his father, his professors, the dean, and various close associates, many of them arguing either for or against Fry’s expulsion from Harvard for a variety of infractions that included spotty attendance, raucous partying, destruction of school property, reckless driving, and, ultimately, the placing of a For Sale sign on Dean Greenough’s lawn. Then there were the dozens—hundreds, ultimately thousands—of Fry’s clients, whose lives and work I felt I must know before I wrote the book. And of course I had to go to Marseille, where I visited the places Fry lived and worked, at least those that still exist (the marvelous Villa Air Bel, where he lived with a group of Surrealist writers and artists, was razed decades ago). The nearly impossible task was to clear space among all that was known for what could not be known—space where I could make a narrative that would honor Fry’s experience but would move beyond what could have been recorded at the time.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write five or six days a week at the Brooklyn Writers’ Space. I’m married to another fiction writer, my former Iowa MFA classmate Ryan Harty, and, as I mentioned, we have two young children; we have a carefully worked-out schedule that allows each of us a couple of long writing days each week (eight hours or so) and a number of shorter ones (five hours). Often I write at night, too, especially if I’m starting something new or working on a short story or a nonfiction piece.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

The inestimable benefit of sharing a very early draft with my editor, Jordan Pavlin. Jordan edited my two previous books, but I’d never before shown her anything that hadn’t been revised six or seven times. This novel involved so much risk, and took so long to complete, that I felt I needed her insight and support long before I’d written three or four versions. Did the novel strike the right balance between history and fiction? Had I captured the characters’ essential struggles clearly? How to address problems of pacing, continuity, clarity? Jordan’s exacting readings—not just one, but three or four—echoed my own doubts and provided necessary perspective and reassurance. And her comments pulled no punches. She was scrupulously honest. She was rigorous. She challenged me to do better. And my desire to meet her standards was, as it always is, fueled as much by my ardent admiration for her as a human being as by my deep respect for her literary mind.

5. What trait do you most value in an editor?

See above.

6. What are you reading right now?

Susan Choi’s Trust Exercise, which cuts a little too close at times to my own 1980’s experience in a high school drama group—one that took itself at least as seriously as Choi’s Citywide Academy for the Performing Arts. She hits all the notes with dead-on precision: favoritism toward certain students by charismatic teachers, intrigue surrounding highly-charged relationships, endless quoting of Monty Python, jobs at TCBY, the dire importance of having a car and/or friends with cars, etc. But the true brilliance of the book is its structure: A first section in which the subjective experience of high school students is rendered with respect and utter seriousness; a second section that brings a questioning (and revenge-seeking) adult sensibility to bear upon the first; and a third section that sharpens the earlier sections into clearer resolution still, suggesting the persistent consequences of those seemingly trivial sophomore liaisons.

7. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Here are three new writers whose work I’ve found risk-laced, challenging, and full of fierce delights: Ebony Flowers, Rona Jaffe-winning cartoonist and disciple of Lynda Barry, whose brilliant debut short story collection, Hot Comb, will be published by Drawn and Quarterly in June; shot through with tender and intelligent humor, it’s an incisive examination of cultural and familial tensions in black women’s lives. Domenica Phetteplace is another of my favorite new writers; her marvelous short story “Blue Cup,” a futurist skewering of commerce-driven life in the Bay Area, involves a young woman whose job requires her to deliver tailored social experiences to clients at an exclusive dining club; the story is narrated by the artificial intelligence software that co-inhabits her mind. And Anjali Sachdeva’sAll the Names they Used for God is a story collection that merges the real and the supernatural with genre-breaking bravery, employing a prose so precise that you follow her into marvelous realms without question: Ice caves, exploding steel mill furnaces, an ocean inhabited by an elusive mermaid whose fleshy, tentacle-like hair still haunts my dreams.

8. What is one thing you’d change about the literary community and/or the publishing business?

I’d love to see more works in translation published in this country—for more publishing houses to commit seriously to the cultivation and dissemination of international literature. I admire the work of New York Review Books, Restless Books, and Europa Editions in this arena. I loved, for example, Restless Books’ recently published translation of Marcus Malte’s The Boy, a Prix Femina-winning novel about a young man who spent the first fourteen years of his life in mute isolation in the wilds of France. The story of this young man’s entry into the early twentieth-century world—first into a rural setting, then Paris, and finally the battlefields of the First World War—is the story of what makes us human, and casts our world in a stark new light. Even stories as place-specific as The Boy have much to reveal about all our lives; and, just as importantly, they illuminate and particularize the vast array of human experiences different from our own. One of literature’s great powers is its ability to act as a tonic against xenophobia; there’s never been a moment when that power has been more urgently needed.

9. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

The finite nature of the twenty-four-hour day. But places like the MacDowell Colony and Yaddo, the New York Public Library’s Cullman Center and the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, seek to explode that limitation by removing barriers to creative freedom. At MacDowell, where every artist gets a secluded studio, meticulously prepared meals, and unlimited uninterrupted time to work, there’s a kind of magical speeding-up of the creative process. You don’t necessarily fail less often; you fail faster, and recover faster. The people who dedicate their professional lives to the running of those programs are literature’s great guardians and cultivators.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

It would be impossible to identify the best, because I’ve been the fortunate recipient of much wonderful advice from writers like Marilynne Robinson, James Alan MacPherson, Tobias Wolff, Elizabeth Tallent, and John L’Heureux, for more years than I care to consider. But I can tell you about a piece of advice I chose not to take: A prominent writer once told me, at a barbecue at a friend’s house in Maine, that if I wanted to take myself seriously as a writer, I’d better reconsider my desire to have children. For each child I had, this writer told me, I was sacrificing a book. Now I can say with certainty that my writing life has been immeasurably enriched and transformed by having become a parent. And if parenthood is demanding, both of time and emotional energy—as of course it is—life with children reminds me always of why writing feels essential: At its best and most rigorous, it illuminates—both for writer and reader—the richness and complexity of the human world, and forces us to make a deep moral consideration of our role in it.

Julie Orringer, author of The Flight Portfolio. (Credit: Brigitte Lacombe)

Ten Questions for Namwali Serpell

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Namwali Serpell, whose novel The Old Drift is out today from Hogarth. Blending historical fiction, fairy-tale fables, romance, and science fiction, The Old Drift tells a sweeping tale of Zambia, a small African country, as it comes into being, following the trials and tribulations of its people, whose stories are told by a mysterious swarm-like chorus that calls itself man’s greatest nemesis. In the words of Chinelo Okparanta, it is a “dazzling genre-bender of a novel, an astonishingly historical and futuristic feat.” Namwali Serpell teaches at the University of California in Berkeley. She won the 2015 Caine Prize for African Writing for her story “The Sack.” She received a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award for women writers in 2011 and was selected for the Africa39, a 2014 Hay Festival project to indentify the best African writers under the age of forty. Her fiction and nonfiction has appeared in the New Yorker, McSweeney’s, the Believer, Tin House, Triple Canopy, Callaloo, n+1, Cabinet, the San Francisco Chronicle, the Guardian, and the New York Review of Books.

1. How long did it take you to write The Old Drift?

I’ve been writing it off and on since the year 2000. I worked on it in between getting my PhD; publishing my first work of literary criticism, a dozen stories, and a few essays and reviews; getting tenure; and writing a novel that went in a drawer. I concentrated exclusively on The Old Drift after I sold it based on a partial manuscript—about a third—in 2015. I finished in 2017.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Fact-checking. The novel is rife with speculative fiction—fairy tale, magical realism, science fiction—but I was anxious to get historical, scientific, and cultural details right, that the notes didn’t sound off. Because the novel is so sprawling, it was hard to verify everything. I’m grateful for my informants—family, friends, acquaintances, strangers, and the blessed internet.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I’m too nomadic, or “movious” as we say in Zambia, to limit myself to a particular desk in a specific nook with a certain slant of light. I write from late morning to late afternoon, when most people are hungry or sleepy—I seem to find both states conducive to “flow,” as they call it. My writing frequency varies by genre. I can write nonfiction or scholarly prose for about five hours at a time, and as many days in a row as needed. I can write fiction for about three hours at a time, and it improves distinctly if I write every other day. My best work, regardless of genre, often happens in one big burst—an eight hour stretch, say, like a fugue. But I can’t prime my schedule or prepare myself for those eruptions. They come as they wish. I am left spent and grateful.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

The chasm between writing the book and marketing the book. It’s a rift in one’s psychology but also in logistics (who does what), and most shockingly, in value. There is simply no calculable relation between these two value systems: the literary and the financial, the good and the goods.

5. What are you reading right now?

Maurice Carlos Ruffin’s We Cast a Shadow. I’m excited because it draws on a longstanding preoccupation of mine: the recurrent fantasy of racial transformation in sci-fi.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

María Luisa Bombal.

7. What is one thing you’d change about the literary community and/or the publishing business?

Blurbs. They tap into our most craven, gratuitous, and back-patting tendencies. End them.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

The problem of money, of course.

9. What trait do you most value in an editor (or agent)?

Being able to recognize how things will best coincide—opportunities, ideas, words, people—and not forcing them, but setting up the space for them to do so. It goes by various names: “finger on the pulse,” “a sense of the zeitgest,” “savvy.” I think of it as a feel for kismet.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Amitav Ghosh once visited a graduate course I was taking. And he said of a writer (who shall remain nameless): “If everything is a jewel, nothing shines.”

Namwali Serpell, author of The Old Drift. (Credit: Peg Skorpinski)

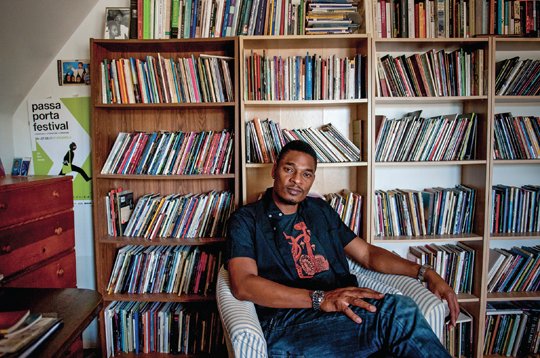

Ten Questions for Bryan Washington

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Bryan Washington, whose debut story collection, Lot, is out today from Riverhead Books. Set in Houston, the stories in Lot spring from the life a young man, the son of a Black mother and a Latino father, who works at his family’s restaurant while navigating his relationships with his brother and sister and discovering his own sexual identity. Washington then widens his lens to explore the lives of others who live in the myriad neighborhoods of Houston, offering insight into what makes a community, a family, and a life. “Lot is the confession of a neighborhood,” writes Mat Johnson, “channeled through a literary prodigy.” Bryan Washington’s stories and essays have appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times, BuzzFeed, Vulture, the Paris Review, Tin House, One Story, Bon Appetité, American Short Fiction, GQ, Fader, the Awl, and elsewhere. He lives in Houston.

1. How long did it take you to write the stories in Lot?

Three years-ish.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Description is always tricky for me, and that held up in every story.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I can edit wherever, but I prefer to write new stuff in the mornings. And I write most days, if I’ve got a project going. But if I don’t then I won’t.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

Hearing back from folks about the galleys was really rad.

5. What are you reading right now?

Xuan Juliana Wang’s Home Remedies, Morgan Parker’s Magical Negro, Pitchaya Sidbanthad’s It Rains in Bangkok, Candice Carty-Williams’s Queenie, and Yuko Tsushima’s Territory of Light. Then there’s Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We Were Briefly Gorgeous, which is probably going to change everything.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

More folks in the States should know about Gengoroh Tagame and My Brother’s Husband.

7. What is one thing you’d change about the literary community and/or the publishing business?

It’d be nice if the American literary community’s obsession with signal-boosting the optics of diversity were solidified into a tangible, fiscally remunerative reality for minority writers.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Living.

9. Would you recommend writers attend a writing program?

If you can go for free? Sure. But there are other ways.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Mat Johnson taught me a lot, and one of the most profound things he said was to just relax. Readers can sense when you’re tense.

Bryan Washington, author of Lot. (Credit: David Gracia)

Ten Questions for Ed Pavlić

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Ed Pavlić, whose novel Another Kind of Madness is out today from Milkweed Editions. The epic story of Ndiya Grayson, a young professional with a high-end job in a Chicago law-office who meets Shame Luther, a no-nonsense construction worker who plays jazz piano at night, Another Kind of Madness moves from Chicago’s South Side to the coast of Kenya as the pair navigate their pasts as well as their uncertain future. Of the novel Jeffrey Renard Allen writes, “In these pages, Black music sounds and surrounds experience like a mysterious house people long to live in but can’t find, a quest where they find themselves ever more deeply involved.” Widely published as a poet and scholar, Ed Pavlić is the author of the collection Visiting Hours at the Color Line, winner of the 2013 National Poetry Series, as well as ‘Who Can Afford to Improvise?’: James Baldwin and Black Music, the Lyric and the Listeners and Crossroads Modernism: Descent and Emergence in African American Literary Culture.

1. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I’ve always written in and around the gifts and demands of family, parenting, etc. I have no real literary credits that pre-date my life as a father and husband. In fact, often I’ve worked while pretty confused about which aspects of all of that were “gifts” and which were “demands,” demanding gifts in any case. I’ve also written in and around the work as a professor and administrator in universities. For many years I found I could compose and revise poems in the momentary midst of all of that overlapping life and labor. Most likely poems were the way I survived those overloads, kept track of enough of the mind and body, all those minds and bodies, so that I didn’t go permanently off the rails. So I could at least find my way back to the tracks when wrecks and crack-ups did—and they did, of course—occur.

Maybe writing was and is a way to address the displacements of an upwardly mobile, cross-racially identified, working-class man amid waves and undertows in an intensely segregated, hyper-racialized, and hierarchical bureaucratic world. Or maybe, for a working class consciousness like mine, writing is just another wave of displacement? Most likely it’s both. I guess we could file most of these thoughts under the “where” I write part of the question.

2. You write both poetry and prose; does your process differ for each form?

Essays and other longer works weren’t as immediately about or out of that tumble of pleasure and trouble, of placement, displacement and replacement, of the startling novelty and bone-bending drudgery of, say, early parenthood, or of showing up to work in the unbelievably bourgeois and indelibly white halls of academia. At least that work wasn’t doused in the texture of my tumbles and pleasures in the same way. So, I’ve written what might pass as prose, and lots of it, in times when I can work for extended periods, on days—at times weeks or even months—when I don’t have to totally leave that space tomorrow, where I didn’t arrive fresh to it today. So, if I’ve got four days “off” from the rest of the work-world, I can work away at what’s called prose on the middle days.

3. How long did it take you to write Another Kind of Madness?

I wrote Another Kind of Madness in a way unlike anything else I’d ever written, or done. I worked on the novel only in spaces where I had at least a month in which I could be with the work unencumbered by the demands of life and employment. I began it in the summer of 2009 when the kids were old enough (and my in-laws young enough) that they could be with the grandparents in Maryland for six weeks during the summer. Stacey went to work and I turned the front porch in Georgia into a writing retreat. Working “at home” in this way was something I’d almost never done. After that summer, I worked on the book in similar breaks of a month or two, but never again at home. Instead, I worked in rented, borrowed, or gifted spaces in Montreal, at the MacDowell Colony (twice), in Istanbul, in Mombasa, and in Lamu Town on the coast of Kenya, in France, and in the West Farms section of the Bronx, a few blocks south of the Bronx Zoo one summer.

During these strange times I floated by myself in mostly urban, unfamiliar spaces, writing a few hours a day and then spending the rest of the days and nights accompanied by the story on walks, at meals, in dreams, on errands, in reading books I found in those places, etc. I found that the story wouldn’t reveal itself amid the tumble of my life, would only appear when I could really sit, walk, and sleep with it, where it could accrue its reality in a textured and present—but also most often in a peripheral and angular—region of my attention. The pressure of my daily worlds seemed to obliterate that nimble angularity, but my comings and goings in those unfamiliar urban spaces allowed this story to happen. I remember showing up after eight months away from the book, opening a blank, unlined (yes, unlined: “free your lines, the mind will follow”) notebook and waiting for Shame, Ndiya, Junior, Colleen and them to let me know what had been happening since we last saw each other and, in return, I tried to be as honest with them as I could be about what had been happening with me. It was always as if, unknowingly, we had, in fictional-fact, been at some of the same parties.

4. What has been the most surprising thing about the publication process?

That it takes a village.